To hear the Parker administration officials tell it, moving the Rocky statue from the bottom of the Philadelphia Art Museum steps to the top is a victory for the underdog.

The new location, which received a green light from the Art Commission on Jan. 14, will certainly create a dramatic, Instagrammable moment for tourists, and further elevate the Rocky brand (and value).

But it’s no victory for Philadelphia residents, who remain the true underdog in this saga. Allowing the old movie prop to dominate the Parkway’s iconic vista is simply the latest in a series of decisions that have privatized the Art Museum’s gorgeous, landscaped grounds.

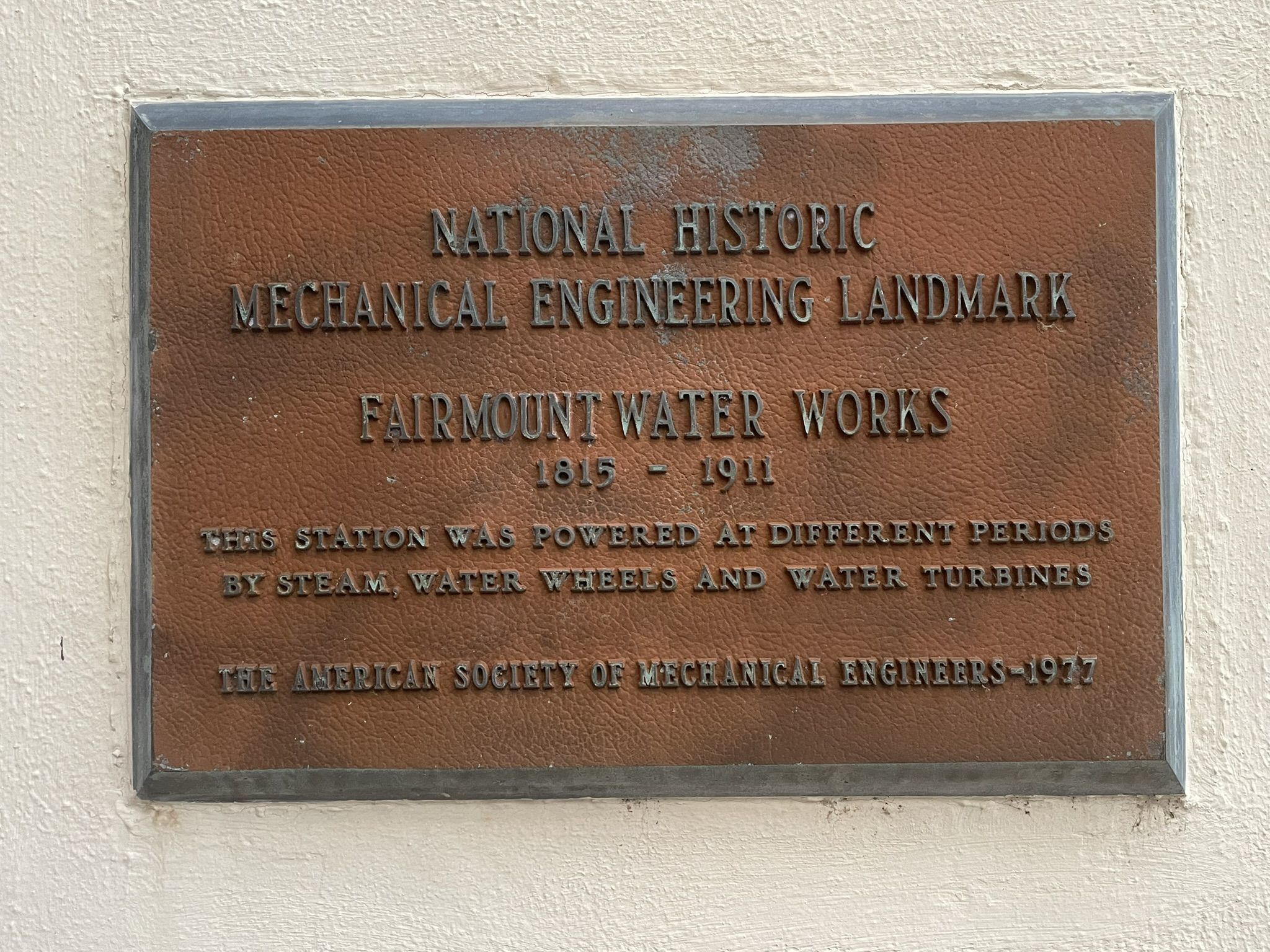

If you walk to the back of the museum, you’ll find the most egregious example of Philadelphia’s zeal for monetizing public space: the sprawling Cescaphe banquet operation at the Fairmount Water Works.

While the main Engine House had been used as a restaurant in the past, the city allowed Cescaphe to take over the entire complex in 2021. Today, the Water Works is surrounded with a cordon of server stations, portable restrooms, and covered walkways.

Cescaphe’s presence has drastically limited the public’s access to this historic landmark, a scenic spot where generations have come to stroll and take in views of the Schuylkill. Although visitors are permitted to wander though the Water Works’ classically inspired temples and colonnades when no events are going on, who would know that, given the messaging conveyed by Cescaphe’s formidable barricades?

Preparations for evening events often start in the afternoon, further limiting access. Every spring, Cescaphe installs an enormous glass party room on the pier known as the Mill House Deck. It remains in place until late fall, which means the public gets to use the overlook only during the coldest months of the year.

Rocky already has a good spot

Moving the Rocky statue to the top of the steps might seem like a modest imposition by comparison, but the new location will interfere considerably with the public’s enjoyment of the space.

Since people with mobility limitations will have trouble climbing the 72 steps to the top of the museum’s grand staircase, they’ll need transportation. The Philadelphia Visitor Center — the initial advocate for the new location — has offered to run a shuttle bus around the museum apron every 15 minutes. Better watch out when you’re taking that selfie!

During the recent Art Commission hearings, the city’s two top cultural officials, Valerie V. Gay and Marguerite Anglin, argued that the Rocky statue deserves a higher profile perch because it’s a unique tourist attraction. They noted that the statue has been the subject of books and podcasts and will soon be the focus of a major Art Museum exhibition, “Rising Up: Rocky and the Making of Monuments,” curated by Monument Lab’s Paul Farber.

Yet, given the added complications, it’s hard to understand what the city gains by changing the statue’s location.

Rocky’s current home — a shady grove at the bottom of the steps — has been a huge success. The statue was installed there in 2006, after years of shuttling around Philadelphia, from the museum to the sports complex and back. In a typical year, 4 million people make the pilgrimage to see Rocky, the same number who visit the Statue of Liberty annually.

Because the grove is so close to the street, there are no accessibility issues. Tour buses and cars can pull up to the curb, allowing people to jump out for a quick selfie. Sometimes there’s a line for photos, but the mood is always festive, with visitors and locals mingling along the sidewalk. Anyone who wants to reenact the fictional boxer’s run up the museum stairs can do that, too.

Yes, this site occupies a piece of the museum’s grounds. But the intrusion is relatively discreet. Considering how well this location works, why change it? It’s not like there was a huge public clamor to give Rocky more prominence. When Inquirer columnist Stephanie Farr polled readers in September, most respondents said they were happy to keep the statue in its current location — or get rid of it entirely.

Only a single person testified at the Art Commission’s Jan. 14 hearing — and he argued against the move. Several civic organizations, including the Design Advocacy Group (DAG), sent written statements urging the city to reject the proposal.

“All we’re doing is glorifying Sylvester Stallone, who sells merchandise at bottom of the steps,” complained David Brownlee, a member of the DAG board and a renowned University of Pennsylvania art historian who has written a history of the Art Museum.

Those Stallone-licensed souvenirs are sold in the “Rocky Shop,” a metal shipping container that was allowed to encroach on the plaza at the base of the museum steps in 2023. Although the metal structure doesn’t take up as much public land as Cescaphe’s banquet operation, it clunks up the approach to the museum’s elegant stone staircase.

Initial reports said the Visitor Center, which pushed for the shop, would get a cut of the sales. Yet when I asked how much money that partnership had yielded, a spokesperson for the independent tourism agency declined to answer. The Visitor Center is now run by Kathryn Ott Lovell, who was parks commissioner when the department signed off on Cescaphe’s 2021 expansion at the Water Works.

The exorbitant cost of moving

What jumped out at me during the Art Commission hearing was the cost of moving the bronze sculpture and setting it up on a new base.

Creative Philadelphia, the city department overseeing the move, originally estimated the job would run about $150,000. Now it says the price could rise to $250,000. Those figures don’t include the cost of operating the shuttle, which will be borne by the Visitor Center.

To put those numbers in context, consider the base payment the city receives from Cescaphe annually for operating a banquet hall at the Water Works: $290,000.

When Cescaphe was given permission to occupy the Water Works complex in 2021, the city said the arrangement was necessary because the parks department could no longer afford to adequately maintain the property. In addition to rent, the agreement generated about $187,000 annually in concession fees between 2015 and 2022 for the city.

That income isn’t peanuts, but is it really worth severely limiting public access to such an iconic Philadelphia landmark? What’s the point of monetizing our parks if the businesses prevent us from enjoying them?

The privatization of such beloved sites is the direct result of city government’s unwillingness to properly fund its parks. For years, Philadelphia has spent far less than peer cities on green space. Maintenance declined to the point where some parks became unusable.

Rather than devote more money to this basic public amenity, the city has increasingly outsourced its parks to private managers. Enormously popular destinations, such as Dilworth Park and Franklin Square, are run by independent groups.

But there’s a crucial difference between those private managers and the likes of Cescaphe. First, they’re nonprofits, not businesses. They exist to serve the public. While it’s frustrating when they close their parks for private fundraising events, all the money they raise goes back into improving the parks for the public’s use.

With the Cescaphe deal, the city has crossed a line. Cescaphe is a money-making business that runs the Water Works for its own benefit. In theory, the rent and concession fees are supposed to be invested in the maintenance of the complex, which was considered one of the wonders of the world when it opened in 1815. But it’s Cescaphe, not the public, that benefits from the improvements.

It’s not even clear that Cescaphe is doing the promised maintenance. The Engine House suffered a serious fire in November, and the company still has several outstanding building code violations.

When asked about the citations, a spokesperson for Parks & Recreation described the infractions as minor. “Cescaphe has been a great partner,” Commissioner Sue Slawson said in a statement.

To be clear, there is a big difference between leasing a public building to a restaurant concession and privatizing public space for the sole use of a single business. Restaurants are open to everyone. They also provide services, such as restrooms, that the public can use. It’s a win-win: The city makes a little money on the deal, and the public gets a nice amenity.

The city had the right idea when it leased the Water Works’ Engine House to a restaurateur in the early 2000s. But instead of finding a replacement when that restaurant shut down in 2015, the city turned the complex over to Cescaphe. This April the banquet company’s lease will come up for renewal. It’s time to go back to the original model.

Wouldn’t it be great to grab a sandwich at a Water Works cafe after a long walk or bike ride along the Schuylkill River Trail? The trail, which just completed a spectacular extension, does not have a single cafe between its new Grays Ferry terminus and the museum, apart from a small snack bar at Lloyd Hall. Philadelphia has plenty of great restaurateurs who would jump at the chance to operate in a prime spot like the Water Works.

People have framed the Rocky discussion as a clash between elites, who object to the glorification of a movie prop as art, and the mass of fans who believe the statue embodies their aspirations.

The reality is, there’s nothing less democratic than turning over the public’s land to private companies driven by their own gain.

An earlier version of this column listed FDR Park as one of several city parks that are run by private managers. The Philadelphia Department of Parks & Recreation operates the park and provides workers to staff it.

This story has been updated to remove the Schuylkill River Trail from a list of private managers because the Schuylkill River Development Corp. has a different type of contractual agreement with Philadelphia’s Department of Parks & Recreation and does not lease the land it oversees.