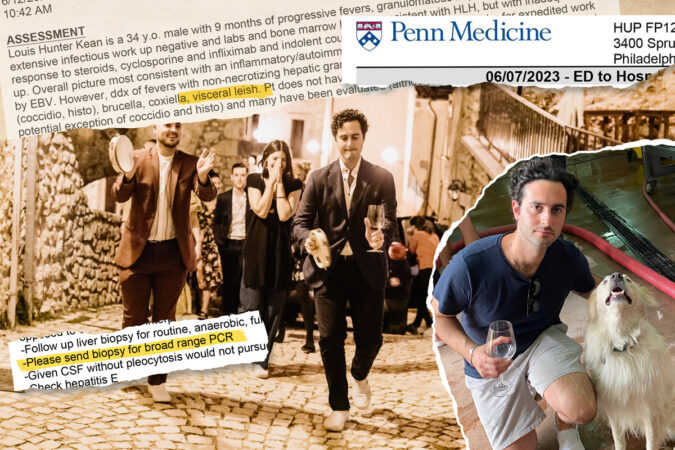

Each night, Louis-Hunter Kean spiked a fever as high as 104.5. He would sweat through bedsheets and shiver uncontrollably. By morning, his fever would ease but his body still ached; even his jaw hurt.

He had been sick like this for months. Doctors near his South Jersey home couldn’t figure out why a previously healthy 34-year-old was suffering high fevers plus a swollen liver and spleen. In early 2023, they referred Kean to Penn Medicine.

“These doctors are very sharp, and there are a lot of teams working on it,” Kean texted a friend after being admitted to the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP) in West Philadelphia.

Was it an infection? An autoimmune disease? A blood cancer? Over the next six months, at least 34 HUP doctors — rheumatologists, hematologist-oncologists, gastroenterologists, infectious disease and internal medicine specialists — searched for an answer.

Kean was hospitalized at HUP five times during a six-month period in 2023. His electronic medical chart grew to thousands of pages.

Along the way, doctors missed critical clues, such as failing to obtain Kean’s complete travel history. They recommended a pair of key tests, but didn’t follow up to make sure they got done, medical records provided to The Inquirer by his family show.

Doctors involved in Kean’s care, including at Penn, prescribed treatments that made him sicker, said four infectious disease experts not involved in his care during interviews with a reporter, who shared details about his treatment. Penn doctors continued to do so even as his condition worsened.

“No one was paying attention to what the doctor before them did or said,” Kean’s mother, Lois Kean, said.

“They did not put all the pieces together,” she said. “It was helter-skelter.”

Kean’s family is now suing Penn’s health system for medical malpractice in Common Pleas Court in Philadelphia. The complaint identifies nearly three dozen Penn doctors, accusing them of misdiagnoses and harmful treatments. These physicians are not individually named as defendants.

In court filings, Penn says its doctors did not act recklessly or with disregard for Kean’s well-being, and his case is not indicative of any systemic failures within its flagship hospital. A Penn spokesperson declined further comment on behalf of both the hospital and the individual doctors involved in Kean’s care, citing the pending lawsuit.

The puzzle of Kean’s diagnosis finally came together in November 2023 after a Penn doctor, early in his career, sought help from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

An NIH doctor recommended a test that identified the cause: a parasite prevalent in countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Kean likely got infected while vacationing in Italy, four parasitic disease experts told The Inquirer.

The infection, which is treatable when caught early, is so rare in the U.S. that most doctors here have never seen a case, the experts said.

By the time Penn doctors figured it out, Kean’s organs were failing.

A missed clue

When a patient has an ongoing and unexplained fever, an infectious disease doctor will routinely start by taking a thorough travel history to screen for possible illnesses picked up abroad.

A medical student took Kean’s travel history during his initial workup at HUP in June 2023. An infectious disease specialist reviewed the student’s notes and added a Cooper University Hospital doctor’s earlier notes into Kean’s electronic medical chart at Penn.

Those records show Kean had traveled to Turks and Caicos with his fiancée in May 2022. The next month, he took a work trip out West, including to California, where he visited farms, but didn’t interact with livestock.

This was not unusual for Kean, who worked with fruits and vegetables imported from around the world at his family’s produce distribution center on Essington Avenue in Southwest Philadelphia.

Kean’s fiancée, Zara Gaudioso, said she repeatedly told doctors about another trip: In September 2021, about a year before his fevers began, they traveled to Italy for a friend’s wedding in Tuscany.

The couple hiked remote foothills, danced all night in a courtyard, dined by candlelight surrounded by a sunflower farm, and slept in rustic villas with the windows flung open.

“We told everybody,” Gaudioso said. “A lot of Americans go to Italy — it’s not like a third-world country, so I could see how it could just go in one ear and out the other.”

But notes in Kean’s medical record from the Penn infectious disease specialist don’t mention Italy. Neither do the ones the specialist copied over from Kean’s infectious disease doctor at Cooper.

Kean “does not have known risk factors” for exposure to pathogens, the Penn specialist concluded, except possibly from farm animals or bird and bat droppings.

Still, the specialist listed various diseases that cause unexplained fever: Tick-borne diseases. Fungal infections. Tuberculosis. Bacteria from drinking unpasteurized milk.

The possible culprits included a parasitic disease, called visceral leishmaniasis, transmitted by a bite from an infected sandfly. It can lie dormant for a lifetime — or, in rare cases, activate long after exposure, so it’s important for doctors to take extensive past travel histories, parasitic experts say.

The parasite is widely circulating in Southern European countries, including Spain, Greece, Portugal, and Italy.

“Mostly, people living there are the ones who get it. But it’s just a lottery sandwich, and there’s no reason that travelers can’t get it,” said Michael Libman, a top parasitic disease expert and former director of a tropical medicine center at McGill University in Canada.

But few cases become severe. Hospitals in Italy reported only 2,509 cases of active infection between 2011 and 2016, affecting fewer than one in 100,000 people. Infections requiring hospital care in Italy began to decline after 2012, according a 2023 European study by the Public Library of Science (PLOS) journal Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Caught early, visceral leishmaniasis is treatable. Without treatment, more than 90% of patients will die.

In addition to fever, other telltale symptoms are swelling of the liver and spleen and low blood cell counts. Kean had all of those.

A missed test

The infectious disease specialist requested a test to examine tissue biopsied from Kean’s liver, which was damaged and enlarged. Lab results showed that immune cells there had formed unusual clusters — another sign that his body might be fighting off an infection.

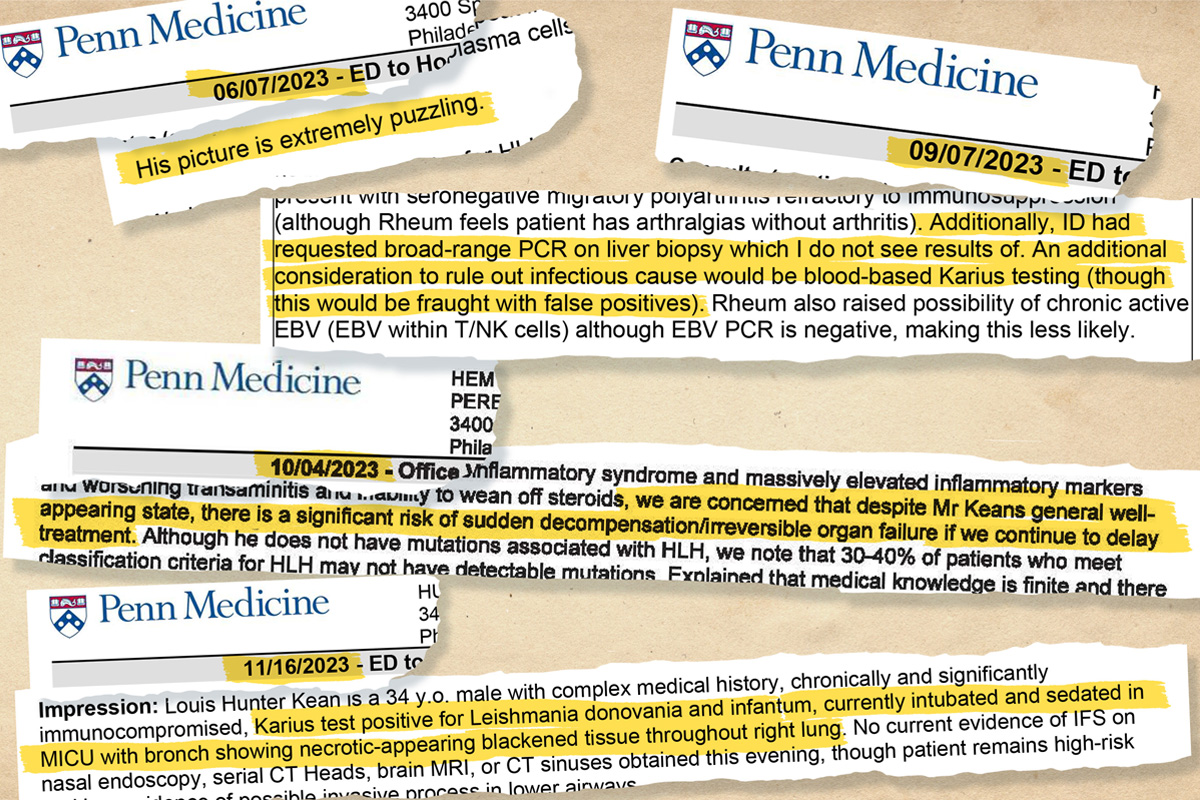

In her notes, the specialist identified “visceral leish” as a possible diagnosis, which repeated — via copy and paste — seven times in his medical record. Her request to “please send biopsy for broad-range PCR” repeated five times.

That is a diagnostic (polymerase chain reaction) test that looks for the genetic fingerprint of a range of pathogens.

The test comes in different versions: One looks broadly for bacteria. The other is for fungi. The broad fungal test can detect leishmania, even though it’s not a fungus. However, it’s not always sensitive enough to identify the parasite and can produce a false negative, experts said.

The specialist’s chart note doesn’t specify which type she wanted done.

It’s not clear if anyone asked. The test wasn’t done.

She did not order a low-cost rapid blood test that screens specifically for leishmaniasis by detecting antibodies made by the immune system after fighting it. She also didn’t order a leishmania-PCR, which is highly targeted to detect the exact species of the parasite.

Nor did the medical record show that the specialist followed up on the results of the broader test she requested, even though she saw Kean on nine of the 13 days of his first hospitalization at HUP in June 2023.

Penn has a policy that a lead doctor on the patient’s case is responsible for making sure that recommended tests get done. The specialist was called in as a consultant on Kean’s case. During that June hospitalization alone, his medical chart grew to 997 pages.

Patient safety experts have warned for years that electronic medical record systems — designed for billing and not for care — can become so unwieldy that doctors miss important details, especially with multiple specialists involved, or repeat initial errors.

A seemingly innocuous step in charting — copying and pasting previous entries and layering on new ones — can add to the danger, patient safety experts say.

That’s how the specialist’s mention of “visceral leish” and her test recommendation got repeated in Kean’s chart.

Marcus Schabacker, president of ECRI, a nonprofit patient-safety organization based in Plymouth Meeting, said “copy and paste” in electronic medical records puts patients at risk of harm.

“The reality is if you are reading something over and over again, which seems to be the same, you’re just not reading it anymore. You say, ‘Oh, yeah, I read that, let’s go on,’” said Schabacker, speaking generally about electronic medical record systems and not specifically about Kean’s case.

When treatments harm

Penn doctors believed Kean had a rare, life-threatening disorder, known as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), in which the immune system attacks the body. Instead of fighting infections, defective immune cells start to destroy healthy blood cells.

In most adults, the constellation of symptoms diagnosed as HLH gets triggered when an underlying disease sends the body’s immune system into overdrive. Triggers include a blood cancer like lymphoma, an autoimmune disease like lupus, or an infection.

Penn doctors across three specialties — hematology-oncology, rheumatology, and infectious disease — were searching for the cause within their specialties.

“His picture is extremely puzzling,” one doctor wrote in Kean’s chart. “We are awaiting liver biopsy results. I remain concerned about a possible infectious cause.”

As HUP doctors awaited test results, they treated Kean’s HLH symptoms with high doses of steroids and immunosuppressants to calm his immune system and reduce inflammation.

The treatments, however, made Kean highly vulnerable to further infection. And defenseless against another possible trigger of HLH: visceral leishmaniasis.

At the time, a Penn rheumatologist involved in Kean’s care before his first hospitalization warned about steroids “causing harm” to Kean if it turned out he had an infection. He wrote, “please ensure all studies requested by” infectious disease are done, medical records show.

Steroid treatments would allow the parasites to proliferate unchecked, experts said.

“It’s unfortunately exactly the wrong treatment for parasitic disease,” said Libman, the leishmania disease expert at McGill University.

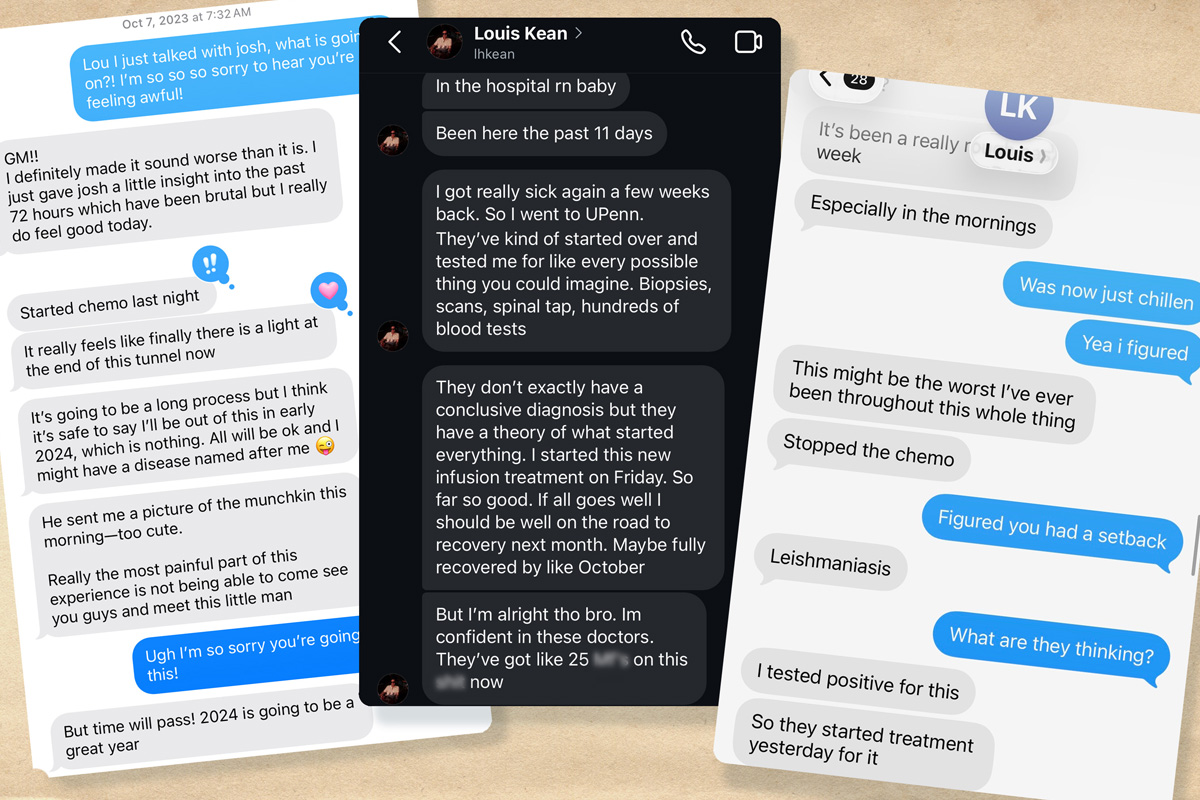

As Kean grew sicker, he was readmitted to HUP for a third time in September 2023. He texted a friend: “I’m on more medications than I’ve ever been on and my condition is worse than it’s ever been.”

Handoffs between doctors

No single doctor seemed to be in charge of Kean’s care, his family said. And the number of specialists involved worried them.

“Everyone just kept being like, ‘We don’t know. Go see this specialist. Go see that specialist,’” Kean’s sister, Priscilla Zinsky, said.

By fall 2023, rheumatologists hadn’t found a trigger of Kean’s symptoms within their specialty. They turned to doctors specializing in blood cancer.

During the handoff, three doctors noted that they didn’t see the results of the test requested by the infectious disease specialist back in June. They still thought it was possible that Kean had an infection, records show.

One blood disorder specialist now suggested an additional test that screens for more than 1,000 pathogens, including leishmania.

“An additional consideration to rule out infectious cause would be blood-based Karius testing (though this would be fraught with false positives),” wrote that doctor, who was still training as a hematologist-oncologist.

A supervising physician reviewed the Sept. 8, 2023, note and signed off on it. The medical records don’t show any follow-up with infectious disease doctors, and the test wasn’t done at the time.

In the coming days, blood cancer specialists struggled to find a link between Kean’s symptoms and an underlying disease.

They thought he might have a rare form of leukemia, but tests weren’t definitive, Kean texted friends.

Untreated HLH symptoms can lead to rapid organ failure, so doctors often start patients on treatment while trying to figure out the underlying cause, said Gaurav Goyal, a leading national expert on HLH, noting that it can take days to get test results.

“You have to walk and chew the gum. You have to calm the inflammation so the patient doesn’t die immediately, and at the same time, try to figure out what’s causing it by sending tests and biopsies,” said Goyal, a hematologist-oncologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Medical records show that Penn doctors feared Kean was at “significant risk” of “irreversible organ failure.”

They suggested a more aggressive treatment: a type of chemotherapy used to treat HLH that would destroy Kean’s malfunctioning immune cells.

In his medical record, a doctor noted that beginning treatment without a clear diagnosis was “not ideal,” but doctors thought it was his best option.

Four parasitic disease experts told The Inquirer that chemotherapy, along with steroids and immunosuppressants, can be fatal to patients with visceral leishmaniasis.

“If that goes on long enough, then they kill the patient because the parasite goes out of control,” Libman said, explaining that ramping up the HLH treatments weakens the immune system. “The parasite has a holiday.”

Chemo as last resort

Kean banked his sperm, because chemo infusions can cause infertility. He told friends he trusted his Penn team and hoped to make a full recovery.

“Started chemo last night. It really feels like finally there is a light at the end of the tunnel,” he texted a friend on Oct. 7, 2023.

“I’m gonna get to marry my best friend, and I think I’m going to be able to have children,” Kean wrote in another text to a different friend.

Kean spent nearly all of October at HUP getting chemo infusions. He rated his pain as a nine out of 10. His joints throbbed. He couldn’t get out of bed. He started blacking out.

Doctors added a full dose of steroids on top of the IV chemo infusion. By the end of the month, Kean told a friend he feared he was dying.

A year had passed since Kean first spiked a fever. He no longer could see himself returning to his former life — one filled with daily exercise, helping run his family’s produce store, nights out with friends at concerts and bars, and vacations overseas.

Lethargic and weak, he could barely feed himself. His sister tried to spoon-feed him yogurt in his hospital bed.

He started texting reflections on his life to friends and family, saying his illness had given him a “polished lens” through which he could see clearly. He wrote that their love felt “like a physical thing, like it’s a weighted blanket.”

“I’ve lived an extremely privileged life. I don’t think it’s possible for me to feel bad for myself,” he said in a text. “And I don’t want anyone else to either.”

Puzzle solved

One doctor involved in Kean’s care had seen him at Penn’s rheumatology clinic in early June 2023, just before his first HUP hospitalization. The doctor, a rheumatology fellow, urged him to go to HUP’s emergency department, so he could be admitted for a medical workup.

The fellow remained closely involved in Kean’s care, medical records show. Also in his 30s, this doctor shared Kean’s interests in music, fashion, and the city’s restaurant scene, according to Kean’s family.

“They had a rapport,” Kean’s father, Ted Kean, said. “Louis thought a lot of him, and he seemed to think a lot of my son.”

By early November 2023, the rheumatology fellow was extremely concerned, medical records show.

The chemo infusions weren’t helping. Kean still was running a fever of 103. The fellow wrote in his chart that he was worried Kean needed a bone-marrow transplant to replace his failing immune system.

And doctors still didn’t know the root of his symptoms.

The fellow contacted the NIH, medical notes show.

An NIH doctor recommended a test to check for rare pathogens, including parasites that cause visceral leishmaniasis, according to family members present when the testing was discussed.

The NIH-recommended Karius test was the same one suggested two months earlier by the Penn hematologist-oncologist in training, but with no follow-up.

On Nov. 16, the fellow got the results. He went to Kean’s bedside.

After five HUP hospitalizations over six months, a single test had revealed the cause of his illness: visceral leishmaniasis.

Kean cried with relief and hugged the fellow, joined by his mother and sister.

“‘You saved my life,’” Kean’s sister, Jessica Kean, recalled her brother telling the doctor. “‘Finally, we know what this is, and we can treat it.’”

To confirm the results, Penn sent a fresh blood sample from Kean to a lab at the University of Washington Medical Center for a targeted and highly sensitive leishmania-PCR test created by pathologists there.

Kean’s medical chart was updated to note that he traveled to “Italy in the past,” also noting he had visited Nicaragua and Mexico. A HUP infectious disease doctor consulted with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on antiparasitic medications.

Meanwhile, Kean’s nose wouldn’t stop bleeding. He felt light-headed and dizzy, with high fever. Even on morphine for his pain, his joints ached.

“I’ve been struggling, buddy,” he texted a friend on Nov. 20. “This might be the worst I’ve ever been.”

By Nov. 22, he stopped responding to text messages. He began hallucinating and babbling incoherently, family members recalled. “Things went downhill very, very quickly, like shockingly quickly,” his sister, Priscilla Zinsky, said.

When she returned on Thanksgiving morning, he was convulsing, thrashing his head and arms. “It was horrifying to see,” Zinsky said.

Her brother had suffered brain bleeds that caused a stroke. His organs were failing. He had a fungal infection with black mold growing throughout his right lung, medical records show.

Kean was put on life support, with a doctor noting the still-preliminary diagnosis: “Very medically ill with leishmaniasis.”

“Prognosis is poor,” read the note in his Nov. 29, 2023, medical records.

A few hours later, Kean’s family took him off life support. He died that day.

“All of his organs were destroyed,” said Kean’s mother, Lois Kean. “Even if he had lived, he had zero quality of life.”

Post mortem

The day after his death, HUP received confirmation from the Washington state lab that Kean had the most deadly species of leishmania, medical records show.

It’s not clear why the parasites began to attack Kean a year after his return from Italy. Healthy people rarely develop severe disease from exposure to the deadly form of the parasite circulating outside the U.S., experts said.

Most people infected by a sandfly “are probably harboring small amounts of the parasite” in their organs, according to Naomi E. Aronson, a leishmania expert and director of infectious diseases at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md.

“Most of the time, you don’t have any problem from it,” Aronson said.

Children under age 5, seniors, and people who are malnourished or immunodeficient are most susceptible to visceral leishmaniasis. Aronson said she worries about people who might harbor the parasite without problems for years, and then become immunocompromised.

Libman, the parasitic expert from McGill, said he’s seen six to 10 patients die from visceral leishmaniasis because doctors unfamiliar with the disease mistakenly increased immunosuppressants to treat HLH during his 40 years specializing in parasite disease.

“That’s a classic error,” he said.

Kean’s case “should be a real clarion call” for infectious disease specialists and other doctors in the U.S., said Joshua A. Lieberman, an infectious disease pathologist and clinical microbiologist who pioneered the leishmania-PCR test at the Washington state lab.

“If you’re worried about an unexplained [fever], you have to take a travel history that goes back pretty far and think about Southern Europe, Iraq, Afghanistan, India, and maybe even Brazil,” Lieberman said.

In the wake of Kean’s death, his family was told that Penn doctors held a meeting to analyze his case so they could learn from it.

An infectious disease doctor called Zinsky, Kean’s sister, to let her know about the postmortem review and shared that doctors discussed that Kean had likely picked up the parasite in Tuscany.

“Why didn’t you guys have this meeting,” she asked, ”while he was alive?”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to clarify that ECRI President Marcus Schabacker was not speaking specifically on Kean’s case.