By the early 1980s, Philadelphia’s Chinatown was more than 100 years old and struggling to survive.

Boxed in by the Vine Street Expressway, Market Street, the old Metropolitan Hospital, and the Convention Center, the neighborhood had no space to grow and no way to shine.

In 1982, executive director of the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corp. Cecilia Moy Yep — well-known for stopping the razing of Holy Redeemer Chinese Catholic Church — and architect James Guo went to China and formalized a Sister City agreement between Philadelphia and the northern Chinese city of Tianjin.

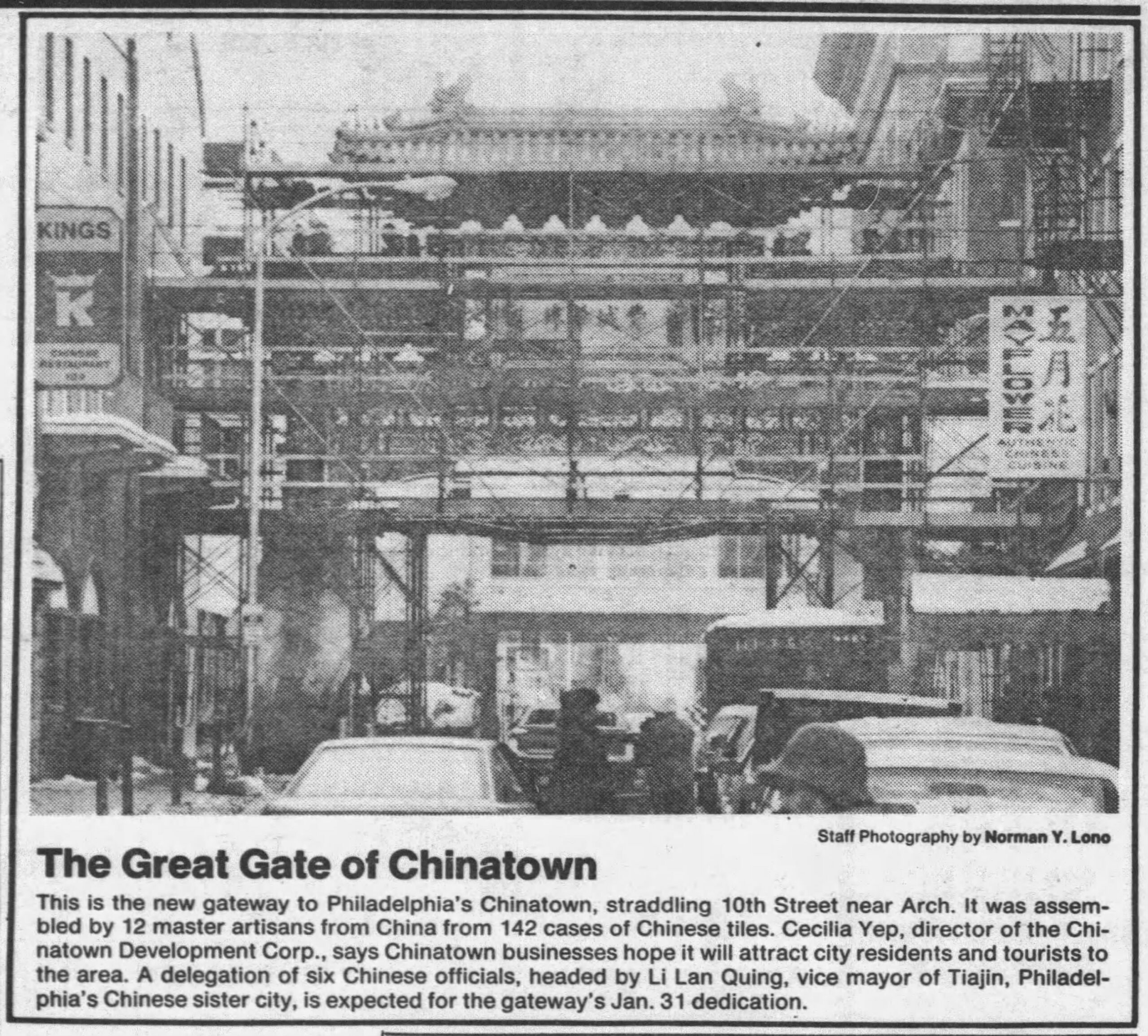

Plans for an ornate Chinatown entryway followed. In October 1983, 12 artisans from Tianjin and Beijing arrived in Philadelphia and spent three months building a 88-ton, 40-foot-tall gate with wood, tiles, stone bases, and a special material that incorporates pig’s blood that’s painted over the wood to stop it from fading and shipped from China.

The San Francisco Chinatown Gate had been built in the 1970s and Boston’s was finished in 1982. But Philly’s Friendship Gate, erected at the intersection of 10th and Arch Streets, is the first Chinese American archway built with materials from Asia, making Philly’s gate the “authentic” deal.

That first authentic Chinese gate built in America will be feted Saturday in Chinatown at the Crane Community Center, this week’s Philadelphia Historic District’s Firstival celebration. Firstivals are a year’s worth of parties marking America’s 250th birthday, noting events that happened in Philadelphia before anywhere else in America and often the world.

The Friendship Gate, built in traditional Qing Dynasty style, cost more than $200,000 in city funds to construct. The ribbon-cutting ceremony in January 1984 featured the ceremonial dance of the Chinese lion known as Wushi, performed for good luck and to chase away evil spirits, and speeches from city officials in both Mandarin and English.

“We needed something to attract people into Chinatown,” Yep told The Inquirer, shortly after its Jan. 31, 1984, unveiling.

Its mud brown roof, square beams, dazzling green and gold patterns, and birds and dragons outlining the sky, mark the point where Center City meets the Chinese community.

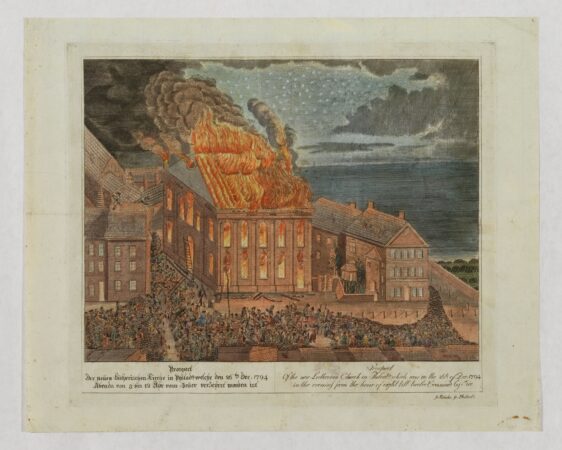

Five months after the Friendship Gate was completed, a fire — then the biggest in Center City history — raced north from 10th and Filbert Streets and stopped, almost magically, at the Friendship Gate.

“I am so glad the gate was not damaged,” T.T. Chang, then president of the Chinese Cultural Society — and unofficial mayor of Chinatown — told The Inquirer.

In September 1984, the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation introduced the first official postcard with the Friendship Gate’s image, marking it as a bona fide tourist attraction. (Although its real goal was to raise $55,000 to pay for the portion of the gate the city refused to pay for.)

In 2008, in its 24th year as a recognized Philadelphia monument, the gate was rededicated after a yearlong, $200,000 renovation project.

Chinatown has had its challenges over the last decades, but it continues to thrive. For 41 years, the Friendship Gate has stood proudly, a welcoming archway rooted in resistance.

This week’s Firstival is Saturday, Feb. 21, 11 a.m.-1 p.m., Crane Community Center, 1001 Vine St. The Inquirer will highlight a “first” from the Philadelphia Historic District’s 52 Weeks of Firsts program every week. A “52 Weeks of Firsts” podcast, produced by All That’s Good Productions, drops every Tuesday.