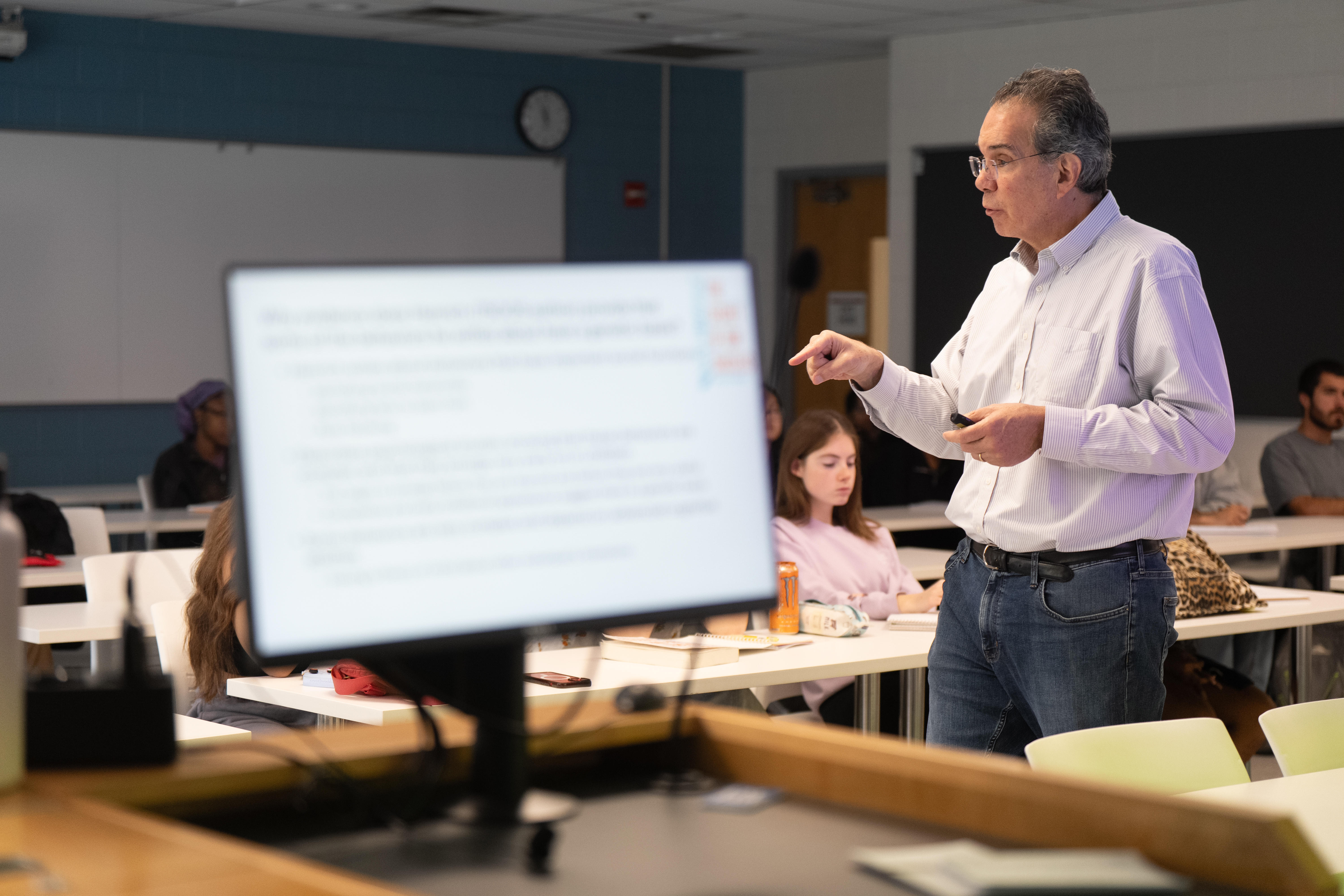

Biology professor Jody Hey was lecturing on human evolution one recent day at Temple University.

His students vigorously took notes by hand in paper notebooks.

There wasn’t a laptop in sight. Nor an iPhone. No student’s face was hidden by a screen.

Hey said he stopped allowing them about a year and a half ago after seeing research that students are too often distracted when laptops are open in front of them and actually learn better when they have to distill lectures into handwritten notes.

“The clearest sign that it’s making a difference is that students are paying attention more,” said Hey, who has taught at Temple for more than 12 years. “And they want to participate much more than before.”

Hey is among a seemingly growing number of professors who have chosen to keep laptop and phone use out of class, with exceptions for students with disabilities who require accommodations. Several said they made the decision after seeing what some students were doing on their laptops during class.

Jessa Lingel, an associate professor of communication at the University of Pennsylvania and director of the Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Program there, stationed teaching assistants in the back of her room to observe.

Students “were out there booking flights and Airbnbs,” Lingel said. “Fun fall cocktail recipes. They were online gambling in class. I thought, ‘This is not acceptable.’”

She originally disallowed laptops in 2017, but decided to go easy in 2021 as students returned after the pandemic, she said. She reinforced the ban after her teaching assistants’ observations.

“It’s a movement,” Lingel said. “More and more people are headed in this direction.”

In Hey’s class, students have warmed up to the laptop ban.

“At first I didn’t like it,” said Jess Nguyen, 20, a junior genomic medicine major from Broomall, “because I kind of organize all my notes on my laptop. But I feel I’ve been learning better by writing my notes.”

When she took notes on her iPad, she sometimes got distracted and played computer games, she said. In Hey’s class, that’s not an option.

Students said it takes more time to write notes and sometimes their hands get tired.

“After a couple classes, you kind of get used to it,” said Sara Tedla, 22, a senior natural sciences major from Philadelphia.

She’s on the fence about which way she prefers to take notes.

“It’s good that for an hour and 20 minutes you can just sit down and, without any technological distractions, focus because that’s a part of your brain you can work on,” said Quinn Johnson, 20, a senior ecology major from Philadelphia. “The more you do it, the easier it becomes to focus on something for a long period of time.”

‘Students learn better’

Professors say laptops are pretty ubiquitous in the classroom when they are permitted.

Hey conducted research on laptop use and presented it at a Temple department faculty meeting earlier this year.

“As early as 2003, a study was done contrasting the retention of lecture material by two groups of students, one who had laptops and unrestrained internet access and a second who worked without laptops,” he said. “In that study, students with laptops scored 20% lower on average in the subsequent exam.”

Four of every five students who used laptops in a general psychology class said they checked email during lectures, another study showed, while 68% used instant messaging, 43% surfed the net, 25% played games, and 35% said they did “other” activities.

He also cited studies showing students who took notes by hand performed better on tests. Others cited that research, too.

“I read the literature on it and it really showed that students learn better when they’re taking notes rather than trying to type as fast as they can verbatim what you say,” said Amy Gutmann, Penn president emerita, who is co-teaching a class at the Annenberg School for Communication this fall.

Gutmann and co-teacher Sarah Banet-Weiser, dean of Annenberg, do not provide students with copies of their lecture slides, either.

“We give them time to write down what’s on the slides,” Banet-Weiser said.

Benefits of technology

Some professors say laptop use in class can be beneficial.

Sudhir Kumar, a Temple biology professor, said he asks his class of 150 students to respond to questions on their laptops every 10 minutes. Their answers count toward their grades.

“It’s constantly keeping them on their toes,” he said.

He would not want to see everyone give up on laptop use in class.

“We cannot fight technology,” he said. “Teachers have to embrace technology, whether it is artificial intelligence or computers. That is a standard mode of operation for most people today.”

In Cathy Brant’s social studies methods class of 20 to 25 students at Rowan University, laptops are key. Brant, an associate professor of education, said there are lots of hands-on group projects, and she frequently asks students to check New Jersey standards online as they prepare their lessons. She also teaches them how to use AI appropriately in the classroom.

One of her students, she said, recently handed in a paper with very detailed notes from Brant’s lecture that she probably got only because she was able to type quickly on her computer.

“You’re responsible for paying attention in class,” she said. “Maybe it’s a little harsh, but I’m just like, ‘If you want to be on Facebook the entire time during class, that’s on you.’”

Jordan Shapiro, an associate professor at Temple, more than a decade ago used to make a point of having his students post on Twitter, now X, during class and counted it toward classroom participation.

Now, he tells students to put their laptops away during class.

“I tell them I have no problem with tech or laptops,” he said. “I just think that none of us get enough time in our lives to just focus on ideas or to listen in a sustained way to the people around us.”

He also became concerned about students doing homework during class, he said, and using artificial intelligence to supply them with questions and comments to ask in class. They were “outsourcing class participation to the robots,” he said.

Mark Boudreau, a biology professor at Penn State Brandywine, disallowed laptops for the first time this semester.

“I thought I would get real pushback … or people might even drop the class,” he said. “But … a lot of students have had other faculty who have this policy.”

Exam scores in his three courses are better this year, he said.

Hey noted student grades have gone up, too. But he can tell some students struggle with note-taking; some just listen and don’t take notes.

“That’s better than sitting there and going on Facebook,” he said.