A high-stakes fight is brewing between President Donald Trump’s administration and states such as Pennsylvania and New Jersey over the regulation of prediction markets, the online platforms that allow users to wager on everything from sports and elections to the weather.

States that have legalized sports betting in recent years say prediction markets amount to unauthorized gambling, putting consumers at risk and threatening tax revenues generated by regulated entities like casinos.

But the Trump administration this week said the federal government was the appropriate regulator, siding with the industry’s argument that the markets’ “event contracts” are financial derivatives that allow investors to hedge against risks.

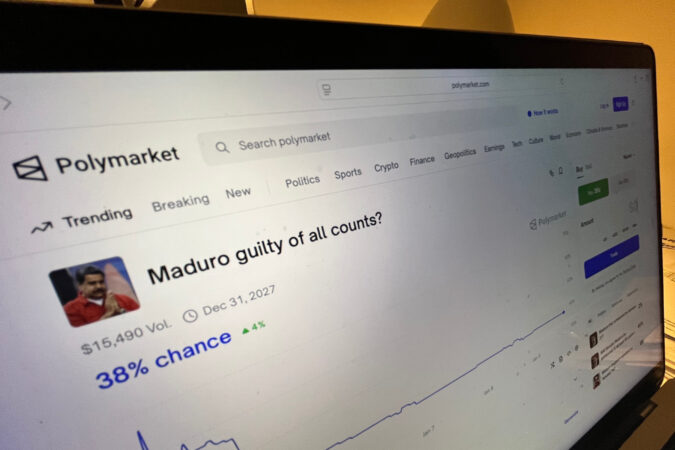

The chair of the federal Commodity Futures Trading Commission on Tuesday said the CFTC had filed a brief in federal court to “defend its exclusive jurisdiction” to oversee these markets, amid litigation between state governments and platforms such as Kalshi and Polymarket.

Prediction markets “provide useful functions for society by allowing everyday Americans to hedge commercial risks like increases in temperature and energy price spikes,” CFTC Chairman Mike Selig said in a video posted on X.

New Jersey collected more than $880 million in gaming tax revenues last year, while Pennsylvania brought in almost $3 billion, according to regulators. The revenues fund property tax relief programs and the horse racing industry, as well as programs for senior citizens and disabled residents.

Pennsylvania’s gaming regulator has previously warned that prediction markets risk “creating a backdoor to legalized sports betting,” without strict oversight.

The state Gaming Control Board’s Office of Chief Counsel told The Inquirer Wednesday that it sees a distinction between certain futures markets — like those for agricultural commodities, which have long been regulated by the CFTC — and “event contracts” tied to “the outcome of a random Wednesday night NBA basketball game.”

Representatives for Gov. Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania and Gov. Mikie Sherrill of New Jersey, both Democrats, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

But former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie — a Republican who worked to legalize sports betting while in office and who’s now advising the American Gaming Association — said Tuesday on X that the Trump administration is trying to “grow the size of the federal government & their own power while trying to crush states rights and take advantage of our citizens.”

Beyond the courts, the GOP-led Congress could also choose to step in. Some Republican lawmakers have expressed concerns about a “Wild West” in prediction markets, notwithstanding Trump’s support for the industry.

Sen. Dave McCormick (R., Pa.) welcomed the CFTC’s announcement, writing on X that prediction markets “offer tremendous benefits to consumers and businesses.”

“A consistent, uniform framework for derivatives is essential to supporting U.S. markets,” he said.

The CFTC’s action means the federal government is backing an industry in which the Trump family has a financial stake. The agency’s brief supports Crypto.com, a platform that last year partnered with the Trump family’s social media company to launch a prediction market.

Ethics experts have said the Trump family’s ties to Crypto.com create a conflict of interest. The White House denies that and says the president’s holdings are in a trust controlled by his children.

Winding through courts

The U.S. Supreme Court in 2018 struck down a federal law that prohibited sports betting in most states, paving the way for states to legalize it. Pennsylvania and New Jersey both enacted laws authorizing sports gambling and imposing requirements on betting operators such as taxation on gaming revenues, consumer protection rules, and licensing fees.

Despite state laws, prediction markets now operate nationwide — even in states that prohibit gambling altogether, like Utah.

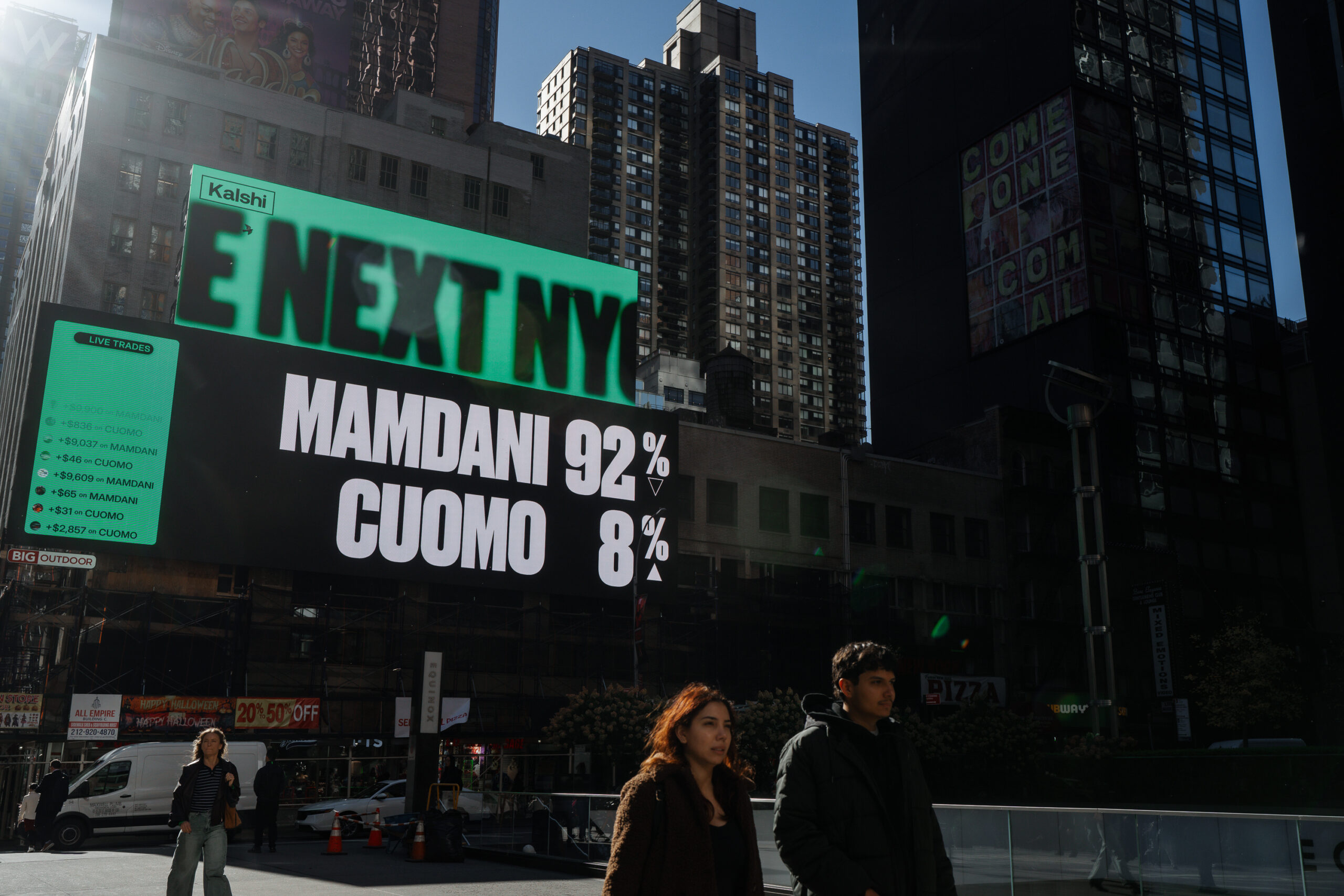

New York-based Kalshi launched its platform in 2021. The CFTC initially opposed Kalshi’s election-related contracts, but in the fall of 2024 the company won a case in which courts found the regulator failed to show how the platform’s “event contracts” would harm the public interest. Kalshi users proceeded to trade more than $500 million on the “Who will win the Presidential Election?” market.

Then came sports contracts. In January 2025, following the CFTC’s protocols, Kalshi “self-certified” that its contracts tied to the outcome of sports games complied with relevant laws.

The company has since offered event contracts on everything from the Super Bowl to Olympic Male Curling. Some established sportsbooks like Fanatics and DraftKings have also jumped into prediction markets.

About 90% of Kalshi’s trading volume is tied to sports, the Associated Press reported.

States have tried to intervene. In March, New Jersey’s gaming regulator ordered Kalshi to cease and desist operations in the Garden State, alleging the company issued unauthorized sports wagers in violation of the law and state Constitution.

Kalshi filed a lawsuit, and a federal court issued an injunction prohibiting New Jersey from pursuing enforcement actions. Kalshi and other platforms have filed suits against other states, and courts have issued conflicting rulings.

The CFTC said it filed a brief in one such suit this week.

“To those who seek to challenge our authority in this space, let me be clear: we’ll see you in court,” Selig, the Trump-appointed CFTC chairman, said Tuesday.

It could ultimately reach the U.S. Supreme Court.

‘Event contracts’

At issue is whether the “event contracts” offered by prediction markets amount to gambling — regulated by states — or, as Selig says, financial instruments “that allow two parties to speculate on future market conditions without owning the underlying asset.”

Platforms like Kalshi say they are similar to stock exchanges, where people on both sides of a trade can meet — and therefore subject to federal regulation of commodities. Unlike a casino, the platforms say, they don’t win when customers lose.

Pennsylvania regulators see it differently.

The state Gaming Control Board told The Inquirer Wednesday that it takes issue with “‘prediction markets’ allowing any consumer, age 18 years old or older, to purchase a ‘contract’ on any potential future event occurring, even when that event does not have any broad economic impact or consequence, such as the outcome of a random Wednesday night NBA basketball game.”

(Under Pennsylvania law, gambling is limited to those who are 21 or older.)

“The Board believes that is not what the Commodities Exchange Act contemplated when it was enacted by Congress and established the CFTC and is, in fact, gambling,” the board’s Office of Chief Counsel said in a statement.

If the courts side with the Trump administration, states worry that tax revenues from regulated sportsbooks would fall and customers would be vulnerable to markets they say are easily exploited by insiders.

“If prediction markets successfully carve themselves out of the ‘gaming’ definition, they risk creating a parallel wagering ecosystem where bets on sports outcomes occur with significantly less oversight regarding potential match-fixing,” Kevin F. O’Toole, executive director of the Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board, wrote in an October letter to the state’s congressional delegation.

For example, the gaming board has the ability to penalize licensed operators if they violate state regulations, O’Toole wrote, “something that an operator who ‘self-certifies’ their contracts/wagers [under CFTC rules] would never be subjected to.”

O’Toole said the board’s regulatory role in this area is limited to sports wagering, but he added that markets on non-sports related events — he cited examples from Polymarket such as whether there will be a civil war in the United States this year — are equally “if not more troubling.”

The CFTC says it is capable of overseeing the industry. “America is home to the most liquid and vibrant financial markets in the world because our regulators take seriously their obligation to police fraud and institute appropriate investor safeguards,” Selig wrote in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece this week.