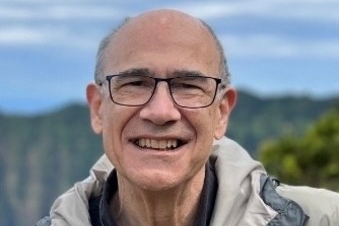

Robert E. Booth Jr., 80, of Gladwyne, renowned pioneering knee surgeon, former head of the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at Pennsylvania Hospital, celebrated antiquarian, professor, researcher, writer, lecturer, athlete, mentor, and volunteer, died Thursday, Jan. 15, of complications from cancer at his home.

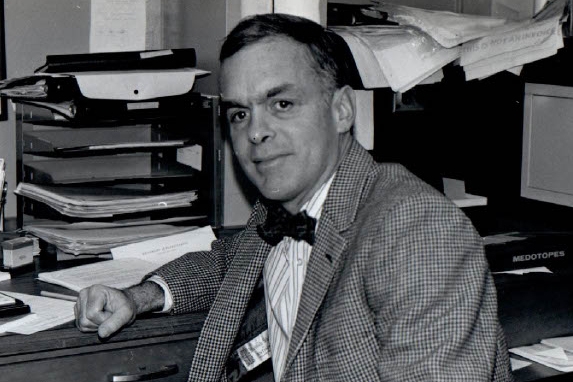

Born in Philadelphia and reared in Haddonfield, Dr. Booth was a top honors student at Haddonfield Memorial High School, Princeton University, and what is now the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He was good at seeing things differently and went on to design new artificial knee joint implants and improved surgical instruments, serve as chief of orthopedics at Pennsylvania Hospital, and mentor celebrated surgical staffs at Jefferson Health, Aria Health, and Penn Medicine.

He joined with two other prominent doctors to cofound the 3B orthopedic private practice in the late 1990s and, over 50 years until recently, performed more than 50,000 knee replacements, more than anyone, according to several sources. Last March 26, he did five knee replacements on his 80th birthday.

In a tribute, fellow physician Alex Vaccaro, president of Rothman Orthopaedic Institute, said: “He restored mobility to thousands, pairing unmatched technical mastery with a compassion that patients never forgot.”

In a 1989 story about his career, Dr. Booth told The Inquirer: “It’s so much fun and so gratifying and so rewarding to see what it means to these people. You don’t see that in the operating room. You see that in the follow-ups. That’s the fun of being a surgeon.”

Friends called him “a legend in his profession” and “a friend to everyone” in online tributes. He was known to check in with patients the night before every surgery, and a colleague said online: “Patients were all shocked by his compassion.”

Dr. Booth was also praised for his organization and collaboration in the operating room. “His OR was a clinic in team work and efficiency,” a former colleague said on LinkedIn.

He told Medical Economics magazine in 2015: “I love fixing things. I like the mechanics and the positivity of something assembled and fixed.”

His procedural innovations reduced infection rates and increased success rates. They were scrutinized in case studies by Harvard University and others, and replicated by colleagues around the world. Some of the instruments he redesigned, such as the Booth retractor, bear his name.

He was president of the Illinois-based Knee Society in the early 2000s and earned its 2026 lifetime achievement award. In an Instagram post, colleagues there called him “one of the most influential leaders in the history of knee arthroplasty.”

He was a professor of orthopedics at Penn’s school of medicine, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, and the old Allegheny University of Health Sciences. He loved language and studied poetry on a scholarship in England after Princeton and before medical school at Penn. He told his family that his greatest professional satisfaction was using both his “manual and linguistic skills.”

He was onetime president of the International Spine Study Group and volunteered with the nonprofit Operation Walk Denver to provide free surgical care for severe arthritis patients in Panama, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and elsewhere. Colleagues at Operation Walk Denver noted his “remarkable spirit, profound expertise, and unwavering commitment” in a Facebook tribute.

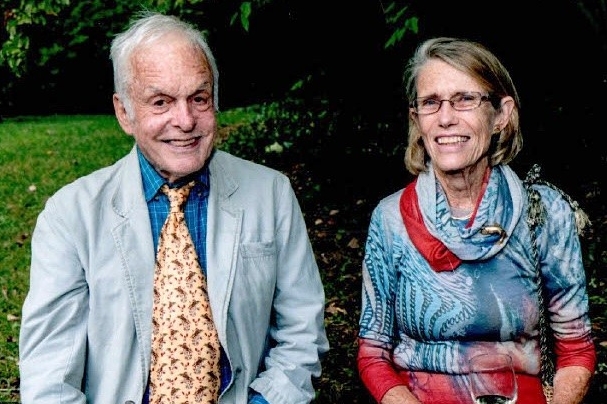

At home, Dr. Booth and his wife, Kathy, amassed an extensive collection of Shaker and Pennsylvania German folk art. They curated five notable exhibitions at the Philadelphia Antiques Show and were recognized as exceptional collectors in 2011 by the Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks.

He lectured widely about art and antiques, and wrote articles for Magazine Antiques and other publications. He was president of the American Folk Art Society and active at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Canterbury Shaker Village in New Hampshire.

“He was larger than life for sure,” said his daughter, Courtney.

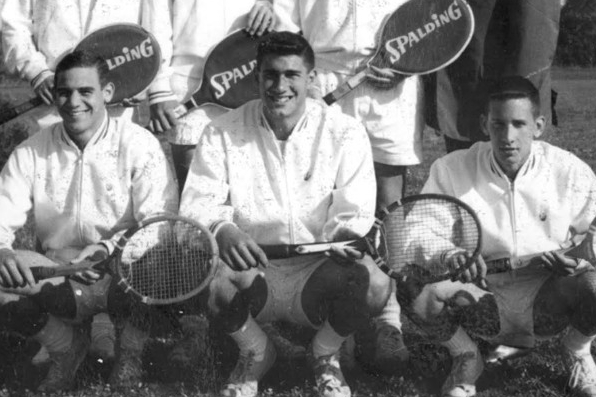

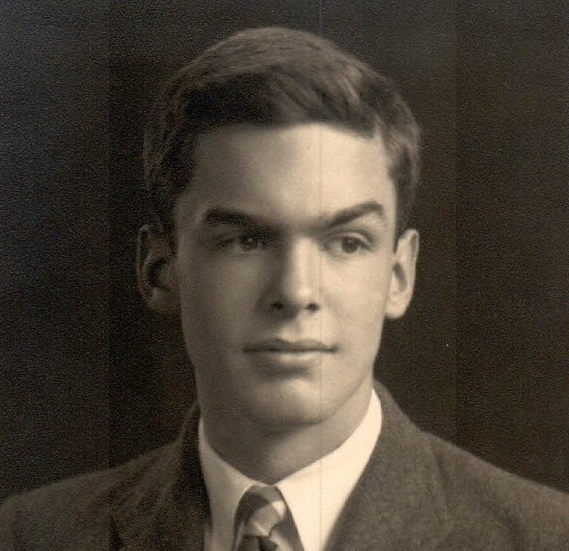

Robert Emrey Booth Jr. was born March 26, 1945, in Philadelphia. He was the salutatorian of his senior class and ran track and field at Haddonfield High School.

He earned a bachelor’s degree in English at Princeton in 1967, won a letter on the swimming and diving team, and played on the school’s Ivy League championship lacrosse team as a senior. He wrote his senior thesis about poet William Butler Yeats and returned to Philadelphia from England at the suggestion of his father, a prominent radiologist, to become a doctor. He graduated from Penn’s medical school in 1972.

“I always liked the intellectual side of medicine,” he told Medical Economics. “And once I got to see the clinical side, I was pretty well hooked.”

He met Kathy Plummer at a wedding, and they married in 1972 and had a daughter, Courtney, and sons Robert and Thomas. They lived in Society Hill, Haddonfield, and Gladwyne.

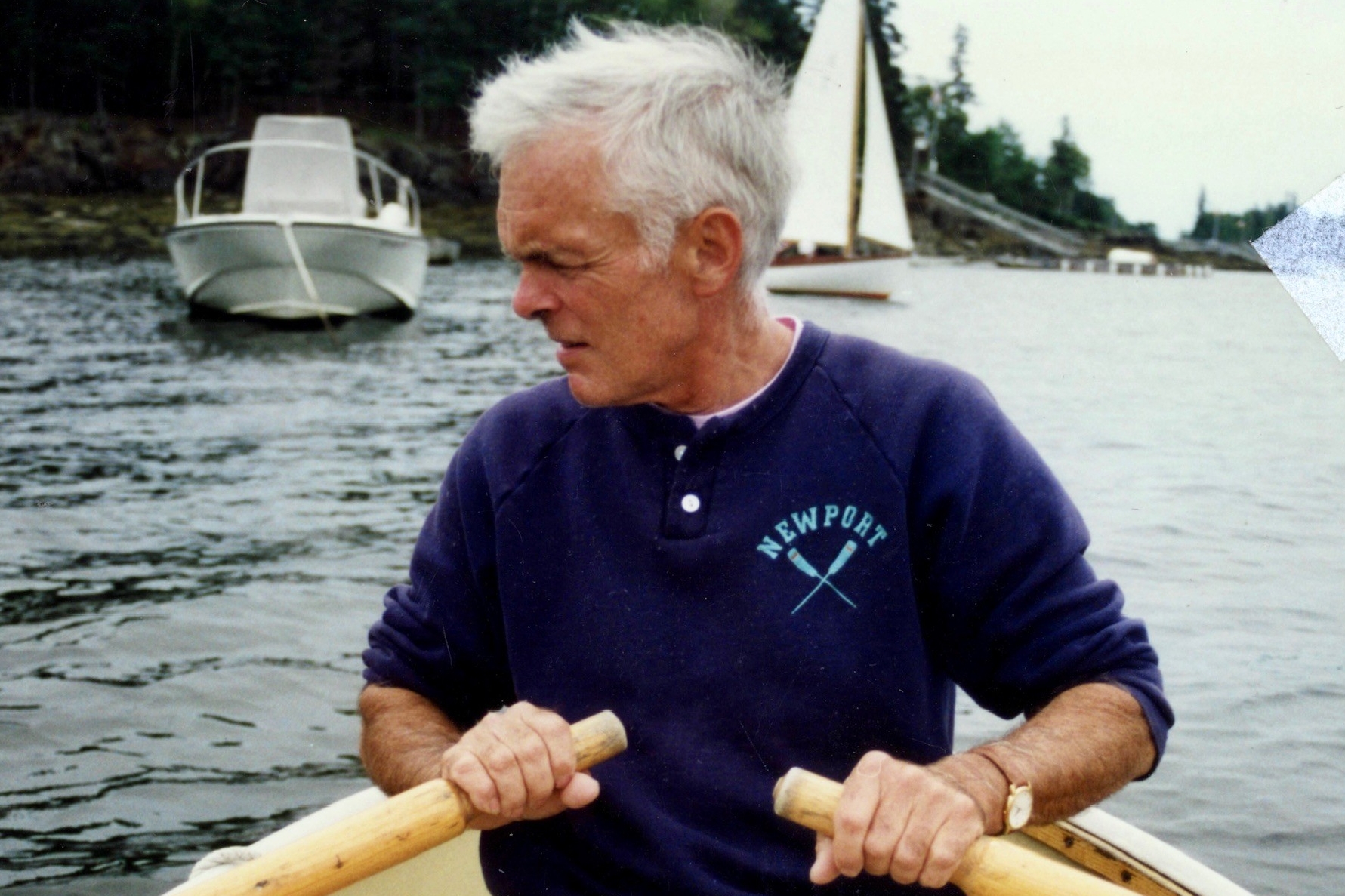

Dr. Booth liked to ski and play golf. He was an avid reader and enjoyed time with his family on Lake Kezar in Lovell, Maine.

“He was quite the person, quite the partner, and quite the husband,” his wife said, “and I’m so proud of what we built together.”

In addition to his wife and children, Dr. Booth is survived by six grandchildren and other relatives.

A private celebration of his life is to be held later.

Donations in his name may be made to Operation Walk Denver, 950 E. Harvard Ave., Suite 230, Denver, Colo. 80210.