New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy’s digital innovation office has been made a permanent cabinet-level office in what appears to be the first move of its kind in the nation as the role of artificial intelligence increases in government.

Murphy created the New Jersey State Office of Innovation in 2018 to improve digital innovation in state government.

And now it’ll remain a fixture in New Jersey after he leaves office, following Murphy’s signing Monday of a bill that turns the office into an authority within the Treasury Department.

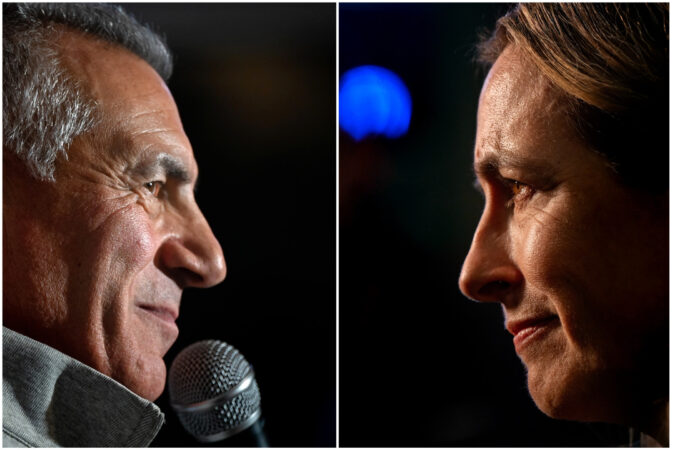

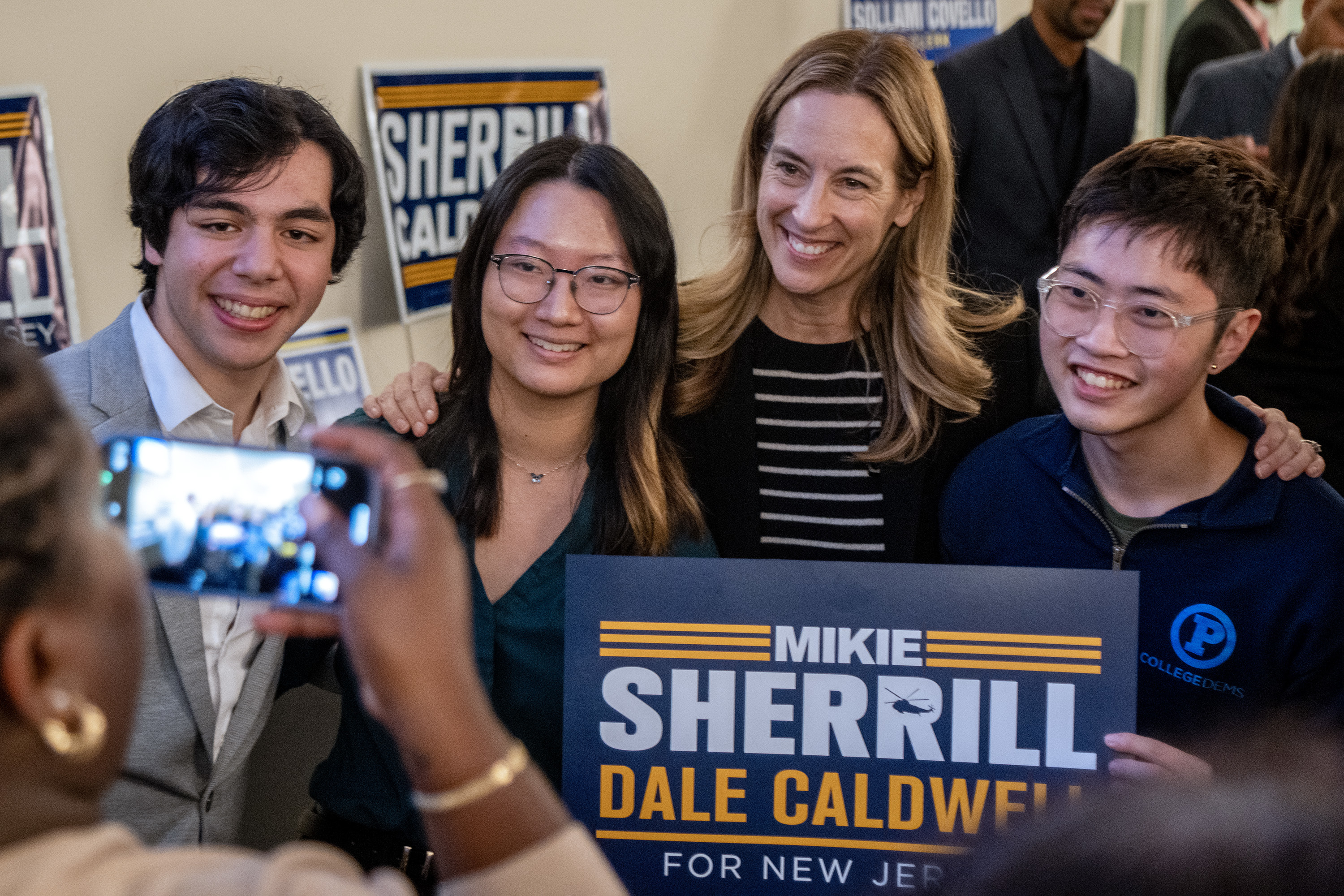

Gov.-elect Mikie Sherrill, who will be inaugurated on Jan. 20, will oversee the new authority. Sherrill supports the office, but even if she didn’t, the new law means a governor can’t just get rid of it.

Georgetown University’s Beeck Center, which tracks these efforts nationally, has identified 17 states with digital innovation offices, including Pennsylvania. But the university and Murphy’s office say New Jersey is the first to codify a cabinet-level position of its kind into law.

The new law also helps the office fund projects between departments more easily and opens up the possibility of revenue streams such as by selling its technology to other state governments or local governments within the state, said Dave Cole, a Haddonfield resident who leads the department. The law also requires a board of directors appointed by the governor.

The state innovation office has worked with almost every state agency to identify problems that can be fixed with technology in an effort to make government services more efficient, Cole said.

In one example, it helped the Department of Labor redesign emails for its unemployment program, which had used decades-old design technology and hard-to-understand legalese that was slowing down the claim process because it wasn’t user-friendly.

In another, the office used machine learning to identify 100,000 students eligible for summer food assistance who weren’t getting it.

The office has also modernized call centers and even created an internal AI chat bot for state employees that helps draft emails, summarize documents, and analyze public feedback — shaving days off the process of aggregating public comments.

Employees are told repeatedly that AI is a tool and that human review is still needed, Cole said.

“The person that’s using the AI needs to be accepting responsibility for the use of and any dissemination of information after they’ve reviewed it,” he said in an interview.

The office was awarded what it called a “first of its kind” grant last month to utilize AI in government.

Cole, 40, said his team’s approach to AI is to make bureaucratic processes more efficient, like summarizing fraud information, generating memos, and matching disparate data sets.

“Our purpose isn’t to solve an AI problem as much as it is to solve a resident problem, a business owner problem — sometimes, when we work with higher education, an institutional problem,” he said. “And often AI, more recently, emerges as a tool that can help us through that.”

The bill passed by 29-8 in the Senate with three members not voting on Dec. 22 and by 61-13 in the Assembly on Dec. 8, with four members not voting and two abstentions.

Sherrill said she will keep Cole in his position as she puts together her administration.

“I look forward to working with Dave as we modernize the way New Jerseyans access state government services and build a government that works for everyone,” Sherrill said in a statement.

Cole, a Rutgers grad, worked with data and analytics as an organizer for former President Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign before developing the White House website and online petitions as part of the presidential administration.

That work was simpler than the projects he does now given the rapid development of AI — but reached the same goal of increased civic engagement, he said.

After his work there, Cole then pivoted to the private tech sector and made an unsuccessful bid for Congress in South Jersey in 2016 before joining the state’s innovation office in 2020 to help with pandemic vaccine distribution before eventually rising to chief innovation officer a year ago, replacing Beth Noveck, who now works as the chief AI strategist in the same office.

“Generally speaking, there’s a lot of pain. There’s a lot of unsolved problems. There’s a lot of improvements that we need to see,” Cole said. “And so if we understand how to effectively leverage technology, we can do good there, but we have to be careful with anything like this.”

One project Cole is looking forward to this year is building the option for residents to use one online account for various government agencies and allowing for their data to be shared across departments to pre-populate forms.

Not only can that simplify processes for residents who choose to participate, but it can make it easier for government agencies to recommend different government programs by getting information about applicants it wouldn’t otherwise receive, he said.

“Having that information allows us to do really interesting things, like ‘You’re enrolled in this program, did you know you may also be eligible for this other program?’” he said. “This has been for a long time, I think, sort of a dream of folks who do this kind of digital technology work to recommend and automatically enroll people in benefits based on their eligibility.”

Working with Sherrill to cut through red tape

Sherrill campaigned on “cutting through that red tape and bureaucracy.” When asked to elaborate by The Inquirer at a mid-November campaign appearance in South Jersey, she said “a lot of it is just putting stuff online.”

She also said she wants to address redundancies for residents who need to go through different government organizations and find out they have more steps than they initially thought.

“I’ve heard too many stories of people who do the five steps they need to get a permit, and they go back and they go, ‘Well, here’s five more,’” she said in November. “So there’s not a lot of clarity, transparency, or accountability in getting through this process.”

That’s the kind of work the innovation office has been doing through business.nj.gov, a centralized website for starting and growing a business, and Cole looks forward to doing more of it in partnership with Sherrill.

New businesses that use the website launched an average of a couple of weeks sooner than those that didn’t, Cole said.

“It has many agencies, permits, and licenses integrated in it, but not all,” he said.

“And one of the challenges is that agencies have many priorities about the things that they need to work on at a given point in time, so I think the governor-elect’s focus on this could allow more clarity there,” he added.

This article has been updated to reflect the office is cabinet-level.