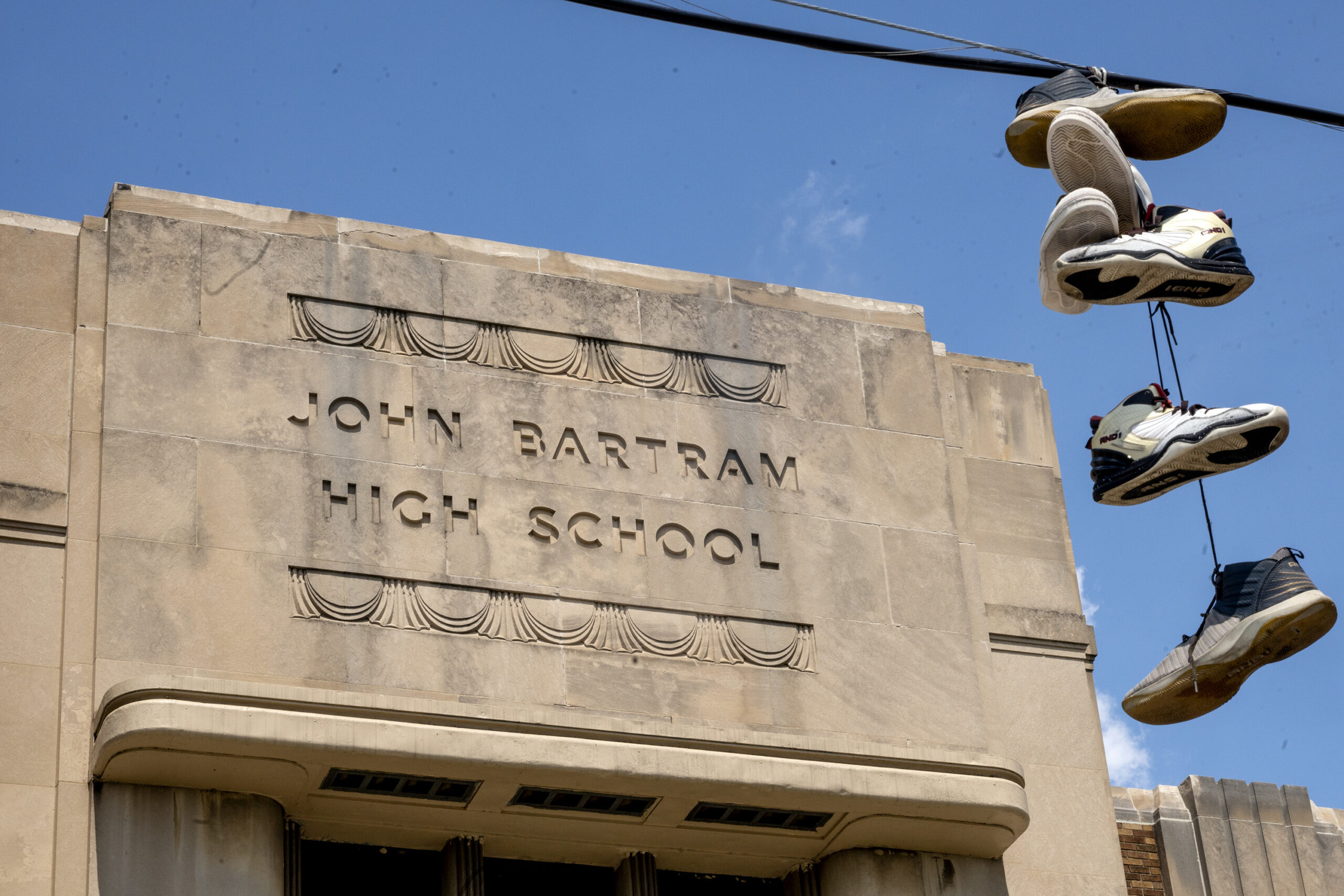

Nearly $58 million for South Philadelphia High School. Over $27 million for Forrest Elementary in the Northeast. Almost $55 million for Bartram High in Southwest Philadelphia.

Ahead of a Tuesday City Council hearing on the Philadelphia School District’s proposed facilities master plan, district officials have dangled the carrot that would accompany the stick of 20 school closings.

The district released Monday morning how much it would spend on modernization projects at schools in each City Council District if Superintendent Tony B. Watlington Sr.’s plan is approved by the school board this winter.

The totals range from $443 million in the 9th District — which includes parts of Olney, East and West Oak Lane, Mount Airy, and Oxford Circle — to nearly $56 million for the 6th District in lower Northeast Philadelphia, including Mayfair, Bridesburg, and Wissinoming.

The district’s announcement comes as the plan has already raised hackles among some Council members, and City Council President Kenyatta Johnson has said he’ll hold up the district’s funding “if need be” if concerns are not answered to Council’s satisfaction.

Tailoring the release to Council districts — including highlighting one major project per district — appears to be an effort to calm opposition ahead of Tuesday’s hearing.

Details on every school that would get upgraded under Watlington’s plan — 159 in total — have not yet been released.

Watlington has stressed that the point of the long-range facilities plan is not closing schools, but solving for issues of equity, improving academic programming, and acknowledging that many buildings are in poor shape, while some are underenrolled and some are overenrolled.

“This plan is about ensuring that more students in every neighborhood have access to the high-quality academics, programs, and facilities they deserve,” Watlington said in a statement. “While some of these decisions are difficult, they are grounded in deep community engagement and a shared commitment to improving outcomes for all public school children in every ZIP code of Philadelphia.”

But at community meetings unfolding at schools across the city that are slated for closure, Council members have expressed displeasure about parts of the plan — a preview, perhaps, of Tuesday’s meeting.

Councilmember Quetcy Lozada, represents the 7th District, including Kensington, Feltonville, Juniata Park, and Frankford. Four schools in her district — Stetson, Conwell, Harding, and Welsh — are on the chopping block.

“The fact that they are being considered for closure is very concerning to me,” Lozada said at a meeting at Stetson Middle School on Thursday.

Councilmember Cindy Bass, speaking at a Lankenau High meeting, objected to closing schools that are working well. (Three schools in Bass’ 8th District, Fitler Elementary, Wagner middle school, and Parkway Northwest High School, are proposed for closure. Lankenau is in Curtis Jones Jr.’s district but has citywide enrollment.)

“I do not understand what the logic and the rationale is that we are making these kinds of decisions,” said Bass.

While Council members will not have a direct say on the proposed school closures or the facilities plan, Council wields significant control over the district’s budget. Funding for the district is included in the annual city budget that Council must approve by the end of June.

Local revenue and city funding made up about 40% of the district’s budget this year, or nearly $2 billion. Most of that is the district’s share of city property taxes which, unlike other school systems in Pennsylvania, are levied by the city and then distributed to the district.

(function() {

var l2 = function() {

new pym.Parent(‘schools_districts2’,

‘https://media.inquirer.com/storage/inquirer/projects/innovation/arcgis_iframe/schools_districts2.html’);

};

if (typeof(pym) === ‘undefined’) {

var h = document.getElementsByTagName(‘head’)[0],

s = document.createElement(‘script’);

s.type = ‘text/javascript’;

s.src = ‘https://pym.nprapps.org/pym.v1.min.js’;

s.onload = l2;

h.appendChild(s);

} else {

l2();

}

})();

Where will the money go?

Despite city and schools officials saying in the past that the district has more than $7 billion in unmet facilities needs, Watlington has said the district could complete its plan — including modernizing 159 schools — for $2.8 billion.

Officials said further details about modernization projects and the facilities plan will be released before the Feb. 26 school board meeting, where Watlington is expected to formally present his proposal to the school board.

Here are the total proposed dollar amounts per Council district and the 10 big projects announced Monday:

- 1st District: $308,049,008. Key project: $57.2 million for South Philadelphia High, turning the school into a career and technical education hub and modernizing electrical, lighting, and security systems.

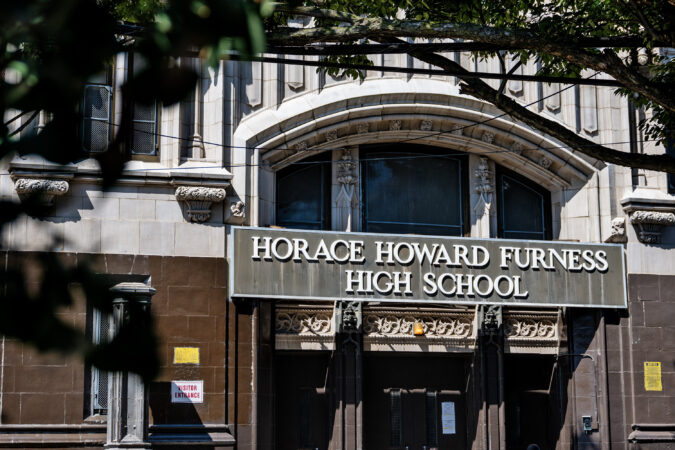

- 2nd District: $302,284,081. Key project: $54.6 million for Bartram High, to renovate the school and grounds, career and technical education spaces, restroom and accessibility renovations, new painting, and new athletic fields and facilities (on the site of nearby Tilden Middle School, which is slated to close). Motivation High School would close and become an honors program inside Bartram.

- 3rd District: $204,947,677. Key project: $19.6 million for the Sulzberger site, which currently houses Middle Years Alternative and is proposed to house Martha Washington Elementary. (It currently houses MYA and Parkway West, which would close.) Improvements would include heating and cooling and electrical systems, classroom modernizations, and the addition of an elevator and a playground.

- 4th District: $216,819,480. Key project: $50.2 million for Overbrook High School, with updates including new restrooms, accessibility improvements, and refurbished automotive bays. (The Workshop School, another district high school, is colocating inside the building.)

- 5th District: $290,748,937. Key project: $8.4 million for Franklin Learning Center, with updates including for exterior, auditorium, and restroom renovations, security cameras, accessibility improvements, and new paint.

- 6th District: $55,769,008. Key project: $27.2 million for Forrest Elementary, including modernizations that will allow the school to grow to a K-8, and eliminate overcrowding at Northeast Community Propel Academy.

- 7th District: $388,795,327. Key project: $32.3 million at John Marshall Elementary in Frankford to add capacity at the school, plus a gym, elevator, and schoolwide renovations.

- 8th District: $318,986,215. Key project: $42.9 million at Martin Luther King High in East Germantown for electrical and general building upgrades and accommodations for Building 21, a school that will colocate inside the King building.

- 9th District: $442,934,244. Key project: $42.2 million at Carnell Elementary for projects including an addition to expand the school’s capacity, restroom renovations, exterior improvements, and stormwater management projects.

- 10th District: $275,829,539. Key project: at Watson Comly Elementary in the Northeast, an addition to accommodate middle grade students from Loesche and Comly, and building modernizations. District officials did not give the estimated cost of the Comly project.

What’s next?

The facilities Council hearing is scheduled for 10 a.m. Tuesday at City Hall. It will also be livestreamed.

Members of the public also have the opportunity to weigh in on the facilities plan writ large at three community town halls scheduled for this week: Tuesday at Benjamin Franklin High from 4:30 to 6:30 p.m., Friday at Kensington CAPA from 4:30 to 6:30 p.m., and a virtual meeting scheduled for 2 p.m. on Sunday.

Meetings at each of the schools proposed for closure continue this week, also; the full schedule can be found on the district’s website.