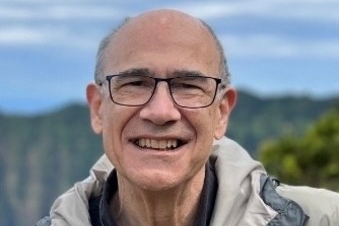

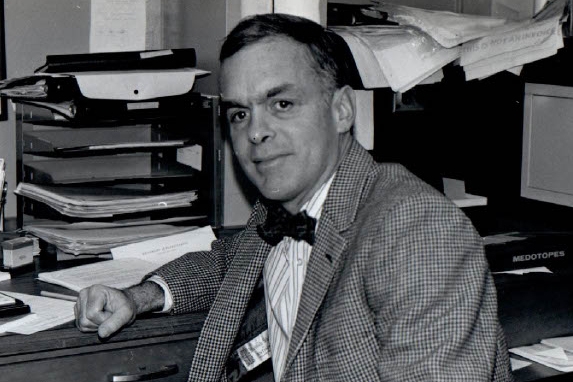

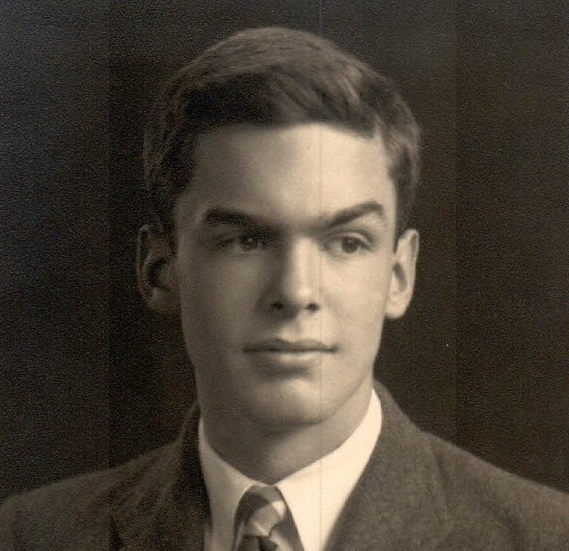

Mark Hallett, 82, of Bethesda, Md., world-renowned scientist emeritus at the Maryland-based National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, former chief of the clinical neurophysiology laboratory at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, groundbreaking researcher, prolific author, mentor, and world traveler, died Sunday, Nov. 2, of glioblastoma at his home.

Dr. Hallett was born in Philadelphia and reared in Lower Merion Township. He graduated from Harriton High School in 1961 and became a pioneering expert in movement, brain physiology, and human motor control.

He spent 38 years, from 1984 to his retirement in 2022, at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda and was clinical director and chief of the medical neurology branch of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. He and his colleagues examined the human nervous system and the brain, and their decades of research helped doctors and countless patients treat dystonia, Parkinson’s, and other neurodegenerative diseases.

“When I met him, I was in bad shape,” a former patient said on Instagram. “I’d also been told … that no one would ever figure out the source of my illness. … He and his team diagnosed me, and thereby, I’m pretty sure, saved my life”

Dr. Hallett told the Associated Press in 1992: “The more that we know about the way these cells function, the better off we are.”

He founded the NINDS’ human motor control section in 1984, cofounded the Functional Neurological Disorder Society in 2018, and served as the society’s first president. He cultivated thousands of colleagues around the world, and they called him a “giant in the field” and a “global expert” in online tributes.

Barbara Dworetzky, current president of the FNDS, said Dr. Hallett was a “brilliant scientist, visionary leader, and compassionate physician whose legacy will endure.” Former NIH colleagues called his contributions “astounding” and said: “The scope and impact of Dr. Hallett’s work transcend traditional productivity metrics.”

He chaired scientific committees and conferences, and supervised workshops for many organizations. He earned honorary degrees and clinical teaching awards, and mentored more than 150 fellows at NIH. “Our lab’s demonstration of trans-modal plasticity in humans was another milestone,” he told the NIH Record in 2023. “And, of course, I am particularly proud of the fellows that I have trained and their accomplishments.”

In a tribute, his family said those he mentored “valued his intellect, his encouragement, his kindness, and his humor.”

Dr. Hallett had planned to study astronomy at Harvard University after high school. Instead, he earned a bachelor’s degree in biology in 1965 and a medical degree at Harvard Medical School in 1969. He completed an internship at the old Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, now part of Brigham and Women’s, and joined a research program at the NIH in 1970 to fulfill his military obligation during the Vietnam War.

A fellowship in neurophysiology and biophysics at the National Institute of Mental Health sparked his interest in motor control, and he served a neurology residency at Massachusetts General Hospital in 1972 and a fellowship at the Institute of Psychiatry in London in 1974.

He returned to Brigham and Women’s in 1976 to supervise the clinical neurophysiology laboratory and rose to associate professor of neurology at Harvard. In 2019, he earned the Medal for Contribution to Neuroscience from the World Federation of Neurology, and former colleagues there recently said his work “had a lasting global impact and shaped modern clinical and research practice.”

He also studied the scientific nature of voluntary movement and free will. He wrote or cowrote more than 1,200 scientific papers on all kinds of topics, edited dozens of publications and books, and served on editorial boards.

He was past president of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology and the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society, and vice president of the American Academy of Neurology.

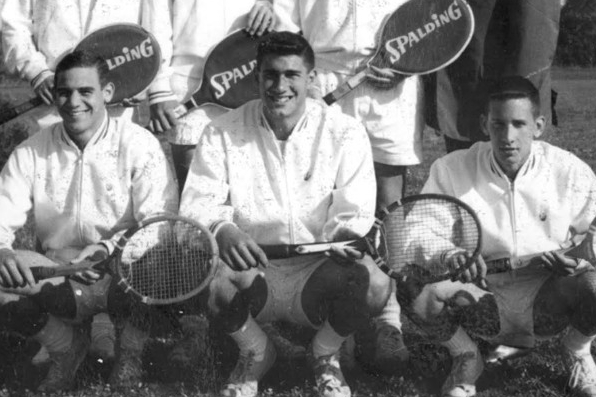

At Harriton, he was senior class president, a star tennis player, and a leading man in several theatrical shows. “The only time he disobeyed his parents,” his family said, “was when he decided to leave Philadelphia to attend Harvard College.”

Mark Hallett was born Oct. 22, 1943. The oldest of three children, he was a natural nurturer, a longtime summer camp counselor, and the winner of an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation national scholarship award in high school.

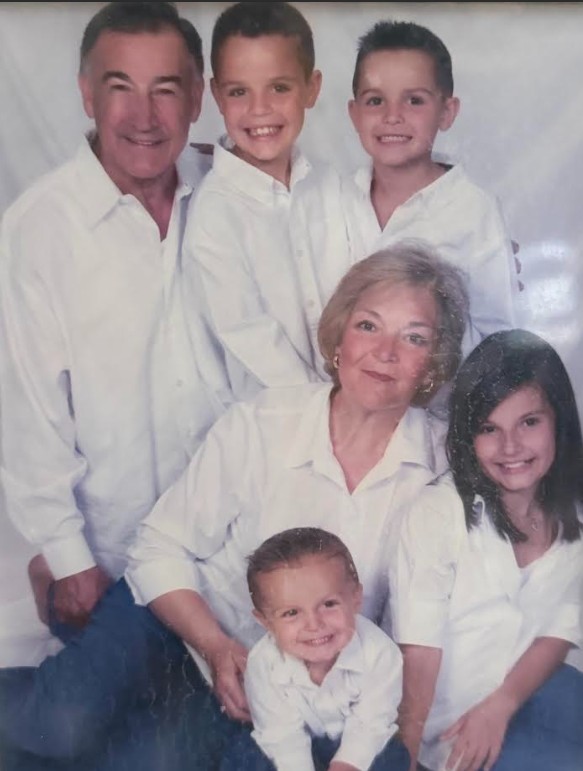

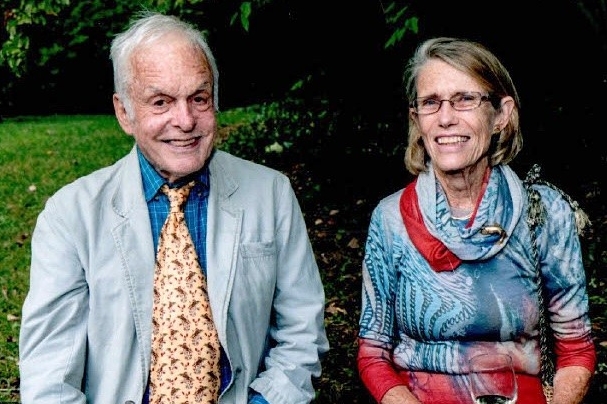

He grew up in Merion and met Judith Peller at a party in 1963. They married in 1966 and had a son, Nicholas, and a daughter, Victoria.

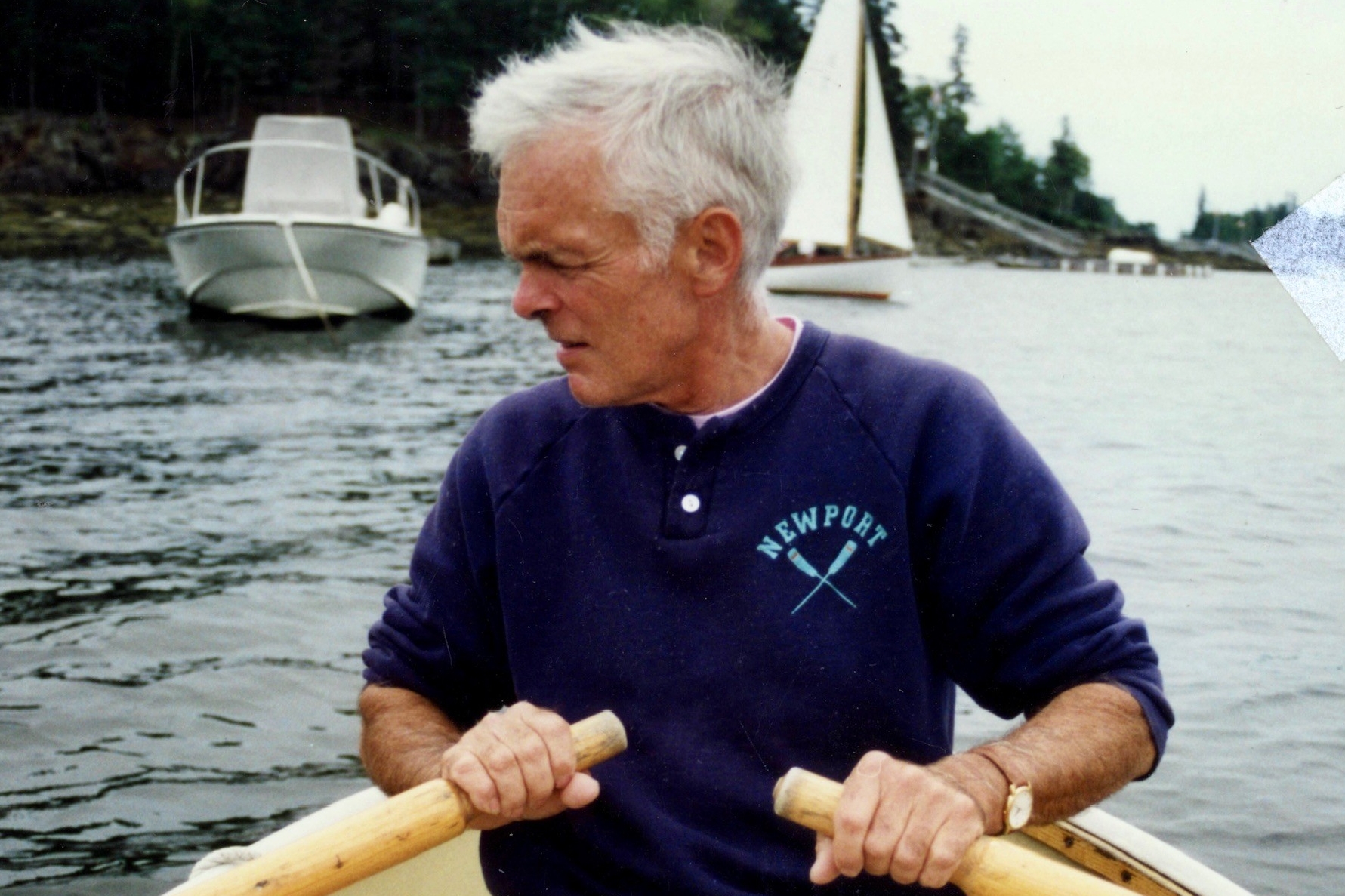

Dr. Hallett was an avid photographer and a master of the family group shot. He championed a healthy work-life balance, and his family said: “He eagerly built sand castles, skipped stones, and started pillow fights. His easy laugh was contagious.”

He enjoyed hiking, biking, jazz bands, and organizing family vacations. “He was a natural leader,” his son said, “self-assured and patient of others, with a deep sincerity and a desire to help people.”

His daughter said: “People were constantly turning to him for medical advice, and he was always willing and eager to help.”

His wife said: “He was very high energy. He brought out the best and the most in young people. He made them feel good about themselves.”

In addition to his wife and children, Dr. Hallett is survived by two granddaughters, a sister, a brother, and other relatives.

A memorial service is to be held later.

Donations in his name may be made to the Functional Neurological Disorder Society, 555 E. Wells St., Suite 1100, Milwaukee, Wis. 53202; and the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society, 555 E. Wells St., Suite 1100, Milwaukee, Wis. 53202.