Every day, sometimes several times a day, the 7-year-old girl wants to talk about the mother she lost in the Northeast Philadelphia plane crash.

“She’s missing her all the time and she’ll ask me, `Do you think I look like my mom? Do you think I dress like my mom? Do you see my bag? This is my mom’s bag,’” said 35-year-old Shantell Fletcher, the girl’s godmother.

It has been a year since a medical jet crashed on Cottman Avenue near the Roosevelt Mall, killing all six people onboard. The explosion cast a plume of plane shrapnel and fire over the neighborhood. At least 16 homes were severely damaged and about two dozen people were injured that night.

The girl’s mother, Dominique Goods Burke, and her fiance, Steven Dreuitt Jr., along with Dreuitt’s 10-year-old son, Ramesses Dreuitt Vazquez, were driving on Cottman Avenue on Jan. 31, 2025, just after 6 p.m. when the plane slammed into the ground at more than 278 mph, within feet of their car.

Flames instantly engulfed the vehicle. Dreuitt, 37, trapped in the car with his legs crushed beneath the steering wheel, died at the scene, but Goods Burke and Ramesses escaped with severe burns.

Goods Burke, 34, died of her injuries in April at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, leaving behind her daughter and her 16-year-old son, Dominick Goods. (The family asked The Inquirer to withhold her daughter’s name to protect her privacy.)

On Saturday evening, Mayor Cherelle L. Parker and other city officials planned to place a wreath at the crash site. About 100 people gathered inside Engine 71 Fire Station on Cottman, the station closest to the crash site.

The plane’s impact had left a bomb-like crater in a driveway apron between a Raising Cane’s restaurant and a Dunkin’ Donuts. The 8-foot-deep hole has since been filled in and paved over, but the loss and devastation are irreparable.

“I don’t know how we made it through a year. It feels fresh, raw. Sometimes it’s hard to breathe,” said Fletcher, who was Goods Burke’s first cousin and best friend. “Losing her, I’ve felt alone and empty. I miss laughing with her. I miss joking with her. I miss celebrating life with her.”

Fletcher is helping to raise Goods Burke’s daughter and her son, Dominick, an 11th grader at Imhotep Institute Charter High School in East Germantown. Dominick’s father was Dreuitt, so he lost both parents.

“My godson doesn’t have his mother or his father. My goddaughter doesn’t have her mamma,” Fletcher said. “Other than them coming back, nothing could ever give us a reprieve from the pain.”

Dominick’s half brother, Ramesses, suffered burns over 90% percent of his body. He spent about 10 months in the hospital, undergoing more than 40 surgeries. Doctors had to amputate his fingers and ears.

“I have my moments of still struggling. It’s been really tough,” said Dreuitt’s 61-year-old mother, Alberta “Amira” Brown, whose grandchildren are Ramesses and Dominick. “The life that we once had, we can never get it back.”

An irreplaceable booming voice

Dreuitt worked as a kitchen manager and team leader at the Philadelphia Catering Co. in South Philadelphia for more than seven years. Co-owner Tim Kelly said it was Dreuitt’s job to call staffers to lunch, which the company served to its 45 employees each day at noon.

“Steve would always call lunch, which basically was him just yelling, ‘LUNCH,’ three times loudly,” Kelly said. “His deep booming voice. Many of the guys here have tried to replicate it, but to no avail.”

“Time does help. It softens the blow,” Kelly said. “It was very difficult for a long time for a lot of us, but we’re at the point where we can remember him with a little less sadness and we can smile a bit.”

Goods Burke, whom loved ones affectionately called “Pooda” and colleagues called “Dom,” worked at High Point Cafe as a day bakery manager for years.

Cafe founder Meg Hagele said the staff treats her former work space, dubbed “Dom’s table,” with a shrine-like reverence. Seeing Goods Burke’s handwriting on recipes, scribbles in margins, stirs memories of her vibrancy and creativity.

“She’s very present with us still,” Hagele said. “This accident was just a shock to the entire city, but to be touched so personally by it is just freakish and profound.”

NTSB investigation continues

The National Transportation Safety Board is still investigating the crash’s cause. The plane — a medical transport Learjet 55 owned by Jet Rescue Air Ambulance, headquartered in Mexico City — had taken off at 6:07 p.m. from Northeast Philadelphia Airport. It climbed to 1,640 feet before nosediving just three miles away around 6:08 p.m.

NTSB investigators recovered the cockpit voice recorder at the scene, but after repairing it and playing it back, they found the device “had likely not been recording audio for several years,” according to a preliminary report released in March.

Brown, of Mount Airy, said she got a letter from the NTSB a few weeks ago saying investigators were making progress.

“That’s hope right there,” Brown said in a recent interview. ”It will help to know exactly what happened to make that plane come down. Does it change anything? No.”

The cremated remains of the six Mexican nationals who died aboard the plane were returned to loved ones in Mexico City last spring. Among the passengers were 11-year-old Valentina Guzmán Murillo and her 31-year-old mother, Lizeth Murillo Osuna. They were returning home after Valentina had spent four months undergoing treatment for a spinal condition at Shriners Children’s Philadelphia.

Also killed were the pilot, Alan Montoya Perales, 46; his copilot, Josue de Jesus Juarez Juarez, 43; a Jet Rescue doctor, Raul Meza Arredonda, 41; and paramedic Rodrigo Lopez Padilla, 41.

In the moments after the crash, hundreds of firefighters and rescue workers swarmed the area to put out homes and cars on fire from the jet fuel or burning pieces of aircraft that struck them.

Philadelphia Fire Commissioner Jeffrey Thompson, a 36-year veteran of the city’s fire department, said the plane crash “was without a doubt the biggest thing that I’ve ever responded to.”

In an interview on Thursday, Thompson recalled rushing to the scene from his Fishtown home, filled with dread and adrenaline.

“I remember it was dark. It was cold, and it was raining — it was like something out of a disaster movie,” Thompson said. “As I got closer, I could just see a sea of lights.”

He arrived to find multiple homes and cars on fire. Pools of jet fuel everywhere. And so many pieces of debris that he initially had no idea of the plane’s size. He said he and other first responders will never forget seeing body parts strewn among the wreckage.

“This still affects all of us. Just to see that is so unnatural,” Thompson said. “And the work that they did that night — that’s indelibly etched in their memories.”

More than 150 firefighters scoured “blocks and blocks” of homes, entering each one and every room, to make sure everyone was accounted for. He said he is amazed how multiple agencies worked together to bring “order to chaos.”

“That just gives me goose bumps,” Thompson said. He added, “This is actually therapeutic — me talking to you has been therapeutic because there was a lot there that night and I don’t often talk about this.”

Miracles, luck, and skill

As tragic as that night was, Thompson said, there was some miraculousness, including the fact that the plane struck a patch of empty pavement between two busy restaurants.

“Sometimes in this life, there’s luck,” Thompson said. “It was rush hour. You had a shopping mall and a densely populated neighborhood. It could have been infinitely worse.”

Andre Howard Jr. had just picked up his three kids — then ages 4,7, and 10 — from aftercare at Soans Christian Academy. They headed to Dunkin’ for strawberry doughnuts. As they were leaving the parking lot in Howard’s car, the plane exploded a few feet away. A plane part crashed through the car’s window. Howard’s 10-year-old son, Andre “Tre” Howard III, used his body to shield his 4-year-old sister and a piece of metal struck his head.

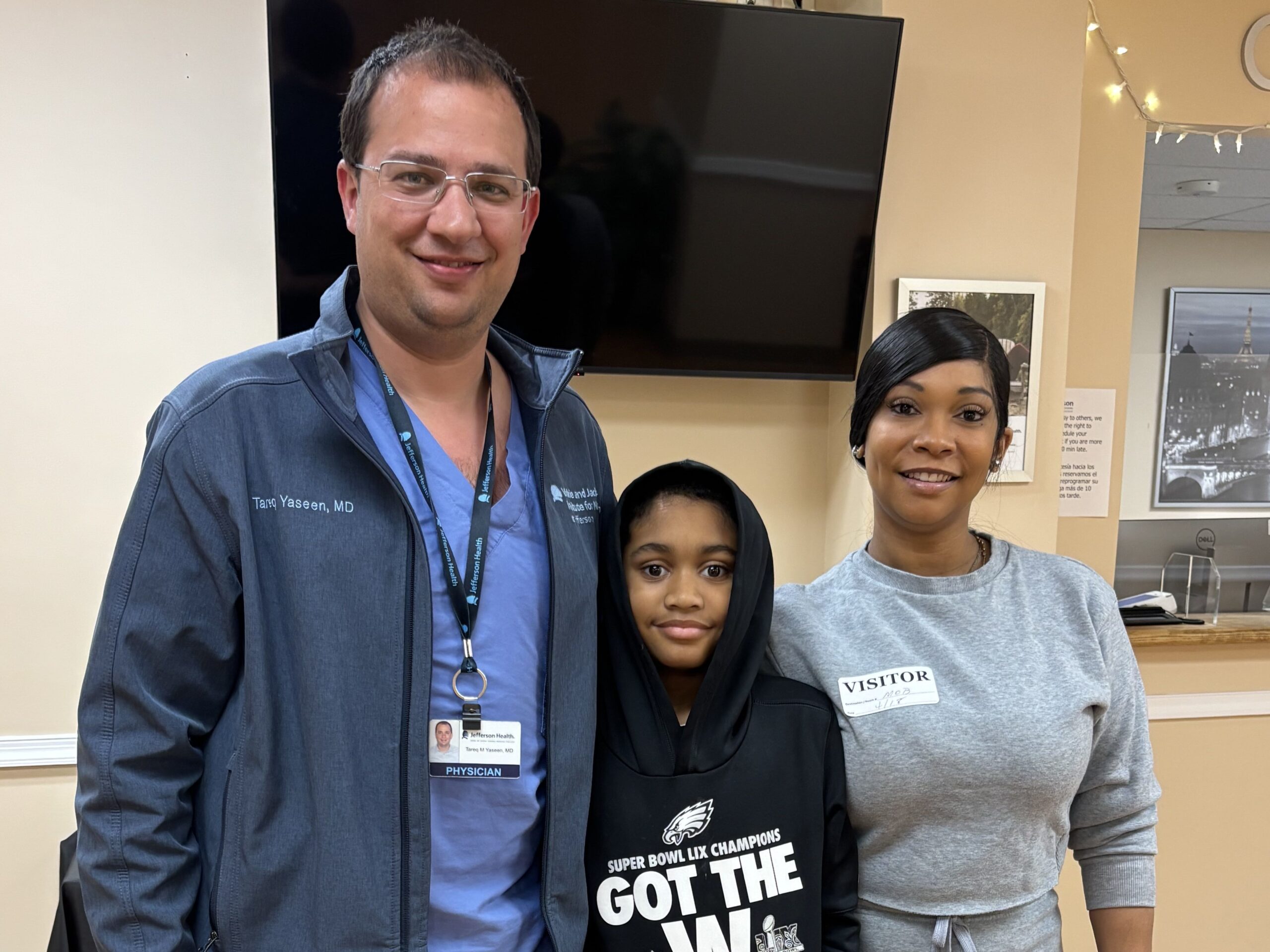

Tareq Yaseen, a neurosurgeon at Jefferson Torresdale Hospital, was having dinner with his family, including his kids, ages 10 and 6, at Dave & Buster’s at Franklin Mall when he rushed back to the hospital to perform emergency surgery on Tre.

The boy had two gashes in the right side of his head, and his skull had been shattered into more than 20 pieces, Yaseen recalled.

“My son is the exact age as Tre, which made things very personal and emotional to me,” Yaseen said. “He’s gonna die. He was basically losing consciousness and going in a bad direction.”

“I felt for a moment that I would not be able to help him,” Yaseen said. “I was very scared that I’m gonna fail. There’s too much on the line and it’s a little boy.”

Yaseen said he worked fast to relieve the pressure on Tre’s brain and remove bits of broken skull. The surgery was a success. More than 60 relatives and friends in the hospital waiting room hugged and thanked him, Yaseen recalled.

“It’s a moment that would happen in the movies,” Yaseen said. “I was very lucky to take part in saving his life.”

Tre was transferred to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, where he made a near-full recovery. He celebrated his 11th birthday in December.

“With time, he’ll grow up and forget about it. God gave us a gift to forget, which is great,” Yaseen said. “But I will never forget.”

A memorial

At the memorial Saturday, Mayor Parker read aloud the names of all eight who perished that night.

“To all the families who continue to carry this grief everyday, that until you’ve walked a mile in their shoes, you can’t begin to understand what it’s like,” Parker said. “It is important for us to affirm that they know that Philadelphia stands with you today and we will always.”

She asked the victims’ family members in attendance to stand and be recognized, including Brown, her grandson, Dominick, and Lisa Goods, the aunt of Goods Burke.

The mayor said she plans to keep close tabs on Dominick.

“Now he knows he belongs to me — don’t try to take him from me,” Parker said as she looked at Dominick seated in the front row.

Parker also recognized first responders for their “extraordinary bravery and selflessness.”

“In a moment of unimaginable tragedy, you all ran towards danger to protect others.”