Heather Huot, the top executive at Catholic Charities, named her only daughter after Lidia, a homeless, mentally ill, and often cranky elderly woman she met as a young social worker at Women of Hope Vine, a transitional housing facility run by the organization Huot now leads.

As “mean spirited” as Lidia was, Huot said, Lidia still celebrated forsythia.

When their bright yellow blossoms heralded winter’s end, Lidia would drag Huot outside to marvel. “Despite all the hardships,” Huot said, “there are things to be celebrated.”

Which brings us to the Christmas holiday season.

Even if it were possible, which it’s not, to overlook all the troubles in our world, with wars and starvation, or even to overlook all the troubles in our nation, there would still be the troubles of the season — too much work, too much loneliness, too many struggles.

Where’s the forsythia?

Two weeks ago, it was outside the Archdiocesan Pastoral Center in the form of a living Nativity scene, complete with a wee baby goat named Lady, an artificial-snow machine, an actual camel, and an elementary school choir in their Catholic school uniforms singing “Joy To the World.”

Yes, “Joy To The World,” because 500 children, some of whom live in tough circumstances, got a chance to celebrate Christmas and with it, maybe, the hope that the holiday brings. It was the 70th annual Archbishop’s Benefit for Children, a Catholic Charities of Philadelphia event funded by a grant from the Riley Family Foundation. No expense was spared.

More than 60 volunteers from area high schools lunched on pizza and cookies before heading across the street to a lavishly decorated ballroom in the Sheraton Philadelphia Downtown. Balloons, banners, party favors, huge plates of cookies, a container of ice cream cups, and a bucket of all different flavors of milk awaited at each table. Kids and chaperones crowded the dance floor, only to make way for an appearance by Santa, who high-fived his way around the ballroom. At the party’s end, the volunteers sprang into action distributing bags of toys — all beautifully wrapped.

In a way, the party is a metaphor for Catholic Charities as a whole. Both the party and the organization are big and multifaceted with lots of moving parts, involving all types of people, not only Catholics.

Each year, Catholic Charities spends about $158 million to run about 40 different programs in four main categories — care for seniors; support for at-risk children, youth, and families; food and shelter; and its biggest category, many-pronged assistance for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities and their families.

As an overview, there’s housing for at-risk youth in Bensalem. In Philadelphia, people may be familiar with St. John’s Hospice on Race Street, which provides food, showers, shelter, and case management to men. There are several smaller transitional housing shelters for women in the city.

Social workers funded by Catholic Charities assist students at six Catholic high schools across the region. Other social workers handle case management under contract with the City of Philadelphia. A program teaches teenagers involved in the juvenile justice system about conflict resolution. Family navigators step in to assist families with issues ranging from employment to parenting support. There are adoption and foster-care services.

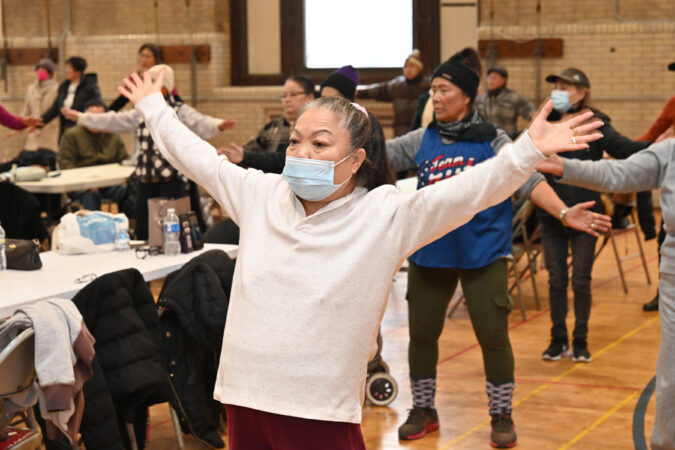

For the elderly, Catholic Charities supports senior centers and works to help seniors stay independent through case management.

Just over half of Catholic Charities’ annual budget is allocated to supporting people with intellectual or developmental disabilities. A major focus is housing for adults. For example, at the Divine Providence Village in Springfield, Delaware County, 72 women live in six cottages on a 22-acre campus with a pool, greenhouse, and picnic pavilion.

In addition, there is employment support, a day program, field trips, a family-living program, and respite care to help families overwhelmed by caregiving responsibilities.

Nearly 80% of Catholic Charities’ funding comes from government sources, which, these days, requires Huot to focus her prayers. “I ask God to help me get through this and to give me the strength and the people around me to get through this,” she said. “At the same time, we have to recognize that God provides in ways you don’t expect.

“We’ve been blessed with generous benefactors who have stepped in,” she said. “The Philadelphia community is incredibly generous. We get a bad rap as the people who throw snowballs at Santa Claus, but Philadelphians will give you the shirt off their backs. They are passionate about caring for one another.”

The generosity moved Lakisha Brown to tears as she shepherded her two children and a third to the party earlier this month. Brown, 44, lives in a three-bedroom subsidized housing apartment at Catholic Charities’ Visitation Homes in Kensington.

“This is the best I ever lived,” she said. But, she said, just outside her door “is a constant reminder of where I came from and where I never want to go.”

Brown’s father died when she was in elementary school and her mother struggled with alcohol addiction. Brown left home when she was 16 under the protection of a man who started their relationship with gifts and ended it with beatings.

“He left me in a coma,” she said.

Brown had her own struggles with addiction. She spent many nights without a roof over her head. If lucky, she could sleep in safety in an abandoned car on a quiet block. One night, she went to a party in a hotel. When she woke up, her clothes were off. Whatever happened wasn’t consensual.

Soon after, she learned she was pregnant and, knowing that, she vowed to give her baby a clean birth. She found a drug program and a place to live. Slowly, through housing and support from Catholic Charities, she rebuilt her life.

“They help us with budgeting, with money management,” said Brown, who relies on disability, welfare, and food benefits while trying to cope with her own mental health issues. “When we get some money, we want to spend it on the children. We were parenting out of guilt and shame.”

Those are the big things, but what Brown wants people to understand is that the level of care is deep, personal, and specific. It’s being able to ask a staff person for a roll of toilet paper and trash bags — basics that are sometimes unaffordable when money must be allocated to food and shelter.

“A mom’s job is never done,” she said, explaining why people should donate to Catholic Charities. “It is needed for mothers who come from nothing. It is needed.”

About Catholic Charities of Philadelphia

People served: 294,000 annually (in the 2023-24 fiscal year)

Annual spending: $158.6 million across four pillars of mercy and charity

Point of pride: Catholic Charities of Philadelphia is the heart of the church’s mission in action, serving all people regardless of background. With decades of experience, nearly 40 comprehensive programs, and deep community partnerships, Catholic Charities turns compassion into action, and action into lasting and impactful change.

You can help: By serving meals, volunteering at a food pantry or shelter, hosting a food or clothing drive, and sharing your gifts and passions with seniors.

Support: phillygives.org

What your Catholic Charities donation can do

- $25 provides five nutritious lunches for children through the School Lunch Program.

- $50 provides three hot lunches at St. John’s Hospice for individuals experiencing food insecurity.

- $100 provides an instructor and supplies for an art or recreation class for 50 to 100 seniors at a senior community center.

- $275 provides one week of groceries for a family of four.

- $325 provides a mother with formula, diapers, and wipes for a month.

- $550 provides emergency shelter and meals for a week for someone experiencing homelessness.