When Mayor Cherelle L. Parker unveiled her much-anticipated plan to address Philadelphia’s housing crisis last year, there was predictable criticism from the political left. Activists said the proposal drafted by the moderate Democrat would not do enough for the city’s poorest residents.

Less predictable was that a majority of City Council stood with them.

Even the Council president, a centrist ally of the mayor, sided with a progressive faction that just two years ago had been soundly defeated in the mayor’s race — but whose new de facto leader in City Hall has proven adept at building alliances across the ideological spectrum.

At the center of that shift was Jamie Gauthier.

The second-term Democratic lawmaker from West Philadelphia has solidified herself over the last year as a leading voice on Council and a counterweight to Parker. She has worked within the system as opposed to trying to break it, maintaining relationships with power players who disagree with her on policy.

She counts Ryan N. Boyer — the labor leader who is Parker’s closest political ally — among those who consider her a “thought leader.”

“Over the last year, what you saw,” Boyer said, “is her modulate her positions to become more practical.”

Gauthier has generally voted with progressives, including last year when she opposed the controversial Center City 76ers arena proposal. But she has also endeavored to be a team player, at times compromising on ideological battles to focus on priorities in her district.

Last year, she voted for Parker’s plan to cut taxes for businesses and corporations when other progressives opposed it, because her main priority was securing housing funding. She has not opposed some tough-on-crime efforts in the Kensington drug market, instead allowing her colleagues who represent that area to dictate the policy there.

She says she is trying to use her political capital where it matters.

“Why would I take a protest vote and tank a relationship with a colleague when I’m going to need them later?” she said. “I want to win.”

The fact that Gauthier is a district Council member who represents a large swath of the city west of the Schuylkill also gives her cachet with colleagues. Council has a long tradition of honoring how members want their own neighborhoods to be governed.

Gauthier, who leads Council’s housing committee, has used the influence to make West Philadelphia something of a testing ground for left-of-center policy. Plenty oppose what they see as draconian restrictions on real estate development in her district.

Others see a progressive champion, and some political observers think Gauthier could amass enough support to run for mayor one day. She doesn’t deny that she has thought about it.

But for whatever politics Gauthier can navigate in City Hall, she knows she can rise only if she is successful at home.

‘Not just a lone actor’

When Parker took office, Council was in a moment of upheaval. Council President Kenyatta Johnson was the new leader of the chamber, and several prominent voices were gone after they had resigned to run for mayor themselves.

One was Helen Gym, who was seen as the leader of Council’s left flank. There were questions about who would fill the void once Gym was gone.

Gauthier, 47, an urban planner by trade, did not come up through an activist movement in the same way Gym did, and was a bit more reserved in her style.

But she carries the mantle for the same theory of governance: that lawmakers should prioritize the vulnerable, and that what is good for business is not necessarily good for everyone else.

That set Gauthier on an ideological collision course with Parker, a former Council member who ran for office on a promise to uplift the middle class, a group the mayor believes has been too often ignored.

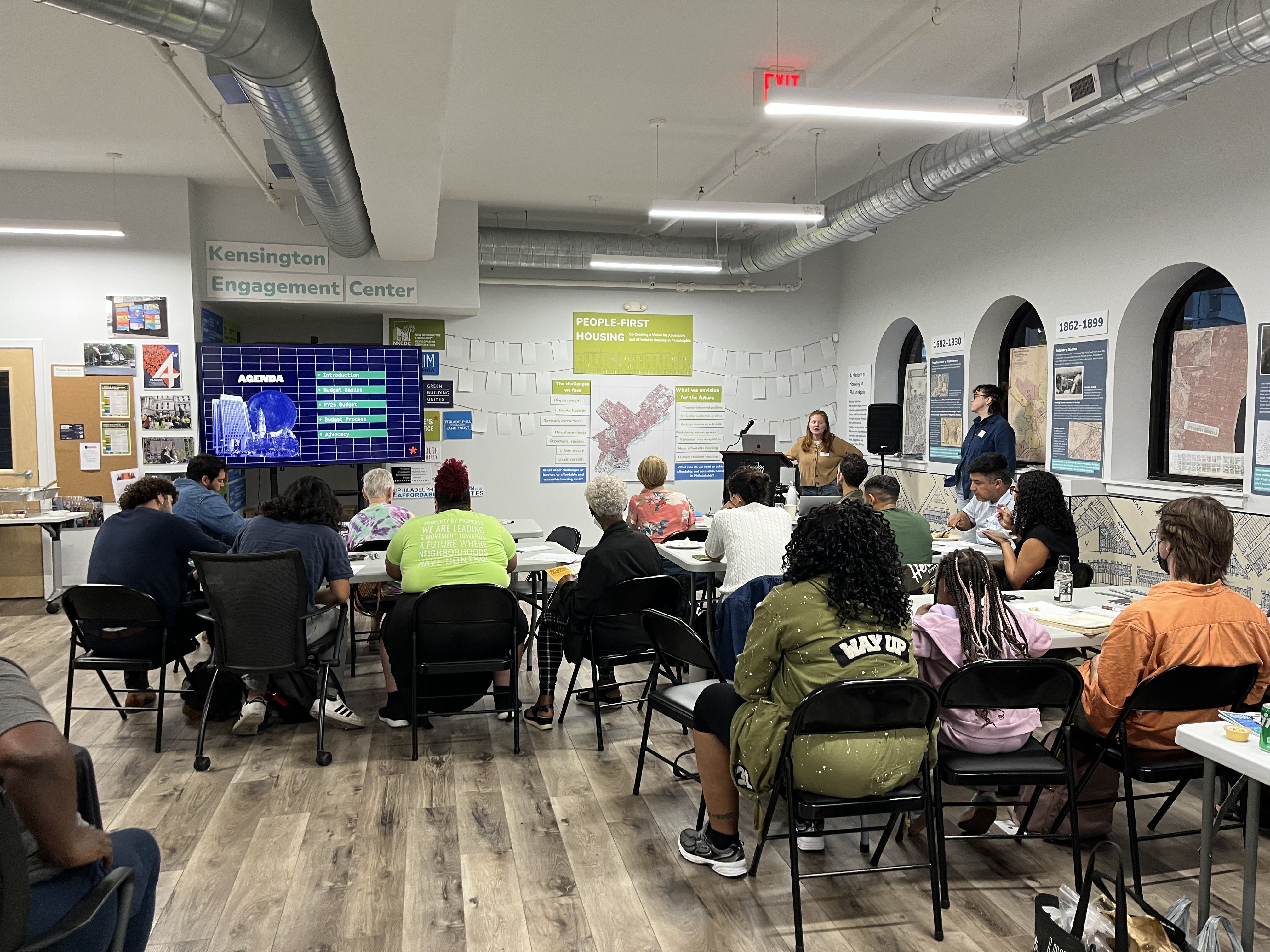

It came to a head in the fight over Parker’s Housing Opportunities Made Easy, or H.O.M.E., initiative.

Parker wanted to set unusually high income eligibility thresholds for some of the programs so that middle-class families could unlock government subsidies they may not otherwise qualify for. A significant portion of Council, meanwhile, wanted the money to go initially to Philadelphians most vulnerable to displacement.

Parker was clear-eyed about who was leading the charge.

“Councilmember Jamie Gauthier, she may be comfortable and OK with telling Philadelphia homeowners, working-class Philadelphians, that they have to wait and there is no sense of urgency for them,” Parker said in a December interview on WHYY. “But that is not a sentiment that I support or agree with.”

Gauthier is quick to point out that she did not work alone, and that one member of a 17-member body cannot accomplish much. Alongside Councilmember Rue Landau, a fellow Democrat and a housing attorney by trade, Gauthier worked for months to win over her colleagues.

In the end, Council approved a version of the housing initiative closer to Gauthier’s vision.

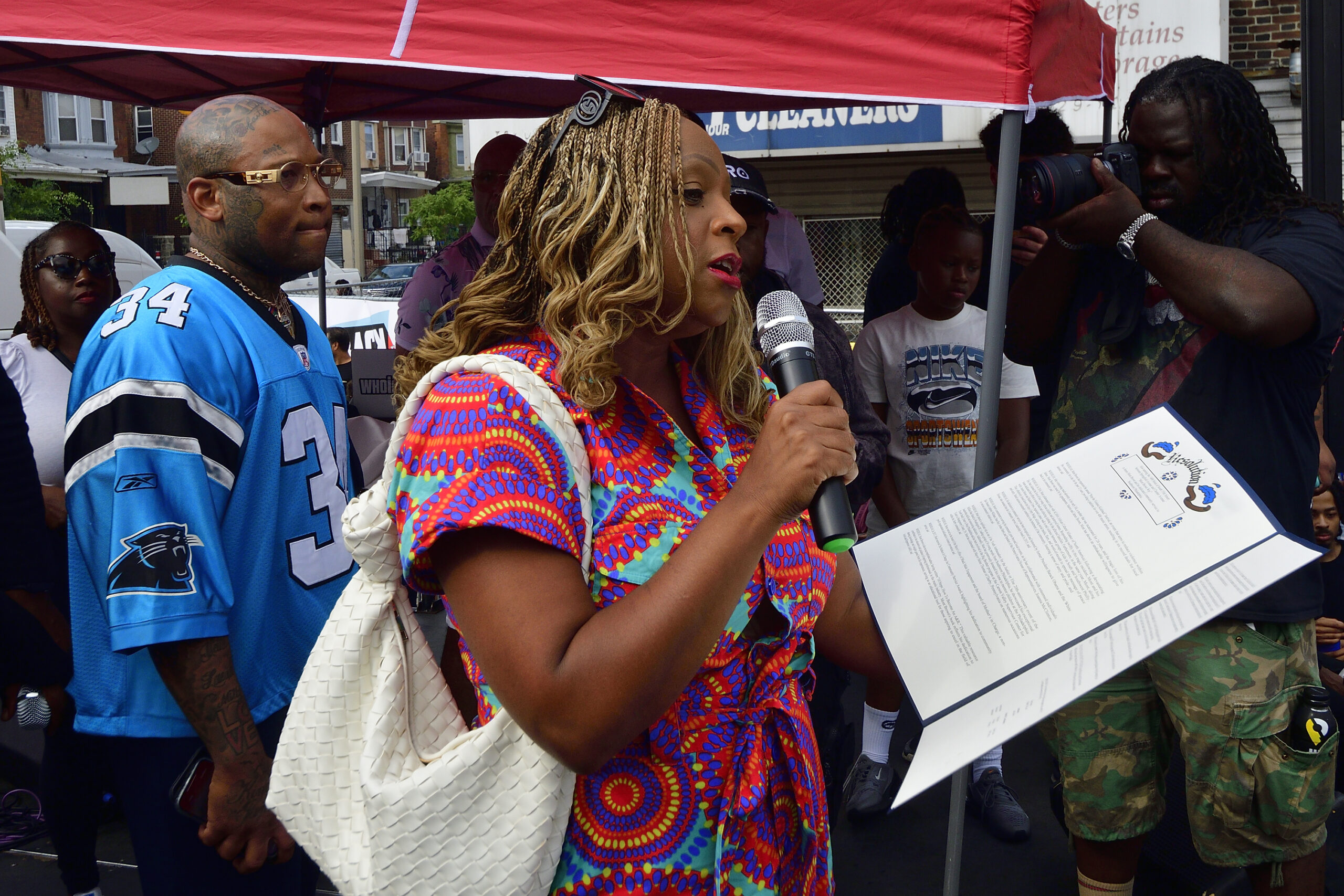

Gauthier didn’t think Parker helped her own cause. A “line was crossed,” she said, when Parker took the fight outside City Hall and to the pulpit. Amid negotiations with Council, the mayor went to 10 churches on one Sunday in December to lobby for support, saying her vision was to not “pit the ‘have-nots’ against those who have just a little bit.”

To Gauthier, the divisiveness was coming from the mayor’s office.

“I wish the mayor and her administration were more open to other people’s ideas, were more OK with disagreement on policy issues, and more aware of Council as a completely separate chamber of government,” Gauthier said, “as opposed to a body that works for her.”

That is a candid assessment of the relationship between Parker and City Council from Gauthier. Few lawmakers from the mayor’s own party have criticized her publicly.

State Rep. Rick Krajewski, a West Philadelphia Democrat and a progressive who has worked closely with Gauthier, said the fight over H.O.M.E. showed that Gauthier has learned “the diplomacy required to be an effective legislator.”

“It was a good example of not being afraid of a conflict that felt important to stand up for,” he said, “but then to not just be a lone actor, but organize with other colleagues and allies.”

Gauthier’s most important ally was Johnson, who negotiated directly with Parker through the process and controls the flow of legislation in the chamber.

The two go back years. Before Johnson was Council president, he made a point of welcoming new members, a gesture that has always stuck with Gauthier. They worked closely to secure funding for gun violence prevention. And Gauthier said that since Johnson took the gavel, he has been more open to working with progressives than his predecessor was.

She was also key to Johnson’s ascent. When he was locked in a tight battle for the Council presidency, it was Gauthier who became the ninth Council member to commit to voting for Johnson, allowing him to secure a majority of members and the presidency.

He does not talk about that publicly. What he will say is that he works in partnership with Gauthier because she understands “the bigger picture in terms of how we move forward as the institution.”

“I consider her to be a pragmatic idealist,” Johnson said. “She wears her heart on her sleeve, and she really believes in actually doing the work.”

Creating a testing ground in West Philly

When Gauthier first ran for office in 2019 against a member of one of Philadelphia’s most entrenched political families, she ran as a good-government urbanist. She railed against councilmanic prerogative, the city’s long tradition of allowing district Council members final say over land-use decisions in their areas.

She was also supported by real estate interests, some of whom now have buyer’s remorse.

After Gauthier pulled off a shock win, she arrived in Council and quickly aligned with the progressive bloc. Through her first two terms, she has used councilmanic prerogative often, and has voted with her district Council colleagues so that they can do the same.

She admits that it is an effective tool for accomplishing her goals quickly.

Carol Jenkins, a Democratic ward leader in West Philadelphia, said Gauthier’s use of councilmanic prerogative is “part of her maturation.”

“That’s the power you have,” Jenkins said.

Gauthier has at times used the power in ways that the city’s urbanists and development interests can get behind. She has quickly approved bike lane expansions. And she recently was the only district Council member to allow her entire district to be included in legislation that cuts red tape for restaurants that want to offer outdoor dining.

However, her most notable use of councilmanic prerogative has been in housing policy, and some developers say her district is now the most hostile to growth in the city.

In Gauthier’s first term, she championed legislation to create what is known as a Mixed Income Neighborhood overlay. In essence, it requires that developers building projects with 10 or more units in certain parts of her district make at least 20% of their units affordable. That is defined as accessible for rental households earning up to 40% of the area median income.

For Gauthier, it’s a tool to slow the rapid gentrification of her majority-Black district.

But developers say that growth has slowed significantly in the areas covered by the overlay since it took effect in 2022. Some have said they avoid seeking to build in the 3rd District entirely. The only major project currently in the works in the area is a parking garage.

Ryan Spak, an affordable housing developer who said he considers Gauthier a friend, has been among the most outspoken critics of the overlay. He said while Gauthier’s “moral compass is pointed in the right direction, her policies don’t math.”

“You would never ask a restaurant to give away its ninth and 10th meal for 40 cents on the dollar, with no additional discounts or benefits,” he said, “and expect that restaurant to survive.”

Gauthier said she has made adjustments, and she championed legislation to accelerate permitting and zoning approvals. The mandate, she said, is necessary because the market won’t build enough affordable housing on its own.

“As untenable as it is to them that they can’t make the numbers work, it’s untenable to me that people can’t afford to live here,” Gauthier said. “So we can come together and we can fix that. But I’m not going to move from my position that we have to demand affordability.”

Mayoral buzz, but no ‘stupid campaigns’

Gauthier is one of several names that have been floated in political circles as potential candidates for mayor in 2031, which would be Parker’s final year in office if she runs for and wins a second term. Several of her Council colleagues, including Johnson, are seen as potential contenders.

“I’d be lying if I didn’t say that mayor could be interesting one day,” Gauthier said. “I also don’t believe in stupid campaigns. So I would never do that if I didn’t think I had a path.”

Boyer said he has counseled Gauthier to pursue moderate policy and avoid being “label-cast” as far left. He said Philadelphia is not Chicago or New York, and he doesn’t see the city electing an uber-progressive to be the mayor any time soon.

“Philadelphia has always been a real center-left community,” Boyer said, “and just because you’re the loudest isn’t the most popular.”

The left may have other plans. Robert Saleem Holbrook, a progressive activist, said that Gauthier would be an “ideal candidate” for higher office and that the city’s leftists would back her.

Probably.

“So long as she stays true and supportive of progressive ideals,” Holbrook said. “You can’t compromise on your way up.”