Mayor Cherelle L. Parker’s administration last August told the U.S. Department of Justice that Philadelphia remains a “welcoming city” for immigrants and that it had no plans to change the policies the Trump administration has said make it a “sanctuary city,” according to a letter obtained by The Inquirer through an open-records request.

“To be clear, the City of Philadelphia is firmly committed to supporting our immigrant communities and remaining a welcoming city,” City Solicitor Renee Garcia wrote in the Aug. 25, 2025, letter. “At the same time, the City does not maintain any policies or practices that violate federal immigration laws or obstruct federal immigration enforcement.”

Garcia sent the letter last summer in response to a demand from U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi that Philadelphia end its so-called sanctuary city policies, which prohibit the city from assisting some federal immigration tactics. Bondi sent similar requests to other jurisdictions that President Donald Trump’s administration contends illegally obstruct immigration enforcement, threatening to withhold federal funds and potentially charge local officials with crimes.

Although some other cities quickly publicized their responses to Bondi, Parker’s administration fought to keep Garcia’s letter secret for months and initially denied a records request submitted by The Inquirer under Pennsylvania’s Right-To-Know Law.

The city released the letter this week after The Inquirer appealed to the Pennsylvania Office of Open Records, which ruled that the Parker administration’s grounds for withholding it were invalid.

The letter largely mirrors Parker’s public talking points about immigration policy, raising questions about why her administration sought to keep it confidential.

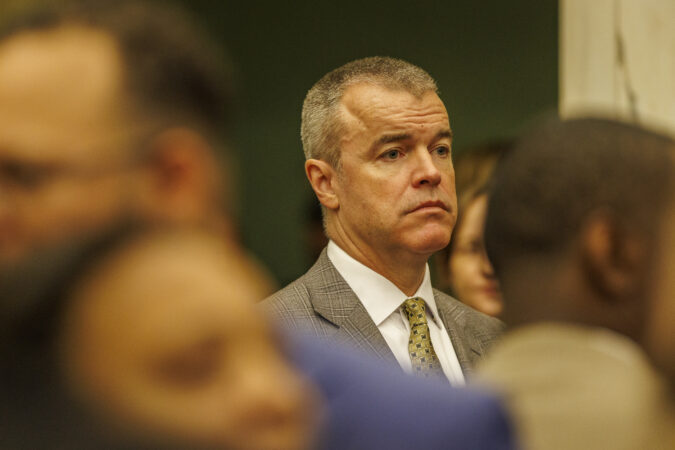

But the administration’s opaque handling of the letter keeps with the approach Parker has taken to immigration issues since Trump returned to office 13 months ago. Parker has vowed not to change immigrant-friendly policies enacted by past mayors, while avoiding confrontation with the federal government in a strategy aimed at keeping Philadelphia out of the president’s crosshairs as he pursues a nationwide deportation campaign.

Although U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers operate in the city, Philadelphia has not seen a surge in federal agents like the ones Trump sent to Minneapolis and other jurisdictions.

A spokesperson for the Justice Department did not respond to a request for comment.

Immigrant advocates have called on Parker to take a more aggressive stand against Trump, and City Council may soon force the conversation. Councilmembers Rue Landau and Kendra Brooks have proposed a package of bills aimed at further constricting ICE operations in the city, including a proposal to ban law enforcement officers from wearing masks. The bills will likely advance this spring.

Parker’s delicate handling of immigration issues stands in contrast to her aggressive response to the Trump administration’s removal last month of exhibits related to slavery at the President’s House Site on Independence Mall.

The city sued to have the panels restored almost immediately after they were taken down. After a federal judge sided with the Parker administration, National Park Service employees on Thursday restored the panels to the exhibit in a notable win for the mayor.

‘Sanctuary’ vs. ‘welcoming’

Bondi’s letter, which was addressed to Parker, demanded the city produce a plan to eliminate its “sanctuary” policies or face consequences, including the potential loss of federal funds.

“Individuals operating under the color of law, using their official position to obstruct federal immigration enforcement efforts and facilitating or inducing illegal immigration may be subject to criminal charges,” Bondi wrote in the letter, which is dated Aug. 13. “You are hereby notified that your jurisdiction has been identified as one that engages in sanctuary policies and practices that thwart federal immigration enforcement to the detriment of the interests of the United States. This ends now.”

“Sanctuary city” is not a legal term, but Philadelphia’s policies are in line with how the phrase is typically used to describe jurisdictions that decline to assist ICE.

Immigrant advocates have in recent years shifted to using the label “welcoming city,” in part because calling any place a “sanctuary” is misleading when ICE can still operate throughout the country. The newer term is also useful for local officials hoping to evade Trump’s wrath, as it allows them to avoid the politically hazardous “sanctuary city” label.

Philly’s most notable immigration policy is a 2016 executive order signed by then-Mayor Jim Kenney that prohibits city jails from honoring ICE detainer requests, in which ICE agents ask local prisons to extend inmates’ time behind bars to facilitate their transfer into federal custody. The city also prohibits its police officers from inquiring about immigration status when it is not necessary to enforce local law.

Garcia wrote in the August letter that Kenney’s order “was not designed to obstruct federal immigration laws, but rather to clarify the respective roles of the Police Department and the Department of Prisons in their interactions with the Department of Homeland Security when immigrants are in City custody.” The city, she wrote, honors ICE requests when they are accompanied by judicial warrants.

Immigration enforcement is a federal responsibility, and — in a case centered on Kenney’s order — the Philadelphia-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ruled in 2019 that cities do not have to assist ICE.

The court, Garcia wrote, “held that the federal government could not coerce Philadelphia into performing immigration tasks under threat of federal repercussions, including the loss of federal funds.”

City loses fight over records

In Pennsylvania, all government records are considered public unless they are specifically exempted from disclosure under the Right-To-Know Law. In justifying its attempt to prevent the city’s response to the Trump administration from becoming public, the Parker administration cited two exemptions that had little to do with the circumstances surrounding Garcia’s letter.

First, the administration argued that the letter was protected by the work product doctrine, which prevents attorneys’ legal work and conclusions from being shared with opposing parties. Given that the letter had already been sent to the federal government — the city’s opponent in any potential litigation — the doctrine “has been effectively waived,” Magdalene C. Zeppos-Brown, deputy chief counsel in the Pennsylvania Office of Open Records, wrote in her decision in favor of The Inquirer.

“Despite the [city’s] argument, the Bondi Letter clearly establishes that the Department of Justice is a potential adversary in anticipated litigation,” Zeppos-Brown wrote.

Second, the city argued that the records were exempted from disclosure under the Right-To-Know Law because they were related to a noncriminal investigation. The law, however, prevents disclosure of records related to Pennsylvania government agencies’ own investigations — not of records related to a federal investigation that happen to be in the possession of a local agency.

“Notably, the [city] acknowledges that the investigation at issue was conducted by the DOJ, a federal agency, rather than the [city] itself,” Zeppos-Brown wrote. “Since the DOJ is a federal agency, the noncriminal investigation exemption would not apply.”

Garcia’s office declined to appeal the decision, which would have required the city to file a petition in Common Pleas Court.

“As we stated, the City of Philadelphia is firmly committed to supporting our immigrant communities as a Welcoming City,” Garcia said in a statement Wednesday after the court instructed the city to release the letter. “At the same time, we have a long-standing collaborative relationship with federal, state, and local partners to protect the health and safety of Philadelphia, and we remain [in] compliance with federal immigration laws.”

Staff writers Anna Orso and Jeff Gammage contributed to this article.