For nearly a century, the Samuel Pennypacker School has survived — a three-story brick anchor of the West Oak Lane neighborhood in Northwest Philadelphia.

Now it faces the threat of extinction.

The Philadelphia School District says the school’s building score is “unsatisfactory” and modernizing it would cost more than $30 million. District officials are calling for shuttering Pennypacker following the 2026-27 school year, funneling its students to nearby Franklin S. Edmonds or Anna B. Day schools — part of a citywide proposal to close 20 district schools.

The recommendation, district officials say, is no reflection of the “incredible teachers, community, [and] students” at Pennypacker. Rather, it is an attempt by the district to optimize resources and equity for students.

Like many district schools, Pennypacker, which serves students in kindergarten through eighth grade, is aging and outdated, having opened in 1930. At just over 300 students, it is among the city’s smaller schools — and operating at about 64% of building capacity.

Yet, it is those same qualities — its size and longevity — that represent some of its greatest strengths, say those in the school community who are not happy about the proposed closure.

It’s a school, they say, that is more than the sum of its aging parts.

On the school’s walls are pocks of chipped paint, yes, but also the colorful detritus of a small but vibrant student population: a poster composed of tiny handprints in honor of Black History Month; a “Blizzard of Positivity” — handwritten messages reading “Smile” and “Hugs” and “Help your friends when they fall.”

It’s where Wonika Archer’s children enrolled soon after the family emigrated from Guyana — the first school they had ever known.

“A lot of firsts,” Archer said. “Their first friends, their first teachers outside of their parents.”

It’s where, since 1992, Andreas Roberts’ youth drill team has been allowed to practice. The team, which includes some Pennypacker students, recently participated in its first competition and won first place.

“Pennypacker has been very, very useful to us,” he said. “We have nowhere else to practice for the kids.”

It’s where Christine Thorne put her kids through school, her son and her daughter, and where her grandchildren now go. Around the school, they call her “Grandmama.”

“I feel as if my household is being destroyed,” she said recently.

For students, news of the imminent closure has been no less jarring.

When Janelle Pearson’s fourth-grade students learned recently that their school was poised to be shuttered under the district’s plan, they took it as a grim reflection on themselves.

“It makes them feel like, ‘What did we do wrong that they want to close our school?’” said Pearson, who has taught at Pennypacker for about a decade. “That’s the part that tugs at your heart.”

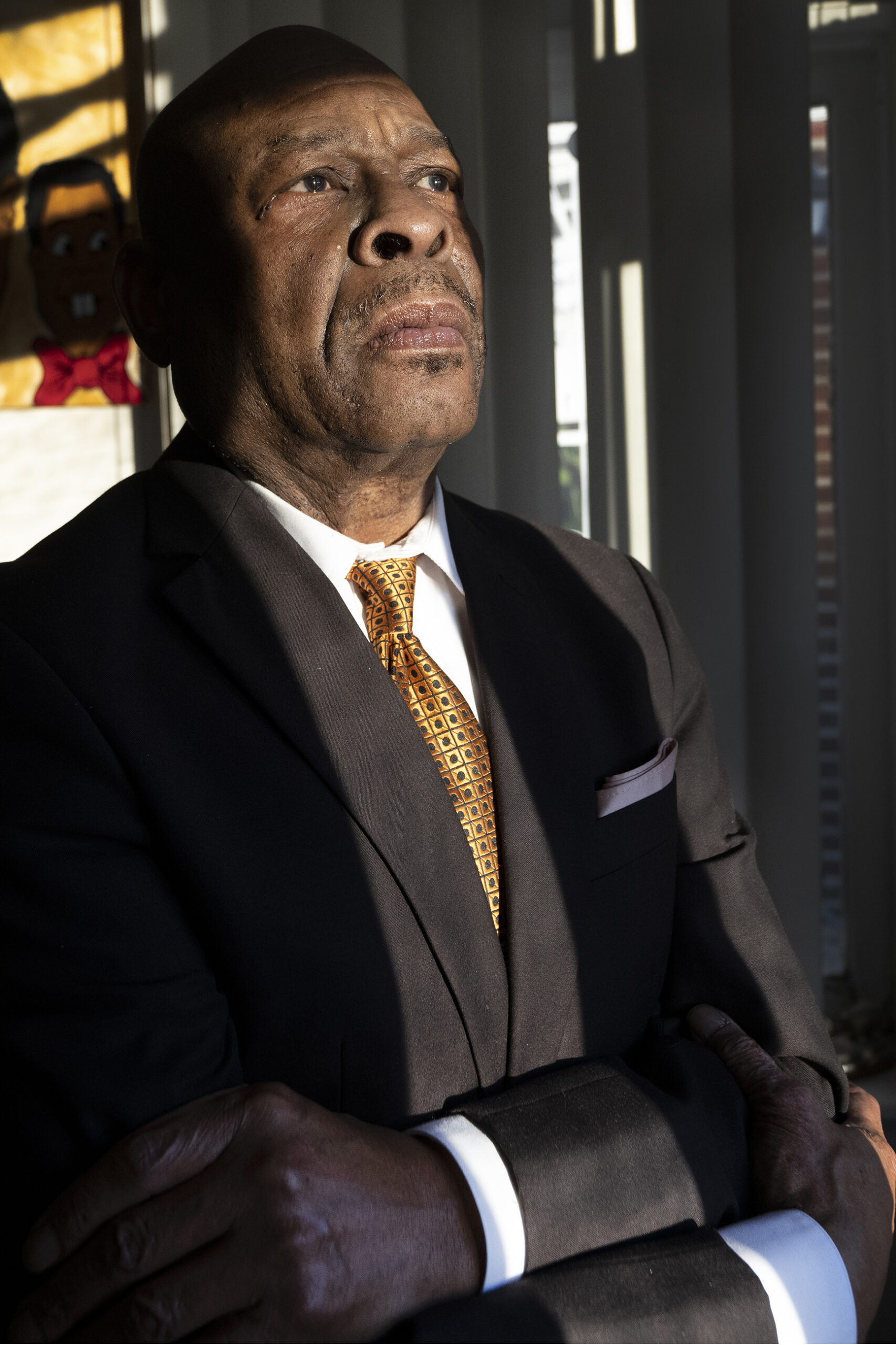

Unwilling to go down without a fight, the fourth graders resolved to do what they could. Soon, a poster took shape, in marker and crayon, a series of pleas addressed to Philadelphia Superintendent Tony B. Watlington Sr.

“Pennypacker is our home.”

“Don’t uproot our education.”

“Our neighborhood depends on this school!”

The poster was presented to district officials earlier this month at a community meeting held in the school’s wood-seated auditorium.

At that meeting, representatives from the district did their best to explain the reasoning for the proposed closures. They presented a tidy PowerPoint and talked of student retention and program alignment, of building capacity and neighborhood vulnerability scores.

It stood in stark contrast to the parents and teachers and staffers who, one by one, held a microphone and spoke of love and family and community, of teachers and staffers who routinely went above and beyond to make their children feel safe. To make them feel special.

“It’s not just about a building,” said Richard Levy, a onetime Pennypacker teacher who now works at St. Joseph’s University. “The challenges here aren’t reasons to close the school — they’re reasons to strengthen it.”

Whether their appeals might affect the district’s decision remains to be seen. Other schools in the district slated for closure have mounted efforts of their own, and, despite a recent grilling by City Council members, it seems all but certain that several schools will ultimately shutter.

A school board vote on the district’s proposal is expected later this winter.

Until then, those at Pennypacker are holding tight to the possibility of an eleventh-hour reprieve for the longtime neighborhood institution.

“I’m hoping there’s a chance,” Archer said. “I’m so hopeful.”