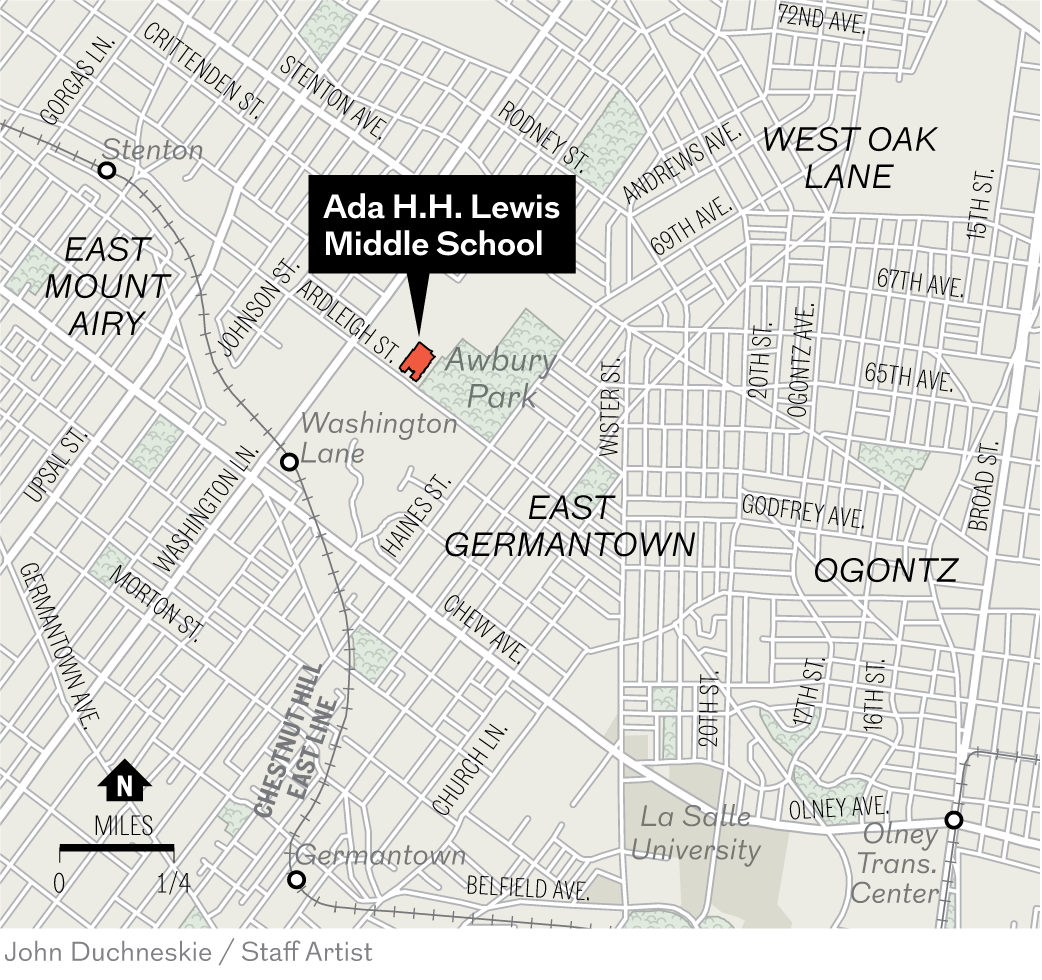

For years, Northwood Academy Charter School was a stable Philadelphia charter — the kind of place where teachers and administrators stayed for decades, and children thrived.

But in the last few years, the school, on Castor Avenue in Frankford, has cycled through dozens of administrators and teachers and test scores have dropped. Academics have suffered, according to interviews with a number of parents and staff, who say the school feels less safe, and staff morale is low.

The school’s five-year charter expires this year, but Northwood’s renewal is on hold, The Inquirer has confirmed, because the district’s Inspector General’s Office is reviewing information about Northwood. The exact nature of the investigation is unclear.

The Inquirer spoke to and reviewed testimony from more than a dozen parents and current and former Northwood staff. Nearly everyone interviewed requested anonymity for fear of reprisal; some who spoke out at meetings have received cease and desist letters threatening litigation from a consultant who provides human resources services to Northwood.

“When we first got there, there was stability at the school — everyone was there since almost the beginning,” one parent said. “Now, in the last five years, we have had 20 administrators change over. The kids can’t get comfortable with the teachers, because they don’t know if they’re going to be there a long time.”

Northwood, which opened in 2005, educates 800 students in grades K through 8. As a charter, it’s independently run but publicly funded; the Philadelphia school board authorizes its funding but does not manage its operation.

School officials say the Northwood turnover is not excessive, but rather a function of its board of trustees’ move to steer the school to better outcomes.

“Our goal here is to just move forward and help our students achieve,” said Kristine Spraga, a longtime board of trustees member who now serves as the board’s treasurer.

The board’s challenge, human resources consultant Tracee Hunt said, “is getting the person who has that strategic focus, who doesn’t necessarily operate more like a principal than a CEO. What happens is we’ve hired what we thought were great hires, and then if they decide, ‘This is a little bit too much for me, the board doesn’t have any control over that.’”

The board this month hired former Central Bucks School District Superintendent Steven Yanni to lead the school.

A pivot point

Northwood handled human resources in-house in its early days. When a principal left in 2018, there was some unrest among faculty after a number of teachers were shifted around.

Shortly thereafter, one board member suggested bringing in Total HR Solutions, a New Jersey-based provider that had worked with some other Philadelphia charters, to manage those services.

That was a pivot point for the school.

Hunt was charged with examining the school’s practices. She found “a lack of fair and equitable hiring practices,” she said in an interview last week, “a massive amount of nepotism,” and inadequate staff diversity — the school educates mostly Black and Latino students but its staff was mostly white.

“Through natural attrition, we have the opportunity to have fair and equitable hiring practices so that then you improve in your areas of diversity in just a natural way, versus feeling like you have to displace people,” said Hunt.

Some current and former staff see things differently. The earlier version of Northwood wasn’t perfect, they said, but it was cohesive, and under Total HR, that changed.

Adam Whitlach, a longtime Northwood school counselor, said Total HR “came in with the idea of ‘demolish, and re-create something from nothing.’ They were mixing it up for the sake of mixing it up. They treated it like it was a turnaround school, but it wasn’t, there was an existing community. They attempted to sell them a story that our school was failing and racist, but people didn’t believe that.”

In 2021, the school’s longtime CEO, Amy Hollister, abruptly left Northwood with no notice to the staff and families with whom she had built a strong rapport.

“It was out of the blue, and then everybody else started leaving,” another Northwood parent said. As with others, the parent asked not to be identified for fear of blowback. Parents began attending board meetings — at one, Hunt stood up, the parent said, “and began to tell us how the teachers want a more diverse school, and that’s the reason why all this upheaval was happening.”

The parent, who is a person of color, said they were not bothered by the staff’s demographic balance. “Those teachers loved our children. Everybody knew you, you didn’t have to go past security, and they welcomed every parent, every child. There weren’t a lot of discipline issues, because they had relationships with our kids,” the parent said.

More departures

Changes accelerated after Hollister left.

“Parents were grabbing me by the arm and saying, ‘Whitlach, tell me what’s going on here,’” the former counselor said. “The bullhorns came out, the security guards dressed all in black came out.”

(Whitlach was ultimately fired after 15 years at the school after, he said, he complained publicly about the school pushing staff out. Students walked out in protest of his departure.)

The departures affected academics too. A third parent said she was frustrated by “no curriculum, no books.”

Administrations came and went. Audrey Powell came to Northwood as an assistant principal in 2023, following then-CEO Eric Langston, who has since left; Langston left this summer, and Powell resigned soon after.

The reason for her departure?

“I just didn’t agree with the direction or the choices of the board,” Powell said. She repeatedly brought concerns to the board that were ignored, she said. In particular, she was alarmed by the board’s relationship with Total HR and Hunt’s “overreach” at Northwood, Powell said.

“I don’t think there were enough checks and balances,” Powell said. “I feel like [Total HR’s] contract incentivizes there to be turnover — she directly financially benefits from there being turnover.”

Northwood paid Total HR $1.4 million between 2020 and 2023, according to public records. That included base fees for Total HR’s services, including an HR generalist who works at Northwood but is paid by Total HR, and also per-position search fees for administrative positions and board seats.

“The constant turnover is a misuse of taxpayer dollars, and it’s a disservice to kids, to the teachers,” said Powell. “There can’t be progress when there is that much turnover. It’s two steps forward and four steps back.”

Hunt dismissed the notion that she was simply out to make money.

“We have these contracts that are negotiated,” said Hunt, whose firm works across industries. “Everything that I bring to Northwood, I bring below market rate.”

The school district’s charter chief, Peng Chao, said Northwood’s spending on human resources appears to be more than is typical.

“This level of spending is not what we usually see for this type of scope of work,” Chao said. “While we recognize the staffing challenges that schools are navigating, it is important for schools to remain mindful of fiscal constraints as we all work through an uncertain budget environment.”

Yanni, who began as Northwood’s CEO Oct. 6, said while Total HR provides services, ultimately, hiring and firing decisions rest with the CEO.

“HR is an adviser to us, so HR doesn’t make the hiring and firing decisions, they provide the guidance from the place of compliance and the law,” said Yanni.

‘Beyond frustrated’

Staff and parent concerns about Northwood are not new. At board of trustees meetings, speakers often give impassioned testimony on the subject.

At last week’s trustees’ meeting, kindergarten teacher Emily Parico told the board that “something nefarious is going on at Northwood, and you sit by, silent and complicit. Northwood used to be a learning sanctuary. It wasn’t perfect, but it was a place where students, staff, and families felt safe and loved.”

Parico is the Northwood teachers union’s vice president. Most city charter teachers are not unionized; Northwood’s voted to form a union in 2023 amid turmoil at the school.

Kim Coughlin, a fourth-grade teacher and the union president, said the school continues to be roiled.

“Every day, teachers and staff are thinking of walking away, and two just did yesterday,” said Coughlin. “And our families are beginning to look elsewhere, because they feel the shift. The school that we once knew and loved has become unrecognizable.”

Questions and threats of legal action

When Langston, the CEO prior to Yanni, left suddenly in August, dozens of families and staff asked the board for answers, but none were forthcoming, said Kevin Donley, the school’s psychologist.

“I’m beyond frustrated,” said Donley, who’s secretary of the union. “And deeply disappointed by the manner in which the board of trustees has governed our school in recent months and years.”

At least 50 people sent letters to the board of trustees expressing concern about further turmoil after Langston’s departure, Donley said. As far as he knows, not one person heard back, either in a letter or any kind of message.

Both Hunt and the board have sent letters threatening some who speak out with legal action; Hunt said she won a legal challenge against one parent who falsely said she had been fired by a previous client. (The client, Hunt said, moved HR services in-house and did not fire her.)

“It’s not uncommon to have a few naysayers, but eventually when you start seeing the fruit of all this board’s labor, the reason I stick in here is because I watch them stay so focused on the kids,” Hunt said.

School officials told The Inquirer that the staff and parents who have spoken out represent “a very small number of people who are quite passionate,” but not representative of all staff and parents.

“I don’t see that the vast majority feel the same,” said Spraga, the board treasurer. “Otherwise, we would have those indicators in things like the engagement surveys, right?”

Spraga, Hunt, and board president Warren Young said staff and community engagement surveys do not match the sentiments expressed at board meetings.

New leadership under Yanni

The Northwood CEO job is Yanni’s first foray into the charter sector; he was previously superintendent in the Lower Merion, Upper Dublin, and New Hope-Solebury school systems. Yanni was terminated as the Central Bucks superintendent last week over allegations that he mishandled child abuse allegations in a special education classroom — a contention he denies.

Yanni said he’s thrilled to be at Northwood, where class sizes are small — 23, typically — and there’s a feeling of welcome.

“There’s passion here,” Yanni said. “And it’s not just the staff, it’s the kids too — this is their school. Kids really feel like Northwood is their home, and we have engaged families.”

Northwood is completely full, with a waitlist of 200 students per grade level, Yanni said, and applications are already coming in for the 2026-27 school year.

In the 2018-19 school year, 64% of Northwood students met state standards in reading, and 30% in math; in the 2024-25 school year, the last year for which scores are publicly available, 31% of Northwood students hit the mark in reading and 11% in math. In 2018-19, Northwood beat Philadelphia School District scores (35% proficiency in reading, 20% in math) and in 2024-25, the district did better (34% proficiency in reading, 22% in math).

Yanni said Northwood is a school on the rise and is beginning to implement positive behavioral supports to improve school climate. It’s also in the early days of an academic intervention process to identify and target individual students’ skill gaps.

“I think we’re going to see dramatic gains this year,” said Yanni.

Northwood “is a school that people stick with,” he said. And though the city has plenty of choices for families, “we’re going to start a strategic planning process, and really kind of blow the doors off. You hear about KIPP, and you hear about these large charter networks and then there’s little tiny Northwood. How do we make it the beacon, the flagship?”