When Justin Burkhardt heard that his neighborhood grocery store was closing, just months after it had opened, he felt a pang of sadness.

The emotion surprised him, he said, because that store was the Northern Liberties Amazon Fresh.

“Amazon is a big corporation, but [with] the people that worked there [in Northern Liberties] and the fact that it was so affordable, it actually started to feel like a neighborhood grocery store,” said Burkhardt, 40, a public relations professional, who added that he is not a fan of Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s billionaire owner.

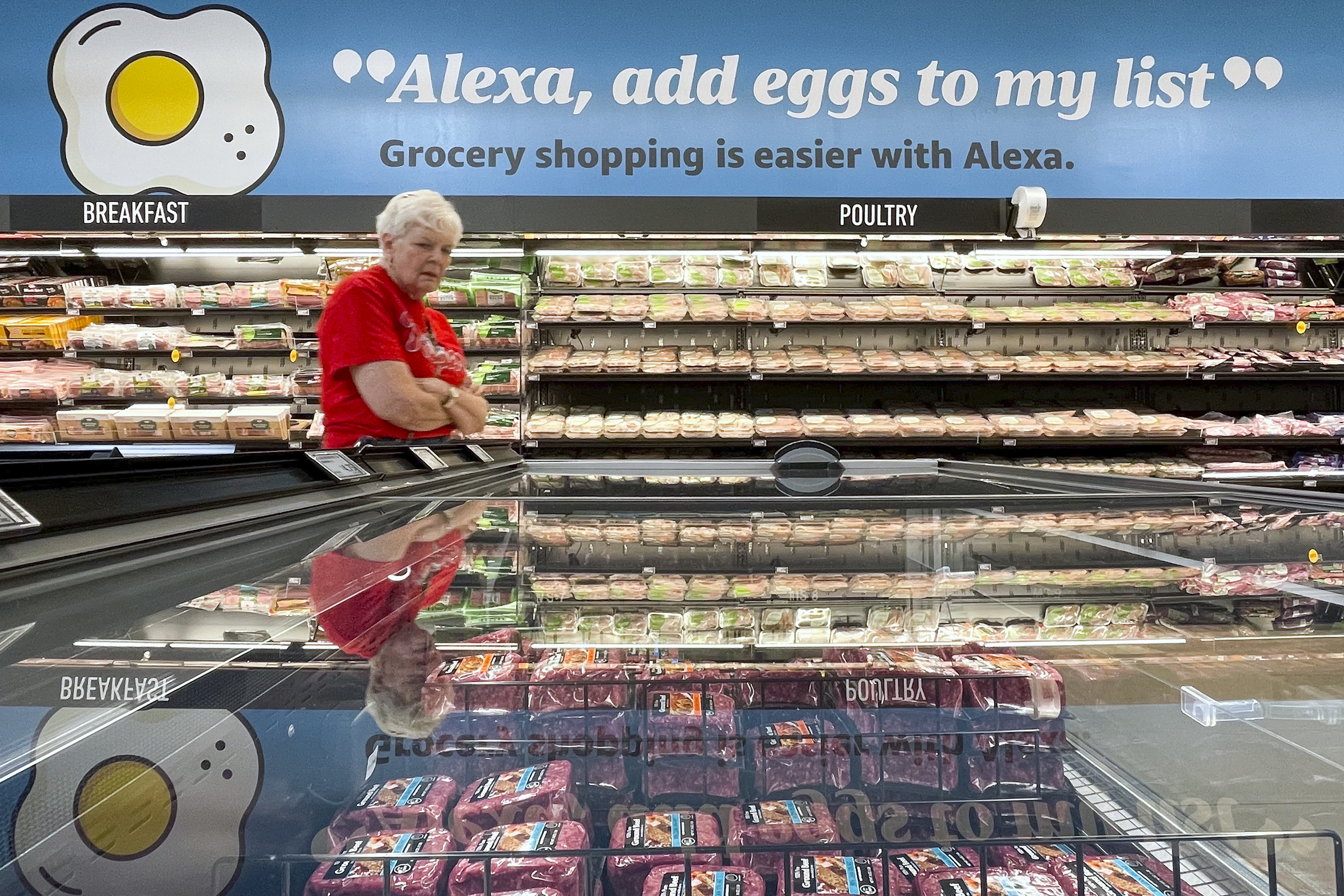

The e-commerce giant announced last month that it was closing all physical Amazon Fresh stores as it expands its Whole Foods footprint. In the Philadelphia area, the shuttering of six Amazon Fresh locations resulted in nearly 1,000 workers being laid off. Local customers said their stores closed days after the company’s announcement.

“I don’t feel bad for Amazon,” said Burkhardt, who spent about $200 a week at Amazon Fresh. “I feel bad for the workers. … I feel bad for the community members.”

Burkhardt said he and his wife have been forced to return to their old grocery routine: Driving 20 minutes to the Cherry Hill Wegmans, where they feel the prices are cheaper than their nearby options in the city.

In Philadelphia and its suburbs, many former Amazon Fresh customers are similarly saddened by the closure of neighborhood stores where they had developed connections with helpful workers. Several said they are most upset about the effects on their budgets amid recent years’ rise in grocery prices.

“I wasn’t happy about it closing for the simple fact that it was much cheaper to shop there,” said Brandon Girardi, a 30-year-old truck driver from Levittown (who quit a job delivering packages for Amazon a few years ago). Girardi said his family’s weekly $138 grocery haul from the Langhorne Amazon Fresh would have cost at least $200 at other local stores.

At the Amazon Fresh in Broomall, “they had a lot of organic stuff for a quarter of the price of what Giant or Acme has,” said Nicoletta O’Rangers, a 58-year-old hairstylist who shopped there for the past couple years. “They were like the same things that were in Whole Foods but cheaper than Whole Foods.”

She paused, then added: “Maybe that’s why they didn’t last.”

In response to questions from The Inquirer, an Amazon spokesperson referred to the company’s original announcement. In that statement, executives wrote: “While we’ve seen encouraging signals in our Amazon-branded physical grocery stores, we haven’t yet created a truly distinctive customer experience with the right economic model needed for large-scale expansion.”

What makes a Philly shopper loyal to a grocery store?

Former Amazon Fresh customers say they’re now shopping around for a new grocery store and assessing what makes them loyal to one supermarket over another.

Last week, one of those customers, Andrea “Andy” Furlani, drove from her Newtown Square home to Aldi in King of Prussia. The drive is about an hour round trip, she said, but the prices are lower than at some other stores. Her five-person, three-dog household tries to stick to a $1,200 monthly grocery budget.

As she drove to Aldi, she said, she’d already been alerted that the store was out of several items she had ordered for pickup. That’s an issue Furlani said she seldom encountered at the Amazon Fresh in Broomall, to which she had become “very loyal” in recent years.

“It was small, well-stocked,” said Furlani, 43, who works in legal compliance. “I don’t like to go into like a Giant and have a billion options. Sometimes less is more. And the staff was awesome,” often actively stocking shelves and unafraid to make eye contact with customers.

“Time is valuable to me,” Furlani said. At Amazon Fresh, “you could get in and out of there quickly.”

Girardi, in Levittown, said he is deciding between Giant and Redner’s now that Amazon Fresh is gone. The most cost-effective store would likely win out, he said, but product quality and convenience are important considerations, too.

“We used to do Aldi, but Amazon Fresh had fresher produce,” Girardi said. “I used to have a real good connection with Walmart because my mom used to work there. But I don’t see myself going all the way to Tullytown just to go grocery shopping.”

Susan and Michael Kitt, of Newtown Square, shopped at the Broomall Amazon Fresh for certain items, such as $1.19 gallons of distilled water for their humidifiers and Amy’s frozen dinners that were dollars cheaper than at other stores.

But Giant is the couple’s mainstay. They said they like its wide selection, as well as its coupons and specials that save them money.

“I got suckered by Giant on their marketing with the Giant-points-for-gas discounts. I figured if I’m going to a store I may as well get something out of it,” said Michael Kitt, a 70-year-old business owner who has saved as much as $2-per-gallon with his Giant rewards. “I really at the time didn’t see that much of a difference between the stores.”

How Whole Foods might fare in Amazon Fresh shells

If any of these local Amazon Fresh stores were to become a Whole Foods, several customers said they’d be unlikely to return, at least not on a regular basis.

Amazon said last month that it plans to turn some Amazon Fresh stores into Whole Foods Markets, but did not specify which locations might be converted.

Amazon bought Whole Foods in 2017. The organic grocer is sometimes referred to as “Whole Paycheck,” but the company has been working to shed that reputation for more than a decade.

Some Philly-area consumers, however, said Whole Foods prices would likely be a deterrent.

Natoya Brown-Baker, 42, of Overbrook, said she found the Northern Liberties Amazon Fresh “soulless,” and she didn’t “want to give Jeff Bezos any more money.” But the prices at Amazon Fresh were so low, she said, that she couldn’t resist shopping there sometimes.

Brown-Baker, who works in health equity, said she came to appreciate that it represented an affordable, walkable option for many in the neighborhood, including her parents, who are on a fixed income.

If a Whole Foods replaces the store at Sixth and Spring Garden Streets, which was under construction for years, Brown-Baker said the area would be “back at square one.”

Burkhardt, who also lives in the neighborhood, noted that Northern Liberties has a mix of fancy new apartment complexes and low-income housing.

“The grocery store should be for everyone,” he said. Whole Foods “doesn’t feel like it’s for the neighborhood. It feels like it’s for a certain class of people.”