The legacy of Catholic Charities of Philadelphia originated in 1797 with the Catholic Church’s establishment of an orphanage during the yellow fever epidemic. This initial act of charity laid the foundation for a tradition of service that has persisted. Today, the nonprofit is an umbrella organization that offers a wide range of essential services to more than 300,000 people throughout the five-county region. “We’ve been here a long time,” Heather Huot, Catholic Charities’ secretary and executive vice president, said. “Over 200 years, but I don’t know that we’ve always done a really good job of talking about the good work that we do.” Its current mission includes providing family and senior services, foster care, adoption, and support for the homeless. Below, Huot discusses the charity’s values and what keeps her hopeful.

How would you describe what Catholic Charities does and why it matters in Philadelphia?

We provide food, housing, care for seniors, families, and individuals, and everything that we do is driven by faith in Jesus and rooted in the works of mercy to serve our neighbors with love and dignity. We really put the mission of the archdiocese into action every day. We provide vital support across not just Philadelphia County, but the surrounding counties as well.

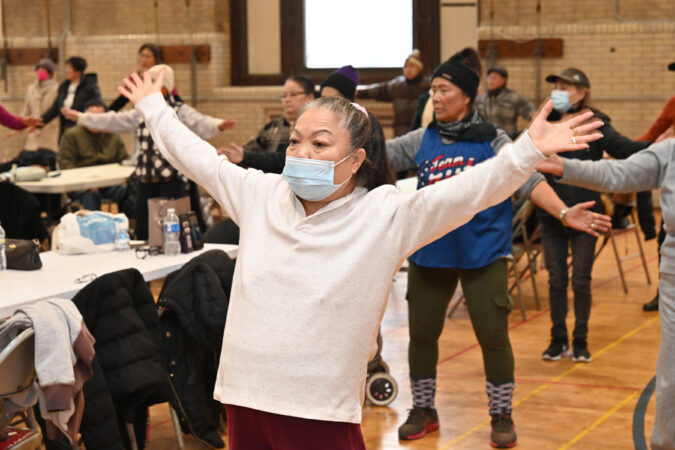

We divide our work into four pillars. We nourish the hungry and shelter the homeless. Just this past week, we had about 1,500 individuals experiencing homelessness come right through our parking lot here by the cathedral to get essentials for winter. And we also provide shelter and we stock pantries all across the region.

The second thing that we do is we strengthen and support at-risk children and youth. We’re talking from the time they’re toddlers all the way up through young adulthood, really trying to touch people throughout that whole spectrum of their life. [We do] some residential care, some work with DHS [Department of Human Services], [and we’re] trying to teach trades and skills. [For our third pillar], we stabilize and enrich the lives of seniors in our communities. It’s really important to think about seniors who’ve given so much to our communities.

Then the fourth pillar of our service is empowering individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. We provide residential care to about 400 individuals every day that are living with intellectual and developmental disabilities. So it’s a wide range of services across the five-county region.

What led you to social work and how did that path bring you to Catholic Charities?

It’s actually a little bit of a roundabout journey. I grew up with a sibling with special needs, so I always thought I was going to be a special education teacher. But in my senior year of college I did student teaching where you spend a full semester in the classroom, and I hated it. So I decided, since I wasn’t quite sure what my next step would be, rather than getting a job or going to grad school, I would take a year and dedicate it to service.

I just happened to be placed at St. Francis Inn, a soup kitchen here in Kensington, and I spent a year living and working at the soup kitchen, where I just fell in love with working with folks who were coming in every day. At St. Francis, they really take on this notion of radical solidarity with the folks who are coming for food and compassion. And I was so moved by it. I knew I had to stay in that world. I decided to move into social services and I was very blessed to find my way to Catholic Charities at that point in my life. That was 26 years ago.

The organization serves more than 300,000 people annually through more than 40 programs. What connects all of these programs together?

It is really interesting because we are 40 programs but also over a hundred different [service] locations. Every program that we have, no matter where it is in the five-county region, we’re living out that call to care for our neighbors. It’s driven by love.

Our mission is person-centered, focused on wanting the best for every person we encounter. And you’re going to find that no matter what kind of program you step into, that’s the heart of what we do. It may be handing out meals, it may be caring for someone who’s aging, but that’s the foundation.

I think the second thing that kind of unites all of our programs together is we’re also a place where the community can engage in works of charity and service. So it’s not just about our staff and my colleagues doing this work; we are a place for people to join us in that work.

How does your clinical training in social work inform the way you approach leadership at Catholic Charities?

Social work is a very humbling position; it’s not a position that you go into thinking you have all the answers for everyone’s problems. It’s really about meeting people where they are and walking alongside them. It’s about attentive listening and knowing that you are not the smartest person who’s going to wave the magic wand and make things better.

And I think I’ve really brought that into my role now as executive vice president. We need to be a collective in how we solve problems. We need to ask, how do we bring in people that believe in our mission to help us solve this problem? Because we don’t necessarily have all the resources that the community’s going to need; we’ve got to be creative and find those who want to partner with us.

How does Catholic Charities approach long-term issues like housing? How do you build that into programs?

At the St. Francis Inn, we would see the same people every day and their lives weren’t changing. I loved [doing the work], but I also felt very frustrated. I would always ask myself the question, “Well, how’s this going to get better for them?” So I’ve come to learn that a social service agency like ours can have programs that are meeting immediate needs, but we also need to balance that with programs that provide more long-term systemic change, like creating affordable housing. We train youth on carpentry skills, giving them a real trade so that they can go into the world in a different way than maybe their parents did.

[And] I think when you think about stability, it’s really only possible when you have a reliable base of support and trusting relationships. So if we’re giving out food at Martha’s Choice Marketplace, it’s me also learning your name and why you are coming for food, and [asking if] there’s anything else that we can help you with or if there is anyone else I connect you with.

We build affordable housing. That’s huge. It’s a solution in and of itself. However, there’s more to it than that, right? It’s about engaging with the residents once they’re there so they can actually maintain that stability. I was visiting Guiding Star Ministries, one of our ministries that supports expectant mothers. It’s a residence where they can live as they’re preparing for the birth of their child and then they can stay with us for up to a year once their child is born. So for someone who maybe does not have the best living situation, who becomes pregnant, it gives them a safe place to prepare and then have their child.

I asked the staff, what’s the key to a mom doing well once they leave? And they said, [it’s] always [having] someone to call when something goes wrong later.

I think the other part that’s really important for me in my role is that I have to focus on advocacy, too. I meet with city, state, and federal leaders to talk about what our communities need. I invite them to come and see what we’re doing to engage in our work, because that’s how they’re going to understand the impact of the dollars that they’re allocating.

This is a tough legislative environment. What gives you hope day to day as you try to gather resources to serve the community?

Right now that hope may be hard to see. I mean, you just see so much sadness around us, but I’ll tell you what: my colleagues [make me hopeful]. Our staff is very diverse. I know we are Catholic Charities, but that doesn’t mean that everyone we serve is Catholic. That is far from the truth. And it does not mean all of our staff is Catholic. But we are united by this mission to care for our most vulnerable sisters and brothers. And you see that in action every day with them. And that’s what keeps me coming to work every day and feeling like we can do this.

What would you like your legacy to be when people look back at your time at Catholic Charities?

My five-year plan is to bring a lot of our different services together, talking to each other, being more collaborative. You’re really going to see that be the focus over the next five years.

But, [longterm,] I want people to look back at my time in this role and think that it was a time of growth. I know there’s a lot of other things going on in the world around us, but I think this is the time for Catholic Charities to be on the front lines and show that we are such a force for good in the Philadelphia region. And that I bring a spirit of collaboration and hope to my organization.

I think one of the things that’s really important to note is it’s also an important time for the Catholic Church of Philadelphia. The archbishop is taking very bold steps to bring people back to the Catholic Church. He has a strategic plan that’s out there, and I think that we, as Catholic Charities, can be the frontline for welcoming people back. People might not be comfortable walking into church, but they might be comfortable coming and serving a meal with us. And I think that’s a really important role for us to play.

PHILLY QUICK ROUND

What’s your favorite Philly food splurge? Sweet Lucy’s Smokehouse. It is a little barbecue joint in Northeast Philly. I love the pulled pork and the cornbread.

Favorite Philly small business? Mueller Chocolate Company in Reading Terminal Market. Their chocolate-covered pretzels are my favorite. I have quite the sweet tooth.

You don’t know Philly until you’ve… taken your family to a Flyers game to kick off your Christmas celebrations. There’s Gritty Santa Claus!

Who’s the greatest Philadelphian of all time? Saint Katharine Drexel, [both] as a Philadelphian and as a woman Catholic leader. I can’t think of a better role model for myself. She took care of people that were pushed aside and oppressed, and she was a tireless advocate for their dignity.

What do you do for fun around Philly? Well, I do love theater and the performing arts, so I’m always looking to take in a show, whether that be at the Academy of Music or the Arden.

What’s one place in or around Philadelphia you wish everyone would visit at least once? Boathouse Row, especially during a regatta. There is just something really special about the Schuylkill River and seeing rowing in action there.