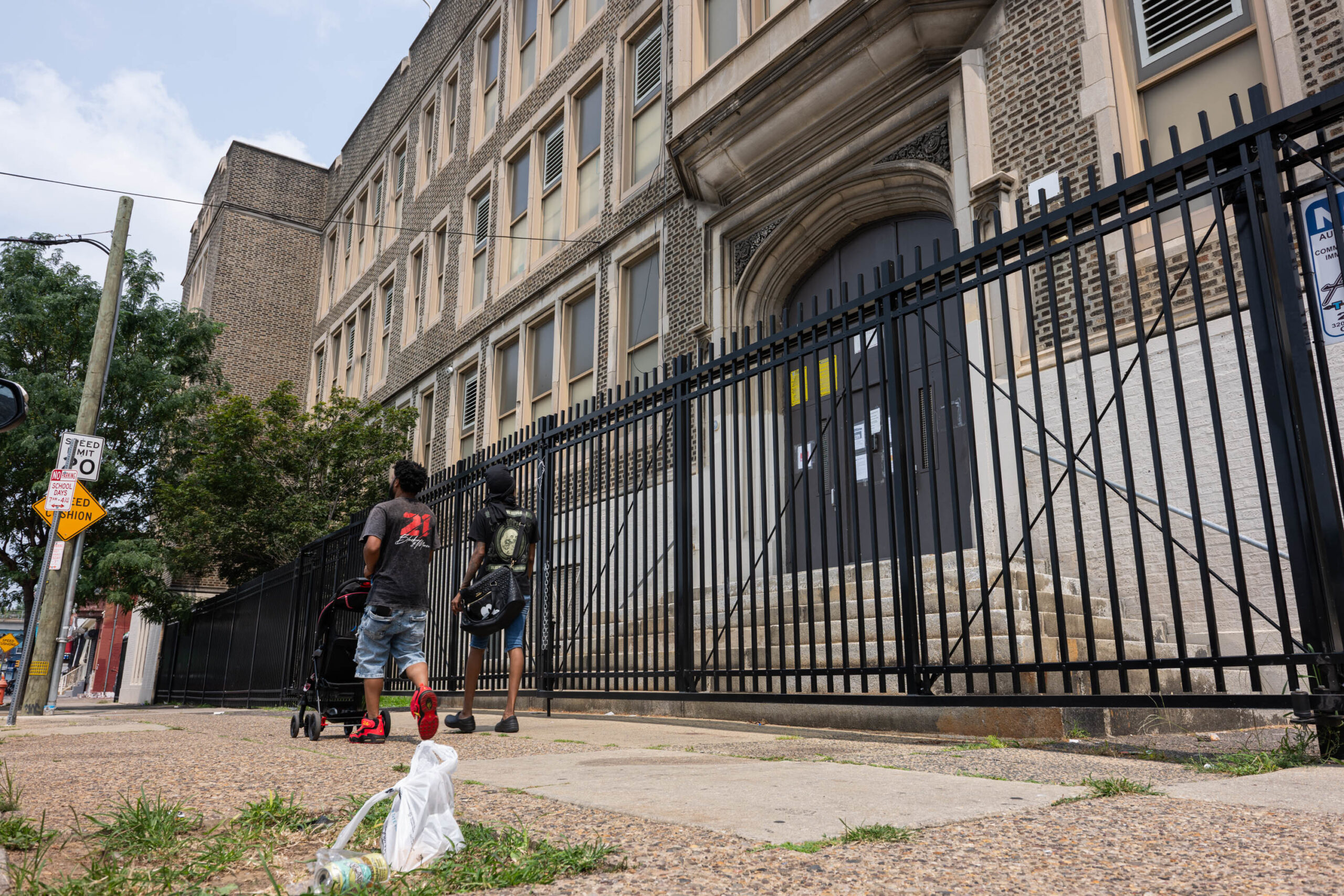

Russell H. Conwell Middle School celebrates its 100th anniversary this year.

It may not remain open to see many more.

The Philadelphia School District has proposed closing Conwell and 19 other schools as part of its facilities planning process, which will shake up schools citywide.

Conwell, in Kensington, is a very small school by any standard. This year, just 109 students are enrolled in a building that holds 500. That’s down from 490 students in the 2015-16 school year and 806 in 2009-10. The school used to occupy two buildings; it has since shrunk to one.

But it is also a rarity — a standalone magnet middle school. Community members and local officials are mounting a fight against closing the school, which they say has committed teachers and staff members who help students excel against the odds.

The district’s plan, which the school board is expected to vote on this winter, calls for Conwell students to move to AMY at James Martin, another citywide admissions magnet in Port Richmond, which just opened in a new building with only 200 students. Meanwhile, the district has proposed closing its only other free-standing magnet middle school, AMY Northwest. No changes have been proposed for Philadelphia’s four other magnet middle schools, all of which are attached to high schools.

Neighborhood issues, enrollment declines

Conwell’s enrollment issues are tied closely to its setting.

The building sits on Clearfield Street in the heart of Kensington. Fewer and fewer parents have been choosing to send their kids into ground zero of the city’s opioid epidemic, despite Conwell’s myriad partnerships, the outside investments it has attracted into its facility in recent years, and the school’s long history of excellence.

Parents, neighbors, students, and politicians, however, are furious that the district is choosing to abandon Conwell and the neighborhood.

“If this school closes, it won’t just be students who feel the loss,” Conwell student Nicolas Zeno told officials at a district meeting Thursday. “It’ll be the community. If the concern is safety, then invest. If the concern is environment, then repair.”

Community member Vaughn Tinsley, who runs Founding Fatherz, a nonprofit mentoring group, suggested closing Conwell would harm its students.

“These students have been victims,” Tinsley said. “These students have seen and witnessed things they shouldn’t have witnessed. Most adults haven’t seen some of the things that these kids have seen, and yet still they come here, yet they’re still committed to excellence, yet they still stand up and still do what they’re supposed to do in the classroom. How dare we take that away from them?”

Watlington has proposed using Conwell as “swing space” — district property that other schools can move into temporarily if their buildings require repairs.

Tosin Efunnuga, Conwell’s nurse, wiped tears from her eyes as she beseeched district officials to keep the school open.

“To have those doors close would be such a disservice,” Efunnuga said. “We need 100 years more.”

Councilmember Quetcy Lozada, whose district includes Conwell, said she was “angry” and “frustrated” by the recommendation to close the school.

“It’s underutilized because of what’s happening on the outside,” Lozada said at the Conwell meeting. “There’s nothing wrong with what is happening on the inside other than successful academic learning, support for families. We are saying to these families, we are punishing them because as a city, we can’t respond to the public safety issues that we have on the outside, and that is just not fair.”

‘What are y’all doing?’

Emotions ran high inside the Conwell auditorium last week.

Even before Deputy Superintendent Oz Hill finished his presentation about the rationale for the closures and the specific plan for Conwell, parents burst out with concerns.

“What are y’all doing? Y’all making a mess,” one parent shouted. “You say the building is old. So what? It’s clean in here.”

Another said her child would not be going to AMY at James Martin, formerly known as AMY5.

“I don’t think you understand how much of a battle there is between Conwell and AMY5,” the parent said. “You don’t know the battles these kids have with each other.”

Conwell has a strong alumni network — a rarity for a middle school — that has turned out in force to support the school since the proposed closure was announced.

Alexa Sanchez, Class of 2017, grew up in Kensington and came to Conwell as a bright but unruly student — she acknowledges that she got in fights, egged the school, and disrespected teachers. But Conwell is rooted in its neighborhood, Sanchez said, with dedicated staff who helped her rise to earn a college degree and a good job in business.

“They didn’t give up on students like me,” Sanchez said. “My future didn’t look promising at first, but in the long run, it did. You shouldn’t really close the school on a community that doesn’t look promising if you’re not from here.”

Other alumni, including Robin Cooper, president of the district’s principals union, and Councilmember Isaiah Thomas, chair of Council’s Education Committee, have spoken out for Conwell.

Conwell “shows up” for Kensington and the city, running a food pantry, hosting Police Commissioner Kevin Bethel’s swearing-in ceremony and an event marking Cherelle L. Parker’s 100th day as mayor, noted Erica Green, the school’s award-winning principal. Staff and students participate in neighborhood cleanups and advocate for help amid the opioid crisis.

“We are what the city needs,” Green told the school board recently. During Green’s tenure, she has helped win money for a new schoolyard, a new science, technology, engineering, and math lab, and more.

“These investments were made for Kensington students,” Green said. “We owe it to them, to their neighborhood. Do not push them out once the neighborhood changes and thrives. Conwell’s success is rooted in its people, its history, and its impact.”