Naval Square, as it is now known, has been many things before becoming a gated community of expensive condos on the banks of the Schuylkill in a neighborhood with many names.

The Inquirer calls the area Schuylkill, but others might use Devil’s Pocket, Southwest Center City, or Graduate Hospital, the newest name on the block.

But whatever you call it, the 24-acre plot of land on Grays Ferry Avenue has been associated with the Navy since 1827 and has the unusual distinction of being the final resting place of Dexter, the Navy’s last working horse.

A reader interested in learning more about the horse — the questioner thought it was a mule — asked about it through Curious Philly, the Inquirer and Daily News question-and-answer forum through which readers submit questions about their communities and reporters seek to answer them.

First, a little history about the site.

The Philadelphia Naval Asylum, a hospital, opened there in 1827.

From 1838 until 1845, the site also served as the precursor to the U.S. Naval Academy, until the officers training school opened in Annapolis with seven instructors, four of them from Philadelphia.

In 1889, its name was changed to the Naval Home to reflect its role as a retirement home for old salts, as they used to call retired sailors. It closed in 1976, when the Naval Home moved to Gulfport, Miss.

It was in the service of the Naval Home that Dexter came to Philadelphia.

Originally an Army artillery horse foaled in 1934, Dexter was transferred to the Navy in 1945 to haul a trash cart around the Naval Home.

Despite his lowly duties, the men — only men lived there — loved him.

“That horse was more human than animal,” Edward Pohler, chief of security at the home, told the Inquirer in 1968. “He had the run of the grounds and would come to the door of my office every day to beg for an apple or a lump of sugar.”

The chestnut gelding was retired in 1966 and sent to a farm in Exton, but that did not last long. Naval Home residents who missed him committed to paying the $50 monthly bill for his feed and care.

For two years he grazed on a three-acre field that residents dubbed Dexter Park.

But on July, 11, 1968, Dexter, who had stopped eating and was not responding to medication, died at the age of 34 in his stall with a little human intervention to make it pain-free.

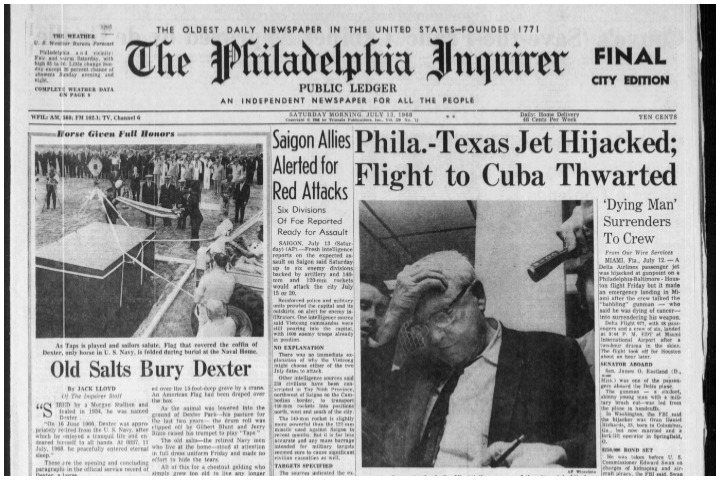

The next day, 400 people, including Navy men in dress uniform, turned out for a burial with full military honors.

Dexter was placed in a casket measuring 9 feet long, 5 feet wide, and 5 feet deep, with an American flag draped on the top. Retired Rear Adm. M.F.D. Flaherty, the home’s governor, offered final words, saying, “Dexter was no ordinary horse.”

As the casket was lowered by a crane into the 15-foot-deep grave, Gilbert Blunt rolled the drum and Jerry Rizzo played “Taps” on his trumpet. Members of the honor guard folded the flag into a triangle of white stars on a blue field and presented it to Albert A. Brenneke, a retired aviation mechanic and former farm boy from Missouri who was Dexter’s groom.

Brenneke recalled Dexter fondly, saying the horse was “very gentle and playful” and “liked to nibble on you,” according to news coverage of the funeral.

No sign exists marking Dexter’s final place.

The pasture, however, did not remain empty for long.

According to the December 1968 issue of the Navy magazine All Hands, a retired 16-year-old Fairmount Park Police horse named Tallyho took up residence at the Naval Home after Dexter’s death.

But, unlike Dexter, Tallyho, a bay gelding, was a gift to the home’s residents and did not receive an official Navy serial number.

“As was the case with Dexter, Tallyho’s only duty will be to contribute to the happiness of the men who share their retirement with him at the U.S. Naval Home,” the magazine said.

What happened to Tallyho after he went to the Naval Home is not clear.