With a wad of chewing tobacco in his mouth, Curt Cignetti instructed the Temple quarterback to pause the VCR and stop the game tape from rolling. Cignetti, the Owls QB coach in the early 1990s, told the quarterback to hit rewind when he wanted to see something again.

The path to Monday night’s College Football Playoff national championship has taken Curt Cignetti, 64, all across college football. He worked his way from stops at schools like Indiana University of Pennsylvania and James Madison before becoming the head coach at Indiana, where he authored perhaps the most stunning turnaround in the history of the sport over the last two seasons.

That winding path came through North Philadelphia for four seasons as he was on Temple’s staff from 1989-92. He was young but he was intense, especially if you arrived late to that cramped office in McGonigle Hall, where a spittoon was always on the desk.

“We had some guys who came in like 15 minutes late and he was freaking hot,” said Matt Baker, Temple’s quarterback when Cignetti arrived.

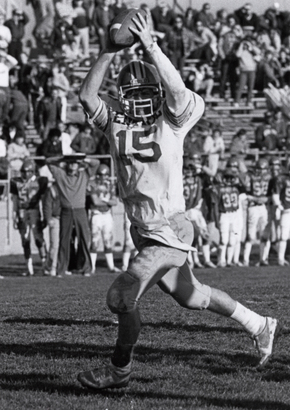

The Owls practiced on a piece of AstroTurf surrounded by North Philadelphia rowhouses and played Saturdays at an often-empty Veterans Stadium. Cignetti’s office did not have enough chairs for his quarterbacks — “Two of us were laying on the floor,” Dennis Decker said — and the TV didn’t even have a remote. He was a long way from college football glory.

“The only thing D1 about it was that we were playing D1 opponents,” said former offensive coordinator Don Dobes.

A basketball school

The Owls have had more gambling probes in the last 10 seasons than March Madness wins, but Temple was very much a basketball school when Cignetti arrived on North Broad Street in 1989.

Cignetti was just 28 when he came to Temple on the staff of Jerry Berndt, who was a Hall of Fame coach at Penn in the early 1980s before spending three seasons at Rice. Berndt was winless in his last season at Rice before replacing future Super Bowl champion Bruce Arians, who was fired after the Owls went 7-15 in his final two seasons while basketball dominated the landscape.

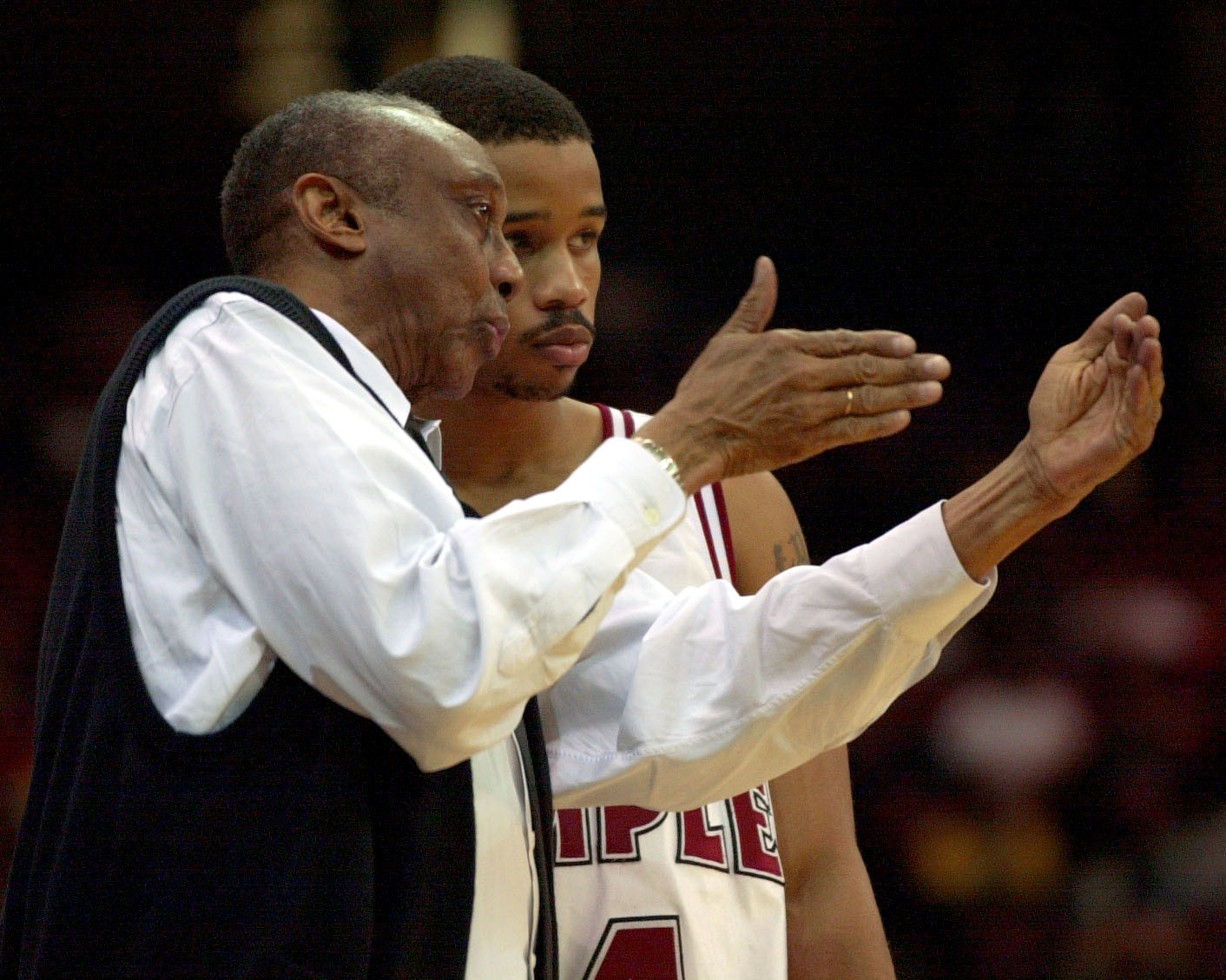

John Chaney was at his peak, and the Owls were ranked No. 1 during the 1988 season. Cignetti and the other football coaches often started their mornings watching Chaney run practice before sunrise.

“We’d get some wisdom before we went out there and practiced in the afternoon,” said Dobes. “You want to talk about a great teacher, a great motivator, the ability to impress upon people the importance of teamwork, and sacrifice, and character. That was John Chaney.”

Perhaps coaching football at a school where hoops was king was a precursor for what Cignetti did at Indiana, where he made a basketball-crazed campus fall in love with a sport that was often just an excuse to tailgate. The Hoosiers had the worst winning percentage in college football history before they hired Cignetti in November 2023. He took the microphone a few days later at a Hoosiers basketball game and boldly trashed IU’s rivals.

“He had a lot of [guts] saying that,” Baker said. “He’s the same guy now that he was back then.”

Cignetti retooled the Hoosiers through the transfer portal and reached the College Football Playoff last year in his first season. This year, the Hoosiers are 15-0 with a Heisman Trophy-winning quarterback in Fernando Mendoza, and enter Monday’s title game against Miami as favorites despite not having any five-star recruits. Cignetti was asked in December 2023 how he planned to sell his vision.

“It’s pretty simple,” the coach said. “I win. Google me.”

That was the coach the Temple guys remembered, a straight shooter who tended to be a tad quirky.

“I remember him questioning me after I threw a touchdown pass against Wisconsin,” Baker said. “He’s like, ‘Why’d you throw that?’ I said, ‘What? What do you mean?’ He said, ‘Did you see that?’ I said, ‘Yeah, in the pre-snap I saw he couldn’t cover [George] Deveney. He had a linebacker on him.’ He said, ‘Come on, Matt.’ I’m like, ‘What?’ It was just crazy things like that. We did a lot of good things.”

The same guy

The Owls won one game in Berndt’s first season before winning seven games in 1990 and gaining admission into the Big East. It was a win for a program that qualified for a bowl game that season but didn’t get picked because another school pledged to buy more tickets to the game.

The success was short-lived. The Owls missed out on local recruits — Dobes said he thought they had an in with Roman Catholic’s Marvin Harrison before he picked Syracuse — and announced their arrival to the Big East by winning three games in their first two seasons. The coaches knew the walls were closing in when they read the newspapers on the way to the airport in November 1992 for a game at No. 1 Miami.

“The headlines said ‘Berndt is burnt’,” Dobes said.

The Owls lost that game by 48 points, and when they arrived back in Philly, the coaches were informed that their season finale, just a few days away, would be their last game. They ended the 1992 season by dropping 10 straight.

“We were all in scramble mode at that point,” Dobes said.

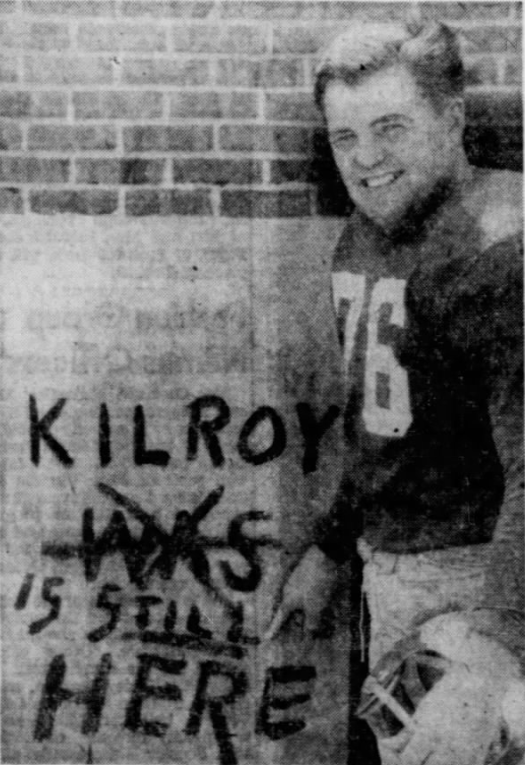

Cignetti, then just 31 years old, spent the next 14 seasons as an assistant at Pittsburgh and North Carolina State before spending four seasons under Nick Saban at Alabama. He often credits his time with Saban for his success. His first head-coaching gig was at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, the school an hour east of Pittsburgh, where his father had been the head coach from 1986 to 2005. Cignetti moved from IUP to Elon before landing at James Madison, where he reached the FCS national championship game and helped the Dukes transition to the FBS before being hired by the other Indiana University.

“There’s so many good coaches like him out there who never get a chance,” Dobes said. “He got a chance and made it happen.”

And there he was on New Year’s Day, beating Alabama by 35 points in the Rose Bowl. Decker, a teacher at Ridley High, told one of his coworkers that Cignetti was his coach 35 years ago. They couldn’t believe it. A few days later, the teacher’s old coach beat Oregon by 34 points to reach the national championship game. He’s the same guy, Decker said. Now, he has a remote control.

“Whoever was the low man on the totem pole had to stand up there and hit rewind, pause, play,” Decker said. “He was intense, but as a quarterback, you want that. You can’t be passive as a quarterback. He got his point across. He knew how to get his point across in the way he spoke to you. What that does is push yourself to bring the best out of you. You’re not going to be as successful as he is by being quiet and behind the scenes.”