For years, Philadelphia, like many American cities, grappled with historic levels of violence brought on by the upheaval of the pandemic. Today, a very different story is unfolding.

Violent crime in Philadelphia has declined sharply and sustainably, and much of that progress is owed to the extraordinary work and unwavering commitment of the men and women of the Philadelphia Police Department.

Homicides are down again this year, by roughly 15% to 18% compared with last year, putting the city on pace for its lowest total since the 1960s. Shootings, both fatal and nonfatal, have fallen to levels not seen in more than a decade.

At the same time, homicide clearance rates have reached historic highs, bringing accountability, answers, and a measure of justice to families who have suffered unimaginable loss.

These results did not happen by chance. They are the product of relentless professionalism, data-driven policing, and deep engagement with the communities officers serve.

Behind every statistic is a patrol officer, detective, analyst, supervisor, or civilian professional who showed up day after day, determined to protect this city. Lives have been saved, neighborhoods strengthened, and trust rebuilt because of their work.

Philadelphia is safer today than it has been in a generation, and that progress deserves recognition.

Changing threats

But public safety is not defined solely by addressing violent crime. Some of the most damaging threats we face today are quieter, more personal, and increasingly digital.

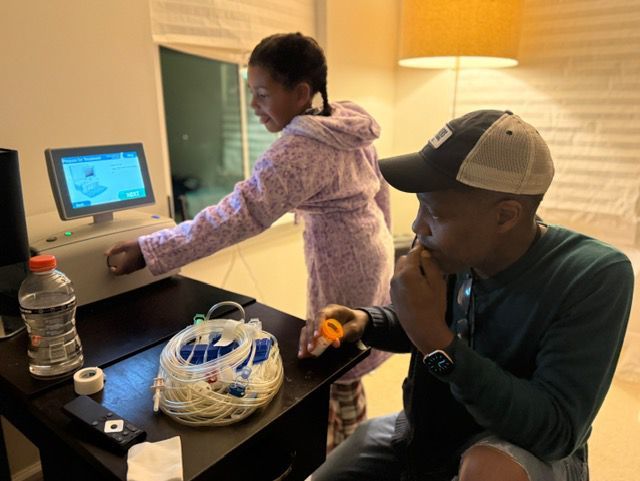

Across Philadelphia and the surrounding region, criminals continue to target the most vulnerable among us. Elderly residents are being deceived out of their life savings through increasingly sophisticated fraud schemes. Young people are being exploited through sextortion, often by offenders operating overseas who use fear, manipulation, and anonymity to cause devastating harm. Businesses of every size are facing ransomware attacks that can cripple operations, disrupt critical services, and threaten livelihoods.

At the same time, our business community and world-class academic institutions face persistent threats from nation-state actors seeking to steal intellectual property, sensitive data, and cutting-edge research. These efforts target innovation, economic competitiveness, and national security itself, and they often unfold silently over months or years before being discovered.

Such crimes leave deep scars. They are often underreported, emotionally devastating, and constantly evolving. Addressing them requires persistence, adaptability, and a willingness to confront threats that do not always fit traditional definitions of crime.

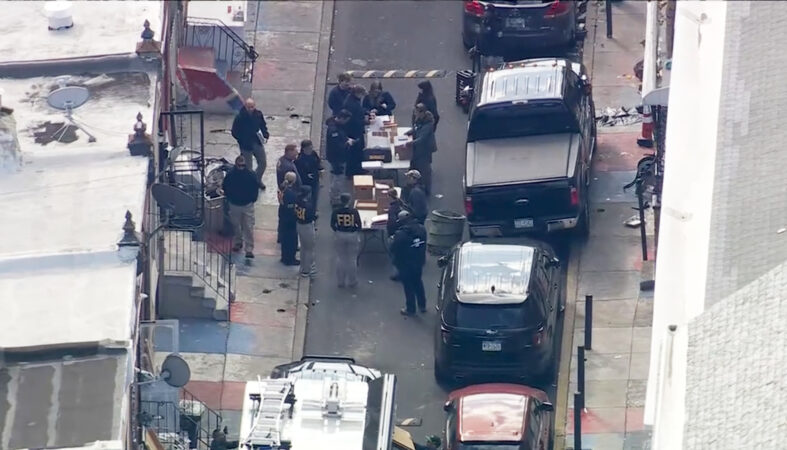

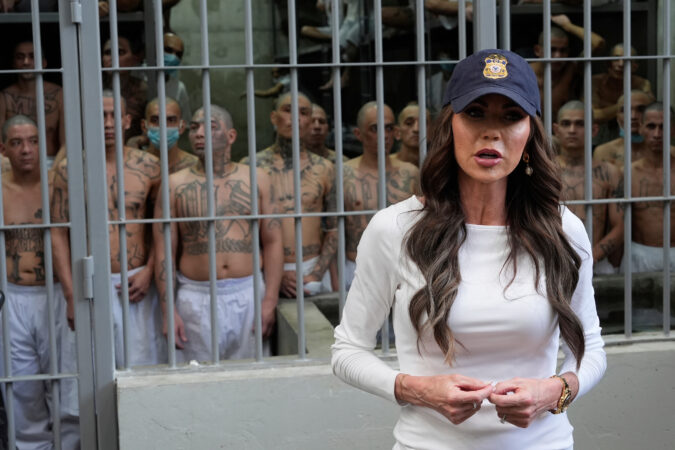

Every day, the men and women of the FBI show up with a clear purpose: to protect people and hold perpetrators accountable. Our agents, intelligence analysts, and professional staff work tirelessly to identify offenders, dismantle criminal networks, prevent acts of terrorism, disrupt foreign intelligence threats, and bring those responsible to justice, whether they operate across the street or across the world.

But enforcement alone is not enough. Preventing harm before it occurs is one of the most powerful tools we have.

That is why outreach and education are central to our mission.

Building partnerships

Through partnerships with schools, senior centers, businesses, universities, and community organizations, we work to raise awareness, share intelligence, and empower people to recognize threats early. Helping a senior avoid a scam, a teenager seek help before harm escalates, or an institution protect sensitive research can be just as impactful as an arrest.

None of this work happens in isolation. The progress Philadelphia has made, both in reducing violent crime and in confronting complex threats like fraud, sextortion, ransomware, and foreign intellectual property theft, is rooted in strong partnerships. Federal, state, and local law enforcement, prosecutors, private-sector leaders, and academic institutions are aligned around a shared responsibility to keep this city safe.

Those partnerships will be more important than ever as Philadelphia prepares for a historic year in 2026. With global events, national celebrations, and millions of visitors expected, success will depend on seamless coordination, shared intelligence, and a unified approach to prevention and preparedness.

We are ready because we have built this foundation together.

Philadelphia’s progress is real. The challenges ahead are serious. And by continuing to work side by side, guided by intelligence, driven by prevention, and grounded in partnership, we will keep this city safe in 2026 and beyond.

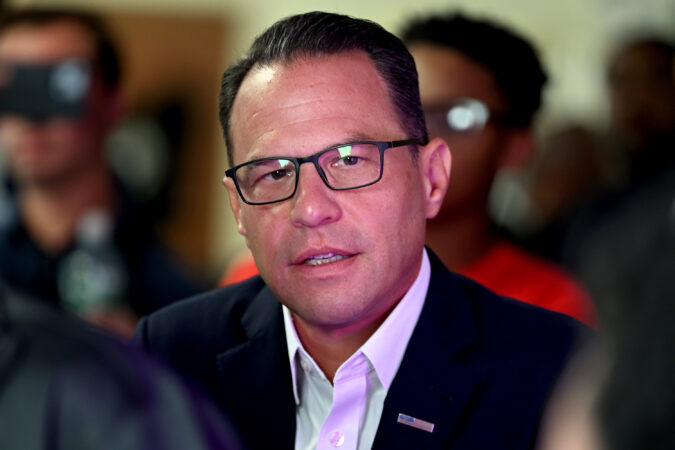

Wayne A. Jacobs is the special agent in charge of the FBI’s Philadelphia Field Office, a position he’s held since November 2023.