Late Thursday morning, when the National Park Service began restoring the panels commemorating nine people enslaved by George Washington at the President’s House at Sixth and Market, it should’ve been a time of jubilation.

Instead, it left many activists waiting for the other shoe to drop.

The National Park Service, which removed the panels from the site in late January to comply with an executive order by President Donald Trump, was successfully sued by Mayor Cherelle L. Parker’s administration. U.S. District Judge Cynthia Rufe ordered the NPS to restore the display, but the agency appealed.

So yes, the federal government complied with the judge’s order, but only for the moment.

Friday morning, Judge Rufe denied the government’s motion for an emergency stay of the order, but the Trump administration’s appeal is ongoing, thus continuing the fight to remove the panels for good.

It was yet another dramatic turn in a month in which I’ve lived the joys and pains of Black history.

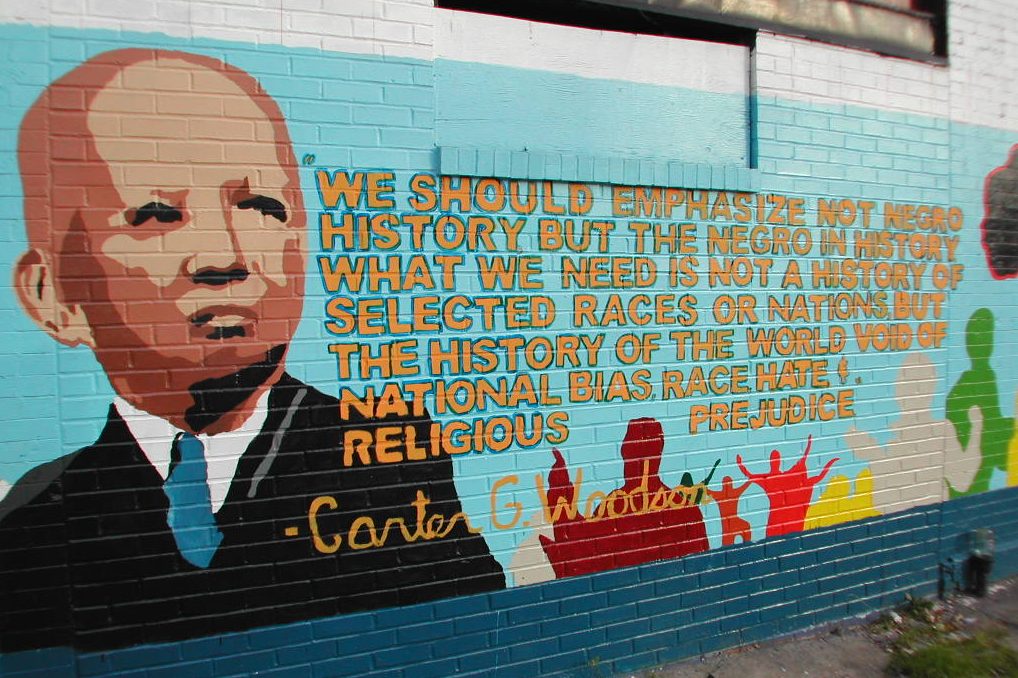

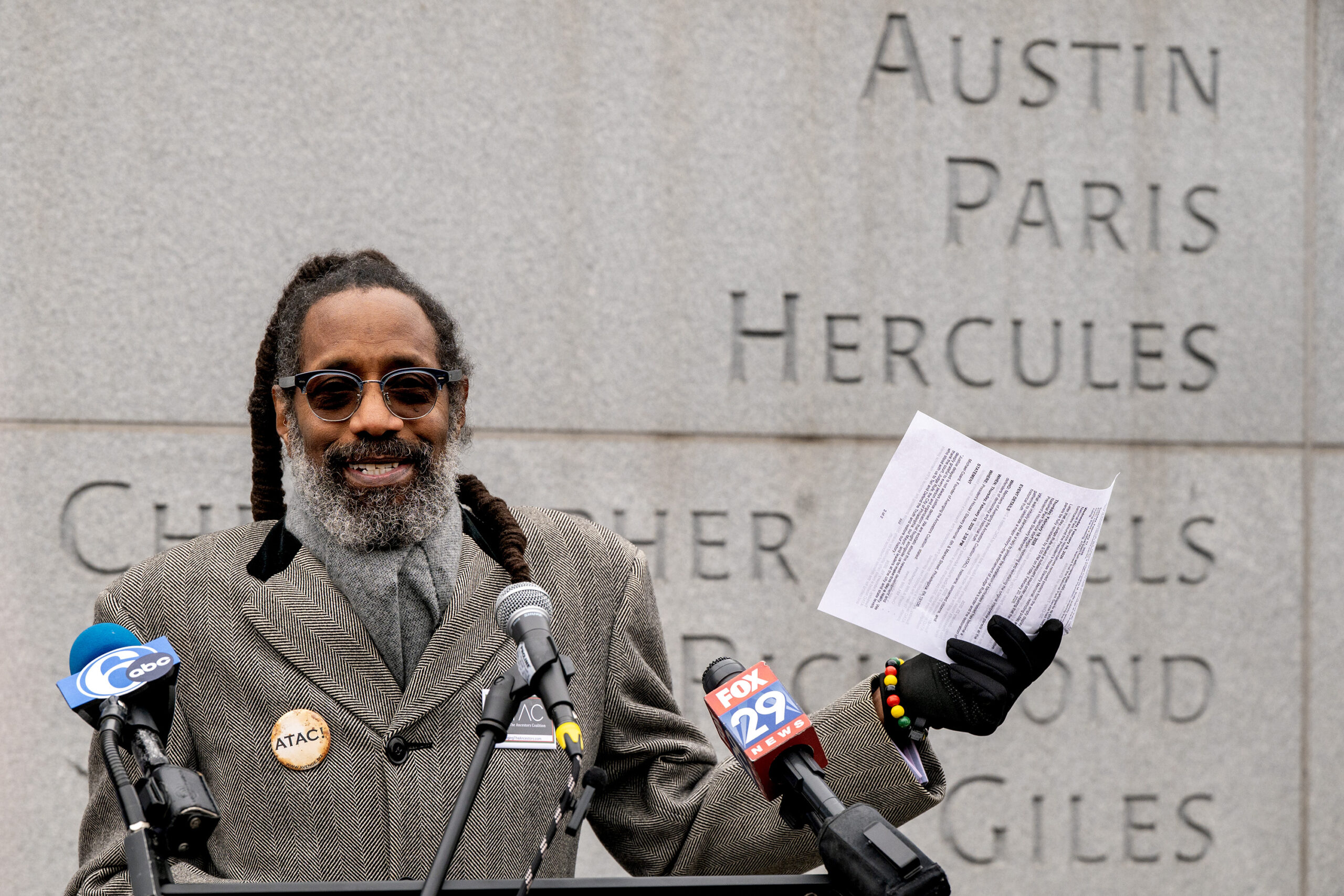

I was there when Judge Rufe took lawyers into the National Constitution Center to inspect the materials the Trump administration pried from the walls with crowbars. I spoke at a rally where the Avenging the Ancestors Coalition (ATAC) demanded the restoration of the slavery memorial. I listened as ATAC founder Michael Coard announced that Judge Rufe had ordered the panels to be restored.

Like so many in Philadelphia, I have watched the fight for the President’s House unite people of all stripes. I’ve experienced the emotional victories and defeats.

But even with the restoration of the panels, we are all left teetering on the razor-thin edge that separates celebration from grief, and elation from rage. We cannot stay there. We must continue to fight for the truth.

In Philadelphia, a city that frequently hosted civil rights leader Jesse Jackson, who died this week after a life spent fighting for justice, we fight.

Here, in the place where the story of enslavement lived side by side with the struggle for freedom, we fight.

Here, in a place where a new generation of combatants joins a centuries-old battle for the truth, we fight.

More rallies will come, and in the shadow of Independence Hall, where wealthy white men declared their own freedom while withholding liberty from my ancestors, a new American Revolution will take shape from the same war of ideas Jackson fought. It will be based on the rhetoric of America’s founders.

If indeed all men are created equal, our history should be equally told. That idea cannot be contained by metal barriers. We’ll see if it can be enforced in the courts.

Still, truth is not about legalities or displays.

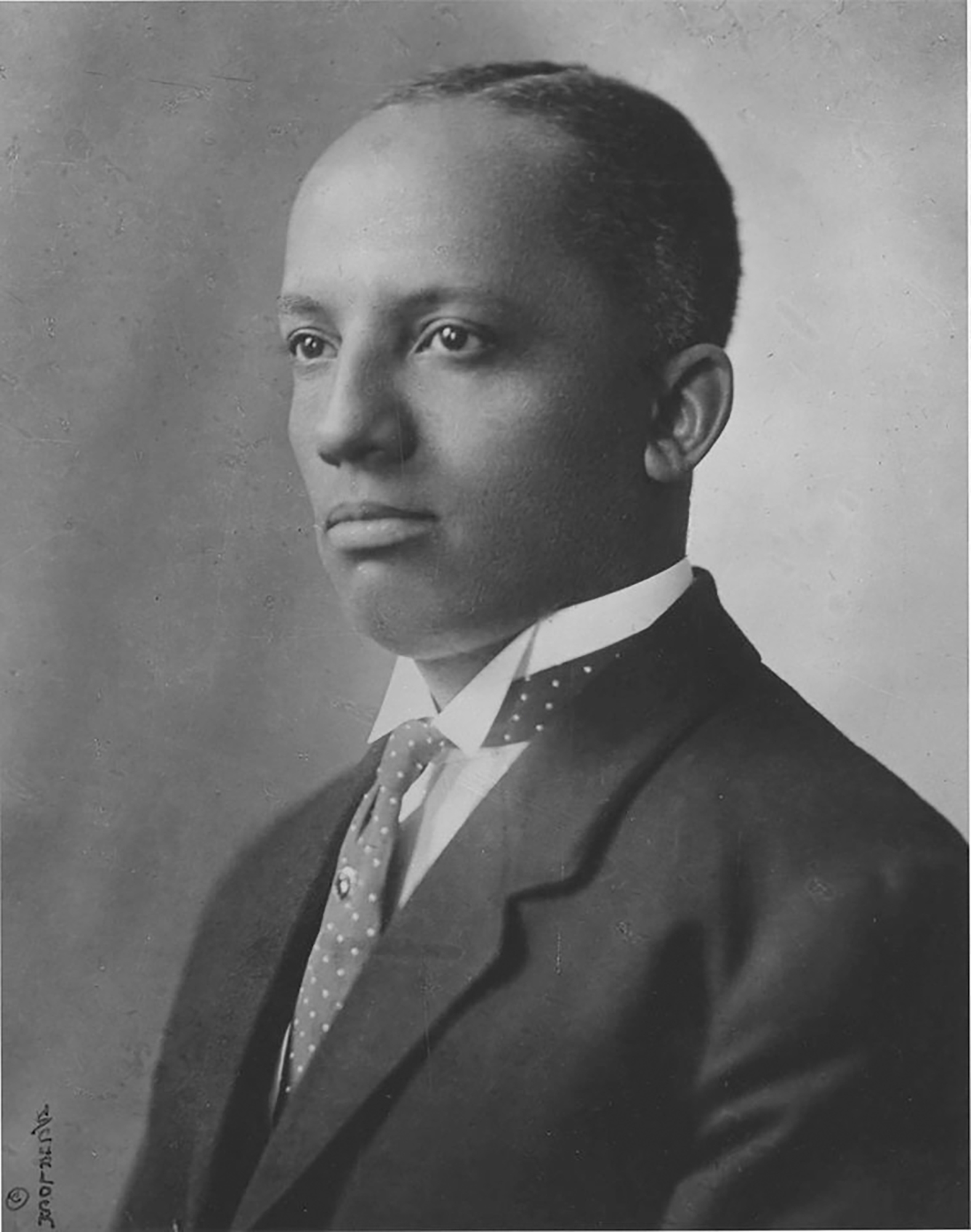

The truth of slavery in Philadelphia exists in the names of our neighborhoods, our streets, and even our schools. It exists in the very fabric of who we are.

The neighborhood of Logan is named for James Logan, who served as secretary to William Penn. He also enslaved people.

Chew Avenue is named for the Chew family, who lived in an estate called Cliveden, which is also the name of a street. The Chews enslaved people at Cliveden.

Front and Market, home to the London Coffee House, once hosted a market of a different kind. People were sold there. It was a key element of the business of slavery.

Girard Avenue is named for Stephen Girard. He was a very rich man with a very complicated legacy, and yes, he was also an enslaver.

Perhaps that’s why I was so angry when I went to the President’s House in the days after the Trump administration pried truth from the walls.

It was almost like someone had taken something that belonged to me, and in truth, they did. They took my history, but as I stood in that barren space on a cold afternoon, it was as if my ancestors were all around me — like the great cloud of witnesses from Scripture — telling me all they had endured.

Perhaps the Trump administration will ultimately achieve its goal and remove the panels from the site. Or maybe the truth will prevail.

But our fight is about more than the nine people Washington enslaved. This is about all of us, and it will take all of us to win.