In 2025, Philadelphians said goodbye to a beloved group of broadcasters, radio personalities, sports heroes, and public servants who left their mark on a city they all loved.

Some were Philly natives, including former Eagles general manager Jim Murray. Others, including beloved WMMR host Pierre Robert, were transplants who made Philly their adopted home. But all left their mark on the city and across the region.

Pierre Robert

Pierre Robert, the beloved WMMR radio host and lover of rock music, died at his Gladwyne home in October. He was 70.

A native of Northern California, Mr. Robert joined WMMR as an on-air host in 1981. He arrived in the city after his previous station, San Francisco’s KSAN, switched to an “urban cowboy” format, prompting him to make the cross-country drive to Philadelphia in a Volkswagen van.

At WMMR, Mr. Robert initially hosted on the weekends, but quickly moved to the midday slot — a position he held for more than four decades up until his death.

— Nick Vadala, Dan DeLuca

Bernie Parent

Bernie Parent, the stone-wall Flyers goalie for the consecutive Stanley Cup championship teams for the Broad Street Bullies in the 1970s, died in September. He was 80.

A Hall of Famer, Mr. Parent clinched both championships with shutouts in the final game as he blanked the Boston Bruins, 1-0, in 1974 and the Buffalo Sabres, 2-0, in 1975. Mr. Parent played 10 of his 13 NHL seasons with the Flyers and also spent a season in the World Hockey League with the Philadelphia Blazers. He retired in 1979 at 34 years old after suffering an eye injury during a game against the New York Rangers.

He grew up in Montreal and spoke French as his first language before becoming a cultlike figure at the Spectrum as cars throughout the region had “Only the Lord Saves More Than Bernie Parent” bumper stickers.

— Matt Breen

David Lynch

David Lynch, the visionary director behind such movies as Blue Velvet and The Elephant Man and the twisted TV show Twin Peaks, died in January of complications from emphysema. He was 78.

Mr. Lynch was born in Missoula, Mont., but ended up in Philadelphia to enroll at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1965 at age 19. It was here he developed an interest in filmmaking as a way to see his paintings move.

He created his first short films in Philadelphia, which he described both as “a filthy city” and “his greatest influence” as an artist. Ultimately, he moved to Los Angeles to make his first feature film, Eraserhead, though he called the film “my Philadelphia Story.”

— Rob Tornoe

Ryne Sandberg

Ryne Sandberg, the Hall of Fame second baseman who started his career with the Phillies but was traded shortly after to the Chicago Cubs in one of the city’s most regrettable trades, died in July of complications from cancer. He was 65.

Mr. Sandberg played 15 seasons in Chicago and became an icon for the Cubs, simply known as “Ryno,” after being traded there in January 1982.

He was a 10-time All-Star, won nine Gold Glove awards, and was the National League’s MVP in 1984. Mr. Sandberg was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2005 and returned to the Phillies in 2011 as a minor-league manager and, later, the big-league manager.

— Matt Breen

Bob Uecker

Bob Uecker, a former Phillies catcher who later became a Hall of Fame broadcaster for the Milwaukee Brewers and was dubbed “Mr. Baseball” by Johnny Carson for his acting roles in several movies and TV shows, died in January. He was 90.

Mr. Uecker spent just six seasons in the major league, two with the Phillies, but the talent that would make him a Hall of Fame broadcaster — wit, self-deprecation, and the timing of a stand-up comic — were evident.

His first broadcasting gig was in Atlanta, and he started calling Milwaukee Brewers games in 1971. Before that, he called Phillies games: Mr. Uecker used to sit in the bullpen at Connie Mack Stadium and deliver play-by-play commentary into a beer cup.

— Matt Breen and Rob Tornoe

Harry Donahue

Harry Donahue, 77, a longtime KYW Newsradio anchor and the play-by-play voice of Temple University men’s basketball and football for decades, died in October after a fight with cancer.

His was a voice that generations of people in Philadelphia and beyond grew up with in the mornings as they listened for announcements about snow days and, later, for a wide array of sports.

— Robert Moran

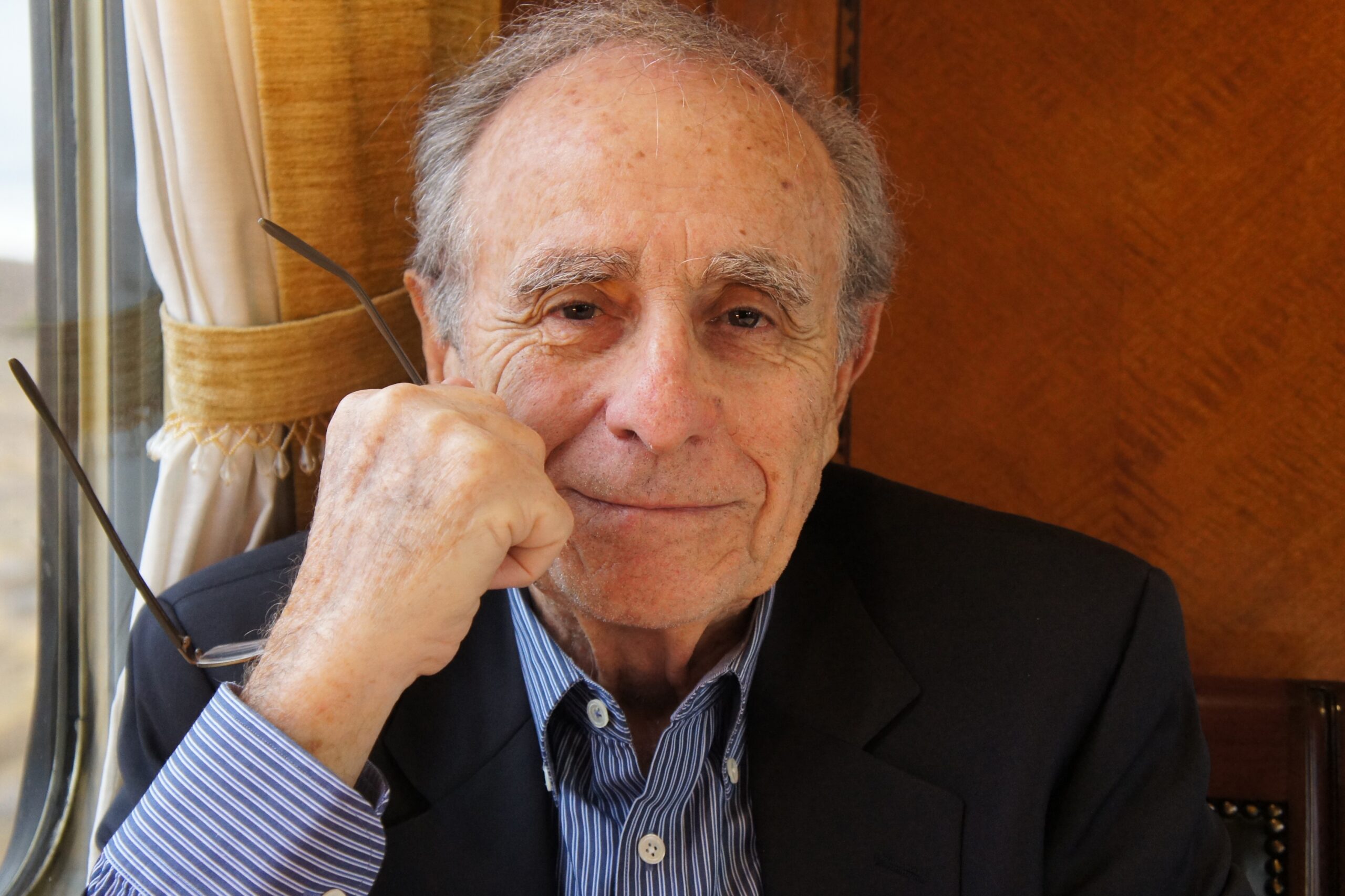

Alan Rubenstein

Alan M. Rubenstein, a retired senior judge on Bucks County Common Pleas Court and the longest-serving district attorney in Bucks County history, died in August of complications from several ailments at his home in Holland, Bucks County. He was 79.

For 50 years, from his hiring as an assistant district attorney in 1972 to his retirement as senior judge a few years ago, Judge Rubenstein represented Bucks County residents at countless crime scenes and news conferences, in courtrooms, and on committees. He served 14 years, from 1986 to 1999, as district attorney in Bucks County, longer than any DA before him, and then 23 years as a judge and senior judge on Bucks County Court.

“His impact on Bucks County will be felt for generations,” outgoing Bucks County District Attorney Jennifer Schorn said in a tribute. U.S. Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick (R., Pa.) said on Facebook: “Alan Rubenstein has never been just a name. It has stood as a symbol of justice, strength, and integrity.”

— Gary Miles

Orien Reid Nix

Orien Reid Nix, 79, of King of Prussia, retired Hall of Fame reporter for KYW-TV and WCAU-TV in Philadelphia, owner of Consumer Connection media consulting company, the first Black and female chair of the international board of the Alzheimer’s Association, former social worker, mentor, and volunteer, died in June of complications from Alzheimer’s disease.

Charismatic, telegenic, empathetic, and driven by a lifelong desire to serve, Mrs. Reid Nix worked as a consumer service and investigative TV reporter for Channels 3 and 10 in Philadelphia for 26 years, from 1973 to her retirement in 1998. She anchored consumer service segments, including the popular Market Basket Report, that affected viewers’ lives and aired investigations on healthcare issues, price gouging, fraud, and food safety concerns.

— Gary Miles

Dave Frankel

Dave Frankel, 67, a popular TV weatherman on WPVI (now 6abc) who later became a lawyer, died in February after a long battle with a neurodegenerative disease.

Mr. Frankel grew up in Monmouth County, N.J., graduated in 1979 from Dartmouth College, and was planning to attend Dickinson School of Law to become a lawyer like his father. But an internship at a local TV station in Vermont turned into a news anchor job and a broadcast career that lasted until the early 2000s.

— Robert Moran

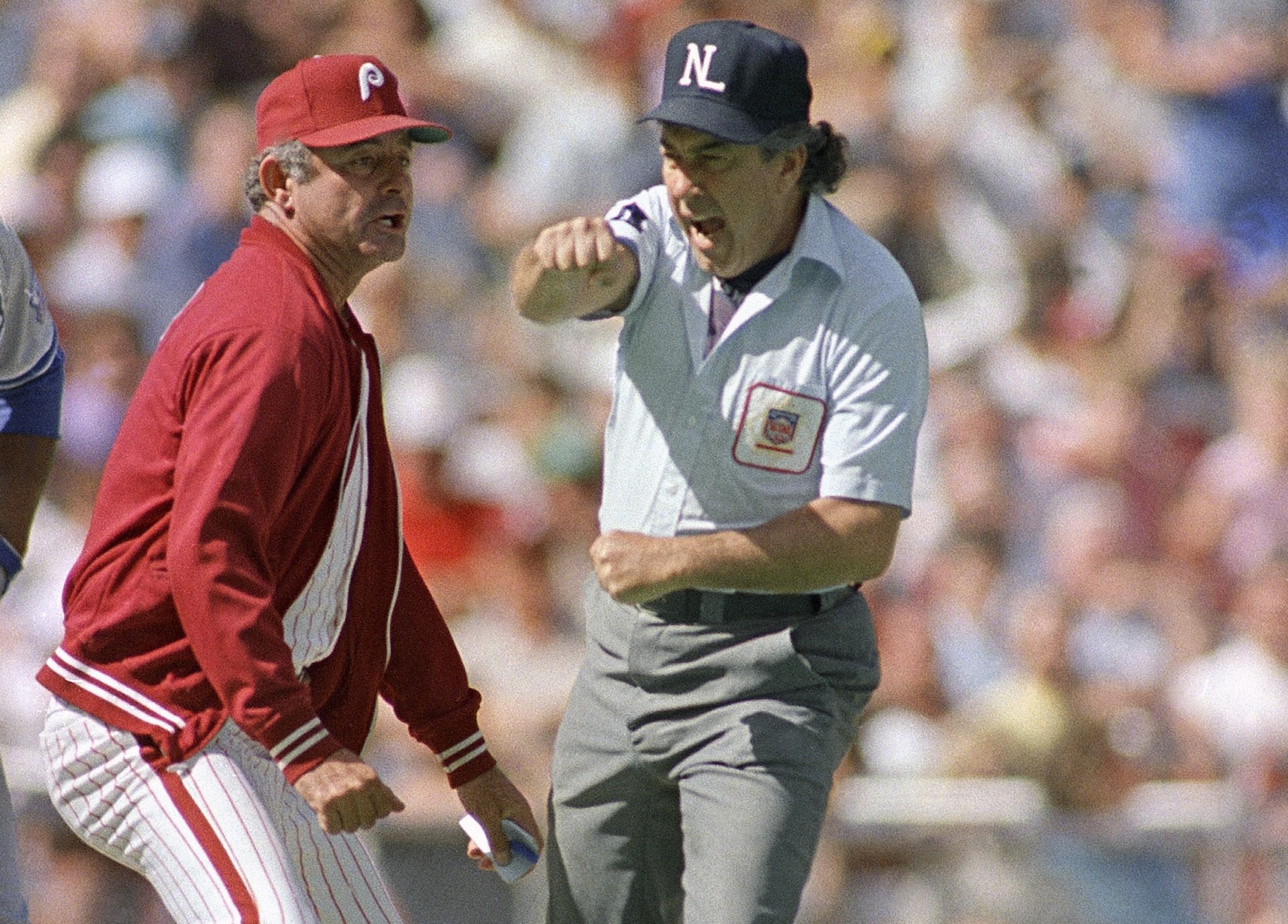

Lee Elia

Lee Elia, the Philadelphia native who managed the Phillies after coaching third base for the 1980 World Series champions and once famously ranted against the fans who sat in the bleachers of Wrigley Field, died in July. He was 87.

Mr. Elia’s baseball career spanned more than 50 seasons. He managed his hometown Phillies in 1987 and 1988 after managing the Chicago Cubs in 1982 and 1983.

After his playing career was cut shot by a knee injury, Mr. Elia joined Dallas Green’s Phillies staff before the 1980 season and was coaching third base when Manny Trillo delivered a crucial triple in the clinching game of the National League Championship Series. Mr. Elia was so excited that he bit Trillo’s arm after he slid.

— Matt Breen

Gary Graffman

Gary Graffman, a celebrated concert pianist and the former president of the Curtis Institute of Music, died in December in New York. He was 97.

The New York City-born pianist arrived at Curtis at age 7. He graduated at age 17 and played roughly 100 concerts a year between the ages of 20 and 50 before retiring from touring due to a compromised right hand. Diagnosed with focal dystonia (a neurological disorder), he went on to premiere works for the left hand by Jennifer Higdon and William Bolcom.

Mr. Graffman returned to Curtis as a teacher in 1980, became director in 1986, and was named the president of the conservatory in 1995, with a teaching studio encompassing nearly 50 students, including Yuja Wang and Lang Lang among others. He performed on numerous occasions with the Philadelphia Orchestra from 1947 to 2003.

— David Patrick Stearns

Len Stevens

Len Stevens, the cofounder of WPHL-TV (Channel 17) and a member of the Broadcast Pioneers of Philadelphia Hall of Fame, died in September of kidney failure. He was 94.

Born in Philadelphia, Mr. Stevens was a natural entrepreneur. He won an audition to be a TV announcer with Dick Clark on WFIL-TV in the 1950s, persuaded The Tonight Show and NBC to air Alpo dog food ads in the 1960s, co-owned and managed the popular Library singles club on City Avenue in the 1970s and ’80s, and later turned the nascent sale of “vertical real estate” on towers and rooftops into big business.

He and partner Aaron Katz established the Philadelphia Broadcasting Co. in 1964 and launched WPHL-TV on Sept. 17, 1965. At first, their ultrahigh frequency station, known now as PHL17, challenged the dominant very high frequency networks on a shoestring budget. But, thanks largely to Mr. Stevens’ advertising contacts and programming ideas, Channel 17 went on to air Phillies, 76ers, and Big Five college basketball games, the popular Wee Willie Webber Colorful Cartoon Club, Ultraman, and other memorable shows in the late 1960s and early ’70s.

— Gary Miles

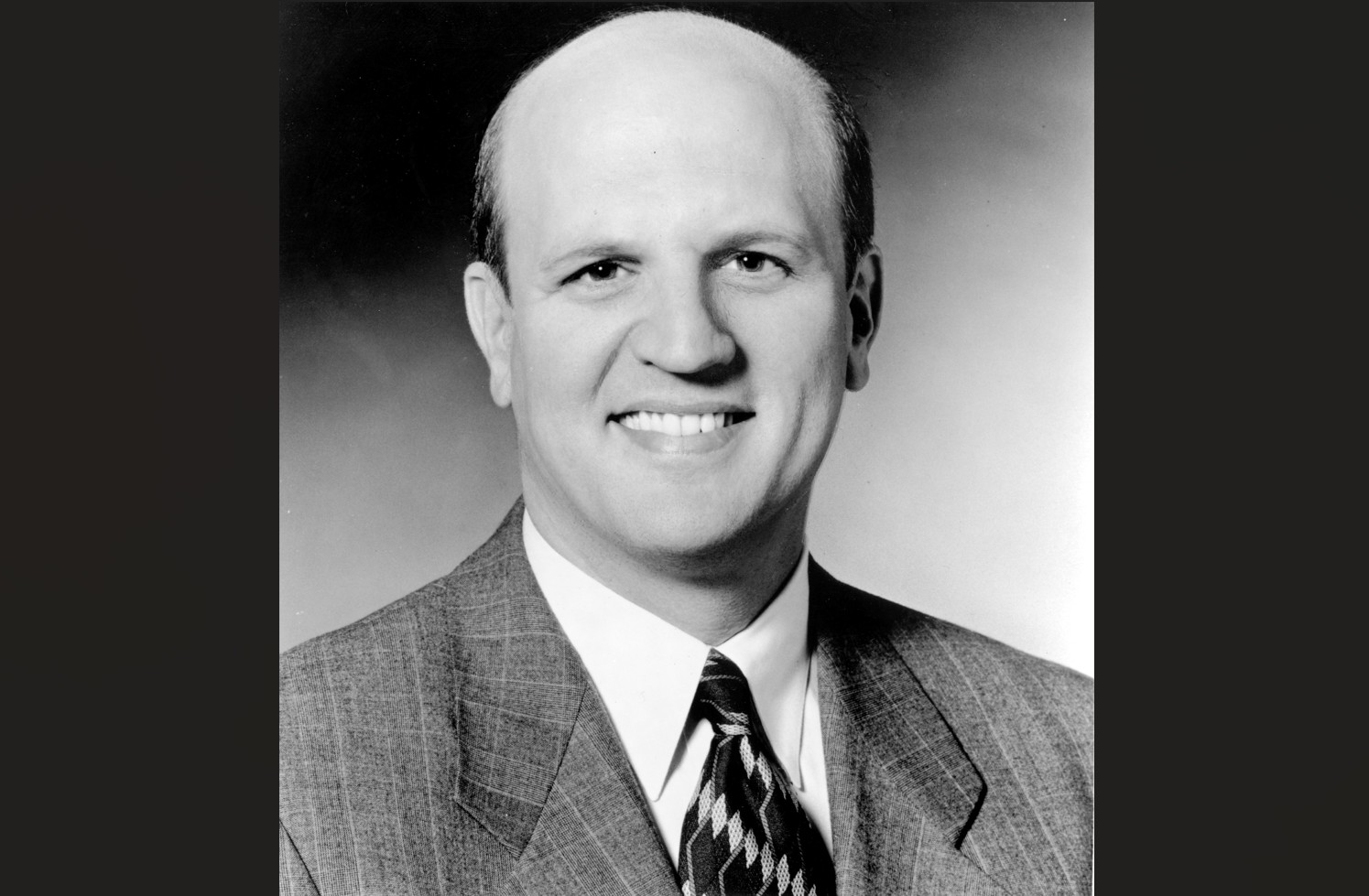

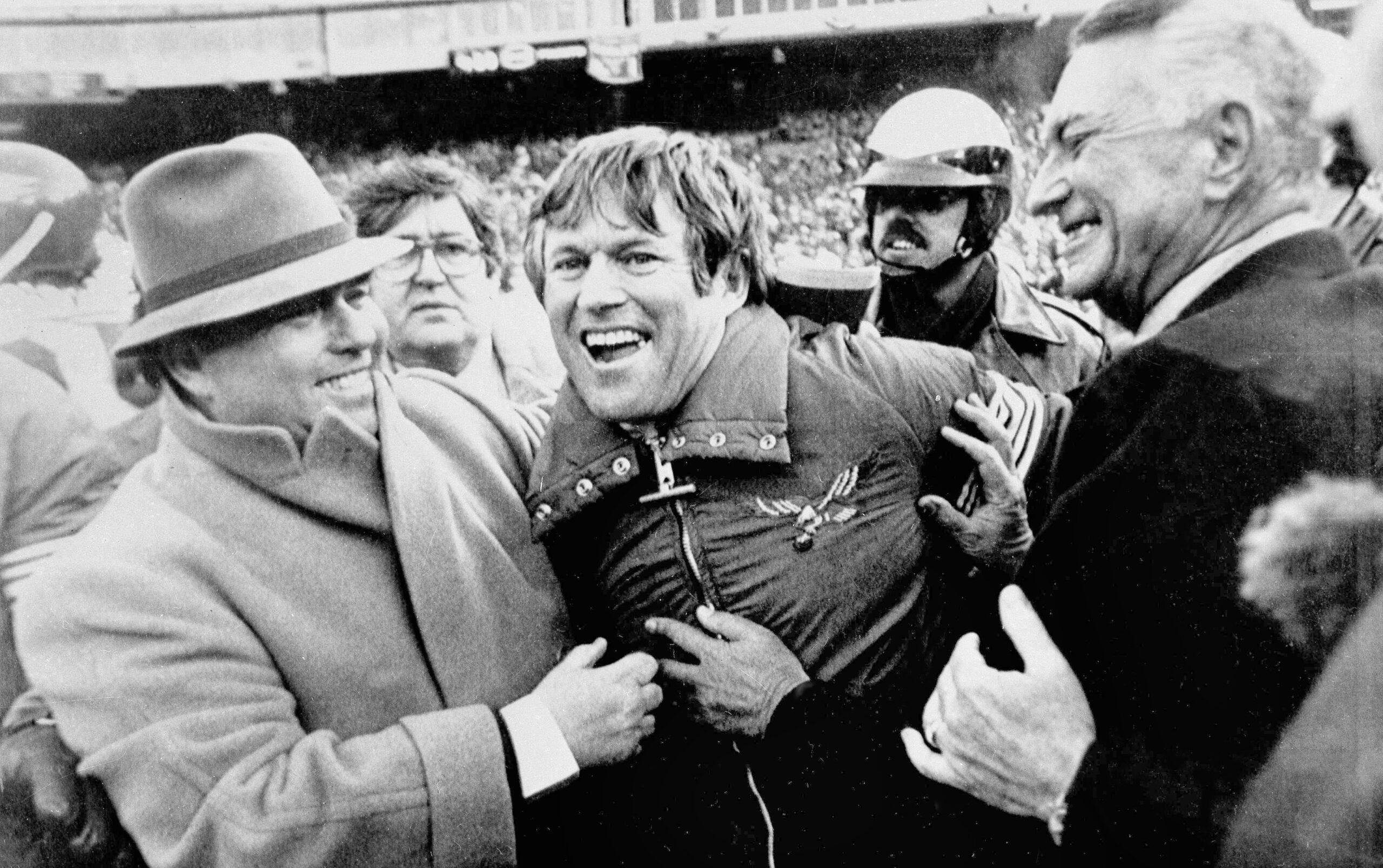

Jim Murray

Jim Murray, the former Eagles general manager who hired Dick Vermeil and helped the franchise return to prominence while also opening the first Ronald McDonald House, died in August at home in Bryn Mawr surrounded by his family. He was 87.

Mr. Murray grew up in a rowhouse on Brooklyn Street in West Philadelphia and watched the Eagles at Franklin Field. The Eagles hired him in 1969 as a publicist, and Leonard Tose, then the Eagles’ owner, named him the general manager in 1974. Mr. Murray was just 36 years old and the decision was ridiculed.

But Mr. Murray — who was known for his wit and generosity — made a series of moves to bring the Eagles back to relevance, including hiring Vermeil and acquiring players like Bill Bergey and Ron Jaworski. The Eagles made the playoffs in 1978 and reached their first Super Bowl in January 1981. The Eagles, with Murray as the GM, were finally back.

— Matt Breen

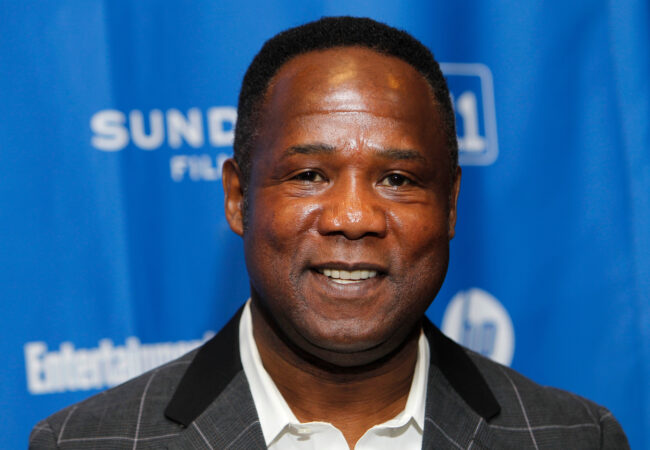

Michael Days

Michael Days, a pillar of Philadelphia journalism who championed young Black journalists and led the Daily News during its 2010 Pulitzer Prize win for investigative reporting, died in October after falling ill. He was 72.

A graduate of Roman Catholic High School in Philadelphia, Mr. Days worked at the Wall Street Journal and other newspapers before joining the Daily News as a reporter in 1986, where he ultimately became editor in 2005, the first Black person to lead the paper in its 90-year history. In 2011, Mr. Days was named managing editor of The Inquirer, where he held several management roles until he retired in October 2020.

As editor of the Daily News, Mr. Days played an essential role in the decisions that would lead to its 2010 Pulitzer Prize, including whether to move forward with a story about a Philadelphia Police Department narcotics officer that a company lawyer said stood a good chance of getting them sued.

“He said, ‘I trust my reporters, I believe in my reporters, and we’re running with it,’” recounted Inquirer senior health reporter Wendy Ruderman, who reported the piece with colleague Barbara Laker. That story revealed a deep dysfunction within the police department, Ruderman said, and led to the newspaper’s 2010 Pulitzer Prize win.

— Brett Sholtis

Tom McCarthy

Tom McCarthy, an award-winning theater, film, and TV actor, longtime president of the local chapter of the Screen Actors Guild, former theater company board member, mentor, and veteran, died in May of complications from Parkinson’s disease at his home in Sea Isle City. He was 88.

The Overbrook native quit his job as a bartender in 1965, sharpened his acting skills for a decade at Hedgerow Theatre Company in Rose Valley and other local venues, and, at 42, went on to earn memorable roles in major movies and TV shows.

In the 1980s, he played a police officer with John Travolta in the movie Blow Out and a gardener with Andrew McCarthy in Mannequin. In 1998, he was a witness with Denzel Washington in Fallen. In 2011, he was a small-town mayor with Lea Thompson in Mayor Cupcake. Over the course of his career, Mr. McCarthy acted with Zsa Zsa Gabor, Harrison Ford, Kristin Scott Thomas, Cloris Leachman, Robert Redford, Donald Sutherland, John Goodman, and other big stars.

— Gary Miles

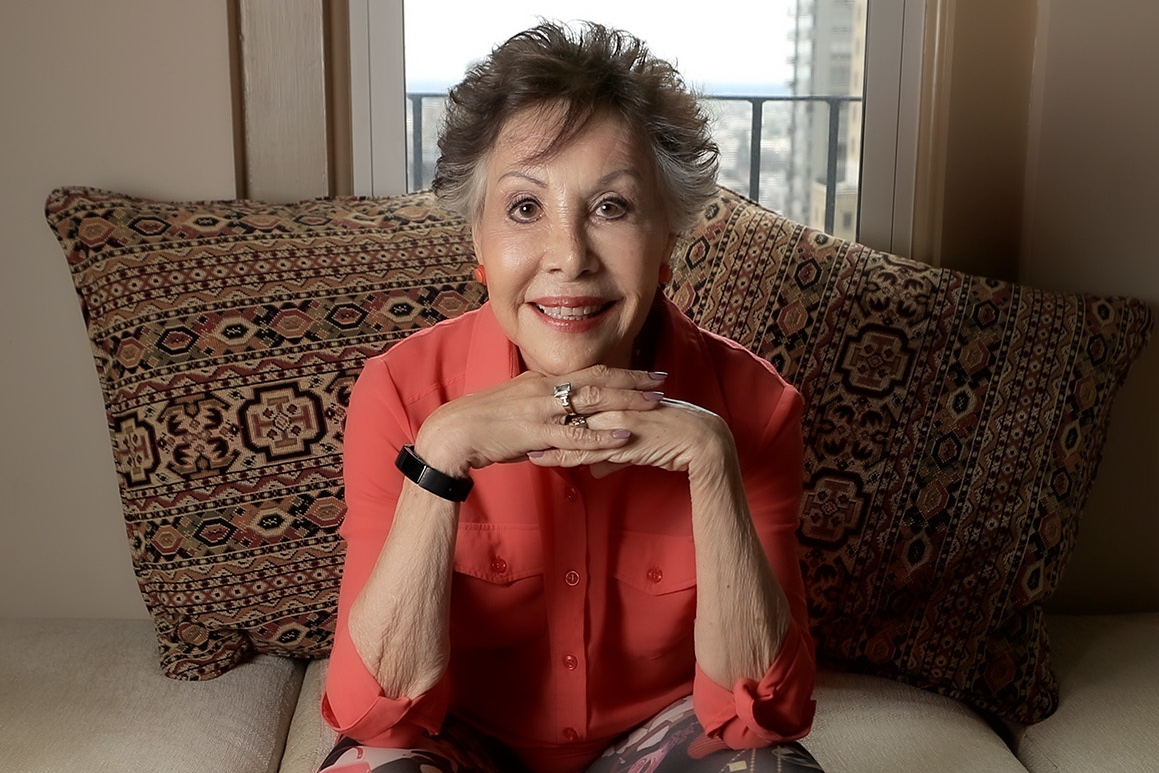

Carol Saline

Carol Saline, a longtime senior writer at Philadelphia Magazine, the best-selling author of Sisters, Mothers & Daughters, and Best Friends, and a prolific broadcaster, died in August of acute myeloid leukemia. She was 86.

On TV, she hosted a cooking show and a talk show, was a panelist on a local public affairs program, and guested on the Oprah Winfrey Show, Inside Edition, Good Morning America, and other national shows. On radio, she hosted the Carol Saline Show on WDVT-AM.

In June, she wrote to The Inquirer, saying: “I am contacting you because I am entering hospice care and will likely die in the next few weeks. … I wanted you to know me, not only my accomplishments but who I am as a person.

“I want to go out,” she ended her email, “with a glass of Champagne in one hand, a balloon in the other, singing (off key) ‘Whoopee! It’s been a great ride!’”

— Gary Miles

Richard Wernick

Richard Wernick, a Pulitzer Prize-winning composer, acclaimed conductor, and retired Irving Fine Professor of Music at the University of Pennsylvania, died in April 25 of age-associated decline at his Haverford home. He was 91.

Professor Wernick was prolific and celebrated as a composer. He wrote hundreds of scores over six decades and appeared on more than a dozen records, and his Visions of Terror and Wonder for a mezzo-soprano and orchestra won the 1977 Pulitzer Prize for music. In 1991, his String Quartet No. 4 made him the first two-time winner of the Kennedy Center’s Friedheim Award for new American music.

“Wernick’s orchestral music has power and brilliance, an emphasis on register, space, and scale,” Lesley Valdes, former Inquirer classical music critic, said in 1990.

— Gary Miles

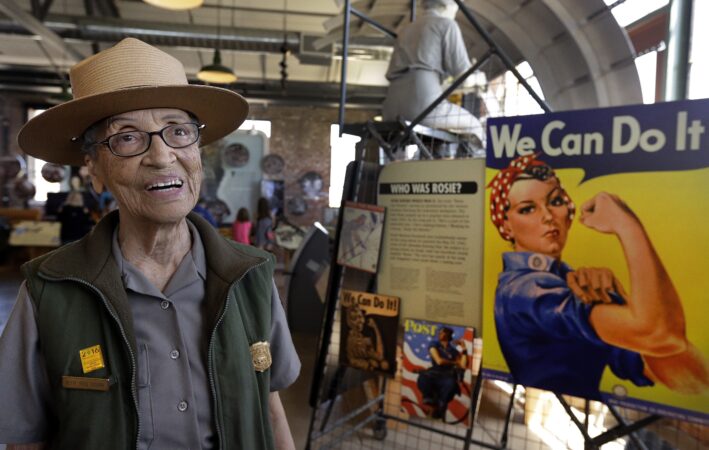

Dorie Lenz

Dorie Lenz, a pioneering TV broadcaster and the longtime director of public affairs for WPHL-TV (Channel 17), died in January of age-associated ailments at her home in New York. She was 101.

A Philadelphia native, Ms. Lenz broke into TV as a 10-year-old in a local children’s show and spent 30 years, from 1970 to 2000, as director of public affairs and a program host at Channel 17, now PHL17. She specialized in detailed public service campaigns on hot-button social issues and earned two Emmys in 1988 for her program Caring for the Frail Elderly.

Ms. Lenz interviewed newsmakers of all kinds on the public affairs programs Delaware Valley Forum, New Jersey Forum, and Community Close Up. Viewers and TV insiders hailed her as a champion and watchdog for the community. She also talked to Phillies players before games in the 1970s on her 10-minute Dorie Lenz Show.

— Gary Miles

Jay Sigel

Jay Sigel, one of the winningest amateur golfers of all time and an eight-time PGA senior tour champion, died in April of complications from pancreatic cancer. He was 81.

For more than 40 years, from 1961, when he won the International Jaycee Junior Golf Tournament as an 18-year-old, to 2003, when he captured the Bayer Advantage Celebrity Pro-Am title at 60, the Berwyn native was one of the winningest amateur and senior golfers in the world. Mr. Sigel won consecutive U.S. Amateur titles in 1982 and ’83 and three U.S. Mid-Amateur championships between 1983 and ’87, and remains the only golfer to win the amateur and mid-amateur titles in the same year.

He won the Pennsylvania Amateur Championship 11 times, five straight from 1972 to ’76, and the Pennsylvania Open Championship for pros and amateurs four times. He also won the 1979 British Amateur Championship and, between 1975 and 1999, played for the U.S. team in a record nine Walker Cup tournaments against Britain and Ireland.

— Gary Miles

Mark Frisby

Mark Frisby, the former publisher of the Daily News and associate publisher of The Inquirer, died in September of takayasu arteritis, an inflammatory disease, at his home in Gloucester County. He was 64.

Mr. Frisby joined The Inquirer and Daily News in November 2006 as executive vice president of production, labor, and purchasing. He was recruited from the Courier-Post by then-publisher Brian Tierney, and he went on to serve as publisher of the Daily News from 2007 to 2016 and associate publisher for operations of The Inquirer and Daily News from 2014 to his retirement in 2016.

Mr. Frisby was one of the highest-ranking Black executives in the company’s history, and he told the Daily News in 2006 that “local ownership over here was the big attraction for me.” Michael Days, then the Daily News editor, said in 2007: “This cat is really the real deal.”

— Gary Miles

Leon Bates

Leon Bates, a concert pianist whose musical authority and far-reaching versatility took him to the world’s greatest concert halls, died in November after a seven-year decline from Parkinson’s disease. He was 76.

The career of Mr. Bates, a leading figure in the generation of Black pianists who followed the early-1960s breakthrough of Andre Watts, encompassed Ravel, Gershwin, and Bartok over 10 concerts with the Philadelphia Orchestra between 1970 and 2002. He played three recitals with Philadelphia Chamber Music Society and taught master classes at Temple University, where he also gave recitals at the Temple Performing Arts Center.

In his WRTI-FM radio show, titled Notes on Philadelphia, during the 1990s, Mr. Bates was what Charles Abramovic, chair of keyboard studies at Temple University, described as “beautifully articulate and a wonderful interviewer. The warmth of personality came out. He was such a natural with that.”

— David Patrick Stearns

Lacy McCrary

Lacy McCrary, a former Inquirer reporter who won a Pulitzer Prize at the Akron Beacon Journal, died in March of Alzheimer’s disease at his home in Colorado Springs, Colo. He was 91.

Mr. McCrary, a Morrisville, Bucks County native, won the 1971 Pulitzer Prize in local general or spot news reporting as part of the Beacon Journal’s coverage of the May 4, 1970, student protest killings at Kent State University.

He joined The Inquirer in 1973 and covered the courts, politics, and news of all sorts until his retirement in 2000. He notably wrote about unhealthy conditions and fire hazards in Pennsylvania and New Jersey boardinghouses in the late 1970s and early ’80s, and those reports earned public acclaim and resulted in new regulations to correct deadly oversights.

— Gary Miles

Roberta Fallon

Roberta Fallon, 76, cofounder, editor, and longtime executive director of the online Artblog and adjunct professor at St. Joseph’s University, died in December at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital of injuries she suffered after being hit by a car. She was 76.

Described by family and friends as empathetic, energetic, and creative, Ms. Fallon and fellow artist Libby Rosof cofounded Artblog in 2003. For nearly 22 years, until the blog became inactive in June, Ms. Fallon posted commentary, stories, interviews, reviews, videos, podcasts, and other content that chronicled the eclectic art world in Philadelphia.

— Gary Miles

Benita Valente

Benita Valente, a revered lyric soprano whose voice thrilled listeners with its purity and seeming effortlessness, died in October at home in Philadelphia. She was 91.

In a remarkable four-decade career, Ms. Valente appeared on the opera stage, in chamber music, and with orchestras. In the intimate genre of lieder — especially songs by Schubert and Brahms — she was considered one of America’s great recitalists.

— Peter Dobrin