Raymond and Anna Wakeman had returned from dinner early on a Saturday night and were relaxing on the couch with their two rescue dogs in their Northeast Philadelphia home. Cricket, a pit bull, rested his head on Raymond’s shoulder. Jax, a miniature pinscher, was curled up next to Anna.

In an instant, a 2014 Dodge Dart exploded through the front of the Wakemans’ home and into their living room.

Firefighters arrived to find Anna in another room, pinned under the silver Dodge and gravely injured. Rescuers worked feverishly to free her from the wreckage and rush her to the hospital. Jax was dead. Cricket underwent emergency surgery, but died soon after.

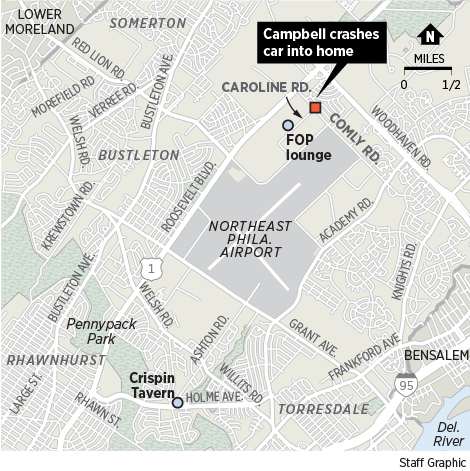

The driver, off-duty Philadelphia Police Officer Gregory Campbell, had been drinking since midafternoon on Feb. 6, 2021, and a lawsuit would later allege he had consumed as many as 20 alcoholic beverages. He had most of them where he ended his evening, at the 7C Lounge, a members-only club for active and retired cops operated by the Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 5, inside the union’s headquarters.

Campbell was arrested and fired from the police force after the crash. In June 2022, a Common Pleas Court judge sentenced him to 11½ to 23 months in prison.

“I am so sorry,” Campbell told the Wakemans in court, “for everything I’ve put you and your family through.”

Campbell’s accident and subsequent trial were widely covered at the time. But an Inquirer investigation has found troubling new details about that crash and the aftermath that were never made public, and identified two additional auto accidents tied to the 7C Lounge. The findings raise questions about how drunken-driving cases are investigated when they involve a powerful police union operating its own bar.

Records show that after crashing into the Wakeman house — and while it was still unclear whether Anna Wakeman had survived — Campbell was allowed to confer with FOP representatives and delay a blood-alcohol test for nearly six hours.

The delay was an apparent violation of Pennsylvania law, which requires suspected drunk drivers to undergo testing within two hours of being behind the wheel unless good cause is given. The records include no explanation for the delay.

An officer in the police department’s Crash Investigation District later testified in a deposition that he had never before encountered a person accused of driving under the influence who was allowed to seek guidance from his labor union before undergoing blood testing.

When Campbell’s blood was finally tested, his alcohol level registered at 0.23%, almost three times the 0.08 legal threshold for drunken driving. A toxicologist later estimated Campbell’s blood-alcohol content at the time of the accident was as high as 0.351%, more than four times the legal limit.

The Wakemans filed a lawsuit in Philadelphia Common Pleas Court against Campbell, the 7C Lounge, and Lodge 5. The couple’s attorney hired a liquor liability expert — a former police officer who had been an investigator for the New Jersey Division of Alcoholic Beverage Control for 11 years — who concluded that there was “overwhelming evidence” that the 7C Lounge had overserved Campbell and failed to monitor him or intervene.

The “actions and inactions were negligent and reckless” and “contributed directly to the accident, damages and injuries sustained by the Wakeman family,” the expert, Donald J. Simonini, wrote in his 23-page report.

On the night of the crash, a Philadelphia police accident investigator attempted to interview employees working at the 7C Lounge but was unable to do so because the bar had closed hours earlier than scheduled. The investigator said subsequent attempts to obtain information from the employees were also unsuccessful.

A manager later testified that he was “following orders” when he shut down the bar early.

At that time, Lodge 5 was led by its longtime president, John McNesby. His chief of staff, Roosevelt Poplar, was vice president of the union’s Home Association, a nonprofit that operates the 7C Lounge.

McNesby resigned in 2023, and was succeeded by Poplar, who last year won a contentious reelection battle.

Neither McNesby nor Poplar responded to requests for comment.

State law grants regulators broad authority to crack down on bars found to have overserved customers, with sanctions ranging from fines to suspension or revocation of a liquor license. Yet the FOP’s bar has faced no regulatory repercussions during the 16 years it has operated at its Northeast Philadelphia headquarters.

Paul Herron, a Philadelphia lawyer who specializes in liquor licenses and enforcement, said that the Pennsylvania State Police Bureau of Liquor Control Enforcement (BLCE) has “very stringent requirements” and that most establishments tend to have at least minor violations, such as improper recordkeeping. He said it is “very unusual” that the 7C Lounge has a clean slate given the severity of the Campbell case.

Campbell “had consumed monumental amounts of liquor, and for that to just not show up anywhere is awfully strange,” Herron said. “I would expect that if this happened to another place, that this would come to light, to the knowledge of the bureau, and they would ultimately issue a citation.”

In another incident tied to the 7C Lounge, regulators did not open an investigation because the union did not report what had happened.

The Inquirer viewed two minutes and 40 seconds of surveillance footage of the 7C Lounge parking lot from the evening of Nov. 22, 2021. The recordings come from three separate cameras and show a patron walking out of the 7C Lounge and getting into the driver’s seat of a compact SUV. At 11:21 p.m., the driver backs up, then accelerates forward into a parked truck, hitting it hard enough to slam the truck into the front bumper of an SUV parked behind it.

The motorist pauses a few seconds, reverses, then accelerates past the damaged vehicles and runs over two orange cones. The driver then plows through the FOP’s fence on Caroline Road, destroying a section of it, before disappearing from the camera’s view.

A source with firsthand knowledge of the incident said Poplar reviewed the footage of the parking lot crashes and took notes, including “4 cars hit” and “fence,” with the time each object was hit.

A police spokesperson said there is no record that the crashes in the 7C Lounge parking lot had ever been reported to authorities.

Herron said a typical bar would have almost certainly reported that type of incident.

“It’s just not something that would have happened maybe if it didn’t involve the police or the FOP,” he said.

‘I was dizzy’

There are potential conflicts of interest if law enforcement officers with arresting powers own establishments that serve alcohol. In fact, state law prohibits police officers from holding liquor licenses because they are responsible for enforcing liquor laws.

But that restriction does not extend to the FOP’s Home Association because it is considered part of a fraternal, nonprofit organization. State law defines such entities as “catering clubs” — much like a VFW post or an Elks Lodge — and permits them liquor licenses.

It’s a loophole in the law that Anna Wakeman, who barely survived the accident with Campbell’s Dodge, doesn’t understand.

“The cops can drink as much as they want there,” Wakeman, now 58, said. “The bartenders serve them till they’re blackout drunk and let them leave.”

When Campbell crashed into the Wakemans’ home, it was the second time the family’s property had been damaged by a patron who left the FOP’s bar impaired. Less than two years earlier, a former Philly cop had left the 7C Lounge, got into his car, and smashed into Anna Wakeman’s SUV, which was parked in her driveway.

On a Sunday night in April 2019, an ex-Philly cop named Damien Walto worked as a DJ at the 7C Lounge, which has an expansive bar with gleaming dark wood and big-screen TVs. Walto was no longer an active member of Lodge 5: He had been fired from the police force in 2010 for allegedly assaulting a woman while off duty, and was later sentenced to three to six months in prison.

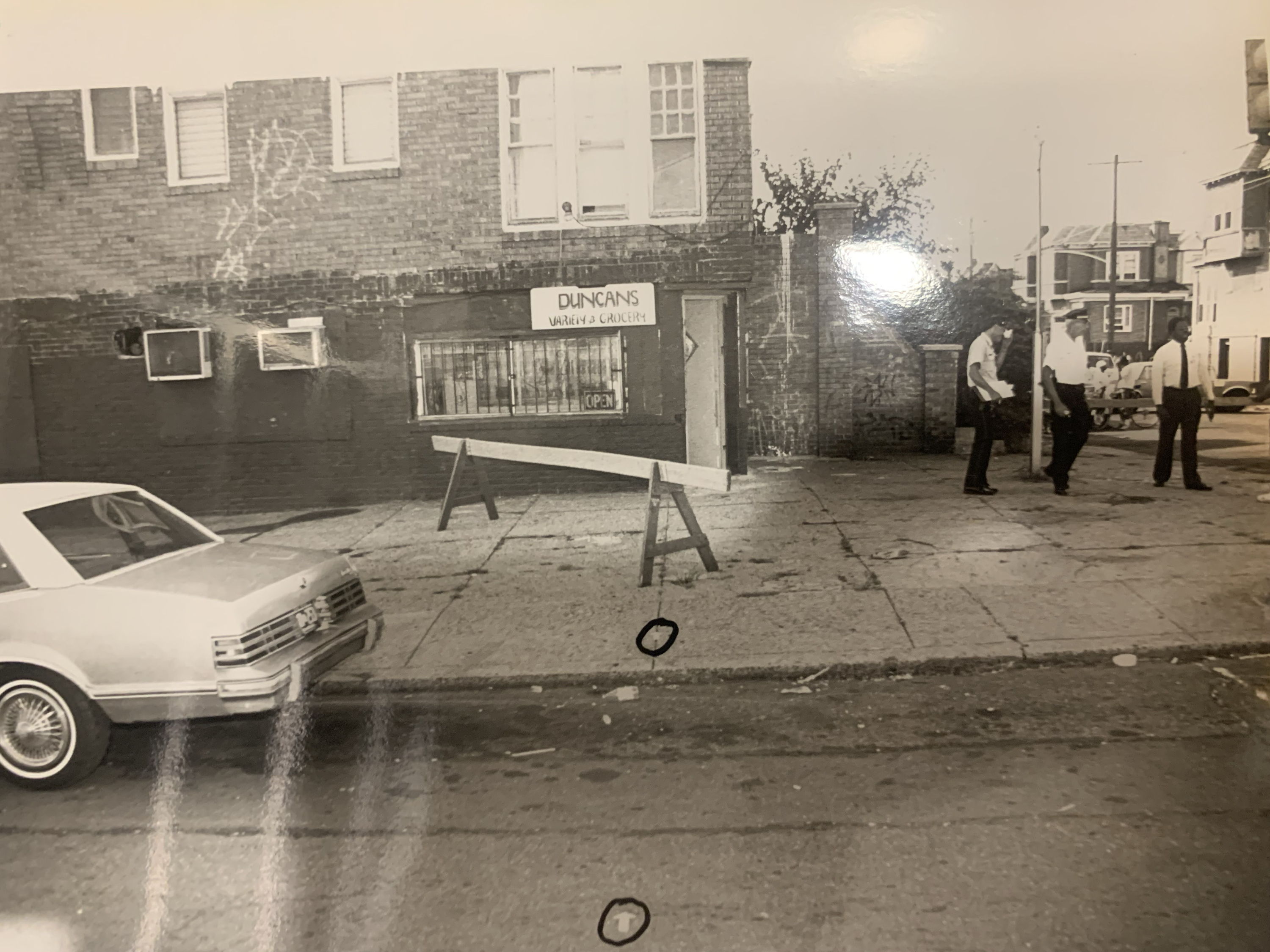

Walto left the bar just after 10 p.m. in his GMC Envoy. Rain was falling, the roads were slick, and Walto told a reporter that he lost control of his SUV when he tried to steer past a tractor-trailer on Caroline Road. He careered through the intersection at Comly Road and smashed into Anna Wakeman’s Chevrolet Equinox, which was sitting in her driveway.

The force of the impact crumpled the rear of the Equinox like an accordion and propelled it into Raymond Wakeman’s parked Chevrolet Silverado.

The Wakemans watched Walto stumble out of his Envoy, dazed and disoriented, then stagger along the sidewalk while clutching an Easter basket.

In a recent interview with The Inquirer, Walto said he does not remember if he drank any alcohol at the party, perhaps because he struck his head hard against the steering wheel.

“I was dizzy and messed up,” he said. “I didn’t know what was going on.”

Walto returned to his GMC and fumbled with a screwdriver in an attempt to remove an FOP-marked license plate from his SUV, the Wakemans said. He toppled over and the license plate remained in place, they said.

Walto said he was not trying to hide his link to the police union. “My tag fell off and I was trying to put it back on,” he said.

Police officers arrived at the scene and noted that Walto appeared to be under the influence of drugs or alcohol. They arrested him, and medics transported him to the hospital for chest pain, according to a police report. There is no mention in the report of Walto having suffered a head injury.

At the time of crash, Walto was also facing DUI charges in Montgomery County, court records show. In August 2019, he pleaded guilty there to driving under the influence and was sentenced to up to six months in prison; he spent 72 hours behind bars, he says.

His Philadelphia case was later dismissed.

The fact that the 7C Lounge has been connected to multiple drunken-driving incidents is troubling, experts say.

“The more accidents that result from serving alcohol at any bar, owned by the police union or anyone else, the more the public would be ordinarily concerned about the continuing operations of that establishment,” said Mark Carter, a longtime employer-side labor attorney and a member of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Labor Relations Committee.

“Here, you’ve articulated a pattern of behavior that would create a legitimate interest by the city or the prosecutor’s office about the continuing operations of that establishment.”

The state BLCE, which has the authority to issue sanctions, would not confirm or deny the existence of any investigation.

‘Watch our boy’

Hours before the Wakemans were nearly killed in their home in 2021, off-duty Philly cops had gathered for what was supposed to have been a somber affair: paying tribute to James O’Connor IV, a police corporal who had been shot and killed in the line of duty in March 2020.

The Crispin Tavern, a small bar on Holme Avenue in Northeast Philadelphia, staged a beef-and-beer fundraiser for O’Connor’s family that afternoon. Among the bar’s patrons was Campbell, who recalled drinking about six beers there before he climbed into his car and drove to the 7C Lounge, court records would later show.

He arrived at the FOP’s bar just after 5:20 p.m. His next three hours inside the establishment are detailed in a report written by Simonini, the liquor liability expert, who watched video footage from the bar’s security feed.

Campbell, who had been on the police force since March 2018, joined a table of five. Nearby, a man in a white shirt had trouble standing and nearly fell several times as he struggled to get his jacket on. He took a swing at another customer who tried to steady him.

Simonini noted that a server walked by the stumbling man four times but did not once ask if he was OK.

During a deposition, an attorney representing the Wakemans asked the 7C Lounge’s bar manager, Ernie Gallagher, about the stumbling man’s apparent intoxication.

Gallagher theorized that instead of being drunk, the man might have suffered from a neurological disorder.

“A lot of times we have a lot of people come in who don’t even drink, and, you know, they have [multiple sclerosis],” Gallagher said. “They fall and they go, ‘He wasn’t even drinking.’”

When reached for comment recently, Gallagher said: “I have no recollection. I have no comment. I have nothing.”

Simonini wrote that Campbell was drinking what appeared to be bottled beer, Twisted Tea, and mixed drinks out of plastic cups. In one 36-minute period, Campbell downed both his own drinks and others served to people at the table.

This consumption went unnoticed by 7C staff, Simonini wrote.

Gallagher said in his deposition that he considers “two drinks an hour” a safe amount to serve a patron.

“Clearly, Campbell and his party were served far more than ‘two drinks an hour,’” Simonini wrote.

At 7:40 p.m., Campbell returned to the bar, where it appeared Gallagher waved him off. Gallagher said in his deposition that he told Campbell, “Yo, you’ve had enough,” and he thought he told a bartender, “Watch our boy, Greg.” That bartender said in a deposition that he had no recollection of Gallagher’s comment.

Simonini wrote in his report that the 7C bartenders “served Campbell and his party 6-7 drinks at a time, and never watched where the drinks were going and to whom.”

Around 8:10 p.m., Campbell finished a bottle of beer and drank from a plastic cup at the bar. He headed to a bathroom but appeared unsteady, Simonini wrote.

Campbell then went outside. Surveillance video appears to show him losing his balance while walking around a snow bank toward his Dodge Dart.

Lawyers showed Campbell footage from the nearly three hours he spent at the 7C Lounge. Asked in his deposition whether he should have been refused alcohol, he answered, “Yes, based on my blood level of intoxication, yes.”

“Could you safely operate a motor vehicle when you left that bar?” the Wakemans’ lawyer asked.

“No,” he replied.

‘Gurgling on blood’

Campbell got behind the wheel at 8:17 p.m. He pulled onto Caroline Road and drove north toward Comly Road.

The posted speed limit in the area is 30 mph.

Campbell’s Dodge rocketed to 82 mph.

He zoomed past a stop sign, then crossed four lanes of traffic before striking a curb at 70 mph. The Dart thundered over the Wakemans’ snow-covered front yard.

As smoke and dust filled his home, Raymond Wakeman stood up, in shock at the devastation that surrounded him. Shards of crushed glass cut his bare feet.

“The car went right by my face and took my dog,” Raymond recalled. “It took Anna and Jax.”

Campbell climbed out of his car, but didn’t seem to “know where he was or what happened,” Raymond said.

Raymond couldn’t find his wife. But he heard faint sounds coming from the undercarriage of the car, which had come to rest in their son’s bedroom.

“She was gurgling, breathing, but gurgling on blood or something,” he said.

Raymond ripped vinyl siding off his house and used it to shovel rubble and debris from the front of Campbell’s car.

Finally, he saw her battered face.

“There was blood coming out of her ears, nose, and mouth,” he said. “Her leg was hanging off. She was barely breathing.”

Medics transported the Wakemans to Jefferson Torresdale Hospital. When the couple’s 17-year-old son, Patrick, arrived at the hospital, a doctor told him his mother was unlikely to survive the night.

“Honestly, I thought that was going to be the last time I’d ever see my mom,” he said.

Police arrested Campbell outside the splintered remains of the Wakemans’ house and transported him to Jefferson Torresdale, where he was handcuffed to a bed and treated for a cut to his forehead. He was dazed and there was a stench of alcohol on his breath, the police report said.

Then he received special visitors at his bedside, according to court records: unnamed FOP representatives.

Poplar, in his deposition for the Wakemans’ lawsuit against the FOP, was asked how the union is notified after an officer is arrested.

“So, this is just like an extra benefit that if you’re a cop that gets locked up, they call your union rep, 911 actually does?” the Wakemans’ lawyer asked.

“Yeah, that’s the only way we could get notified,” Poplar replied.

“I mean, look. There’s a lot of unions out there. Is there a 911 call going to the Teamsters if they get locked up to their union rep?” the lawyer asked.

“I don’t know,” Poplar replied. “I doubt it.”

Shortly after Campbell’s car bulldozed into the Wakemans’ home, a union representative called the 7C Lounge and told the staff to close for the night — even though closing time was not until 3 a.m. — because an officer had been involved in an accident after drinking there.

“I was following orders,” 7C Lounge bartender Andrew Reardon said in a deposition.

A.J. Thomson, the Wakemans’ attorney, alleged in court documents that the bar was closed to “prevent an investigation by Philadelphia Police and for any witnesses to be allowed to disperse prior to interviews. This was a possible homicide investigation that the FOP actively worked to torpedo.”

The FOP denied those allegations in a response to the Wakemans’ lawsuit, and its attorneys argued that bartenders did not serve Campbell while he was visibly intoxicated and did not cause the crash. The union vehemently denied allegations of negligence, recklessness, or carelessness.

At Jefferson Torresdale, Campbell conferred with Lodge 5 representatives and refused to take a blood-alcohol concentration (BAC) test.

Accident investigators obtained a warrant to draw Campbell’s blood, a process that took four hours. His blood was finally drawn and tested at 2:34 a.m., nearly six hours after his arrest.

Even with that delay, Campbell’s blood-alcohol level was almost three times the 0.08 legal threshold.

Those with a level between 0.25% and 0.40% are considered in a “stupor,” meaning they may be unable to stand or walk, and could be in an impaired state of consciousness and possibly die, according to Michael J. McCabe Jr., a toxicologist and expert on the effects of alcohol, who filed a report in the Wakeman lawsuit.

Herron, the liquor license lawyer, said in a case like this, he would expect the State Police Bureau of Liquor Control Enforcement to investigate and issue a citation. An administrative law judge would subsequently hear the case and decide what sanctions to impose.

The minimum fine for serving a visibly intoxicated person is $1,000.

“For more serious cases, if someone is injured, the administrative law judge has the discretion to impose larger fines or suspensions,” Herron said. “The problem with this case is that any investigation was sort of thwarted. It never really got to the point where there was an investigation.”

‘I should have died’

Anna Wakeman spent more than two months in a coma.

She had suffered a collapsed lung, a brain bleed, and a badly bruised heart muscle. Her spleen and her kidney were lacerated. Her sternum, thoracic vertebrae, collarbone, and 13 ribs were broken, along with her left leg.

She remained hospitalized for several weeks, then needed physical therapy.

“I should have died,” she said. “The only reason I’m here is God was breathing for me.”

The Wakemans’ insurance company paid off the mortgage on their severely damaged home. The couple couldn’t stomach the idea of ever setting foot again inside, so they sold the property to a developer and moved to West Virginia.

They each spoke at Campbell’s sentencing hearing in June 2022.

“I was normal before this,” Anna said through tears, telling the judge she still suffers from a traumatic brain injury and lives in constant pain.

Campbell spent about a year in prison, and then was placed on house arrest.

“The man who did this to me walks free,” Anna Wakeman said in a recent interview “But I don’t have peace. We lost everything. I’m in pain all the time every single day. I’m in prison in my own body.”

The Wakemans sued the FOP under Pennsylvania’s Dram Shop Law, which holds bars liable if they serve alcohol to a drunk patron and that decision leads to injuries or damages.

In 2024, the case was settled for an undisclosed amount.

Records the Home Association filed as a 501(c) nonprofit do not require the kind of specificity that would show how the organization paid the Campbell settlement, or whether any payments were made related to the 2019 Walto crash or the unreported 2021 parking lot incident. An August investigation by The Inquirer found that while the union controls an array of nonprofits — including the Survivors’ Fund, Lodge 5, and the Home Association — its finances are opaque and difficult to track, in part because large amounts of cash move through the organizations.

Nearly five years after the accident that upended her life, Anna Wakeman still questions why 7C Lounge bartenders didn’t stop serving Campbell, or at least call him a cab, that evening.

“They let him leave knowing he was going to get behind the wheel,” she said. “These are officers of the law. They should hold the law sacred. There shouldn’t be different rules for them.”