Peter Fineberg sat in his Spectrum seats for more than 20 years, certain his perch was safe from the pucks that often flew into the stands. It would be years until protective netting was installed at every NHL arena, but Fineberg’s season tickets were behind the glass. He was good.

“The puck came in lots of times,” Fineberg said. “But always above me.”

But here it came — an errant slap shot in 1989 from a Flyers defenseman that redirected after tipping the top of the glass — falling straight onto Row 11 of Section L.

“We all see it coming,” Fineberg said. “I bail out of the way.”

He escaped, got back to his feet, and saw his mother grabbing her chin.

“I said, ‘Mom, what happened?’ She said, ‘The puck hit me,’” Fineberg said. “I go ‘What?’ She takes her hand off her chin and she just spurts blood.”

An usher walked Nancy Fineberg to a first-aid station where they helped slow the bleeding and offered the 64-year-old an ambulance ride to the hospital. But this was a playoff game and Nancy Fineberg, a mother of three who graduated from Penn in the 1940s, loved the Flyers. The stitches could wait.

“She said ‘I’ll go to the hospital after the game,” her son said. “She toughed it out.”

Another fan gave Nancy Fineberg a handkerchief to hold against her chin for the rest of the third period as the Flyers beat the Pittsburgh Penguins.

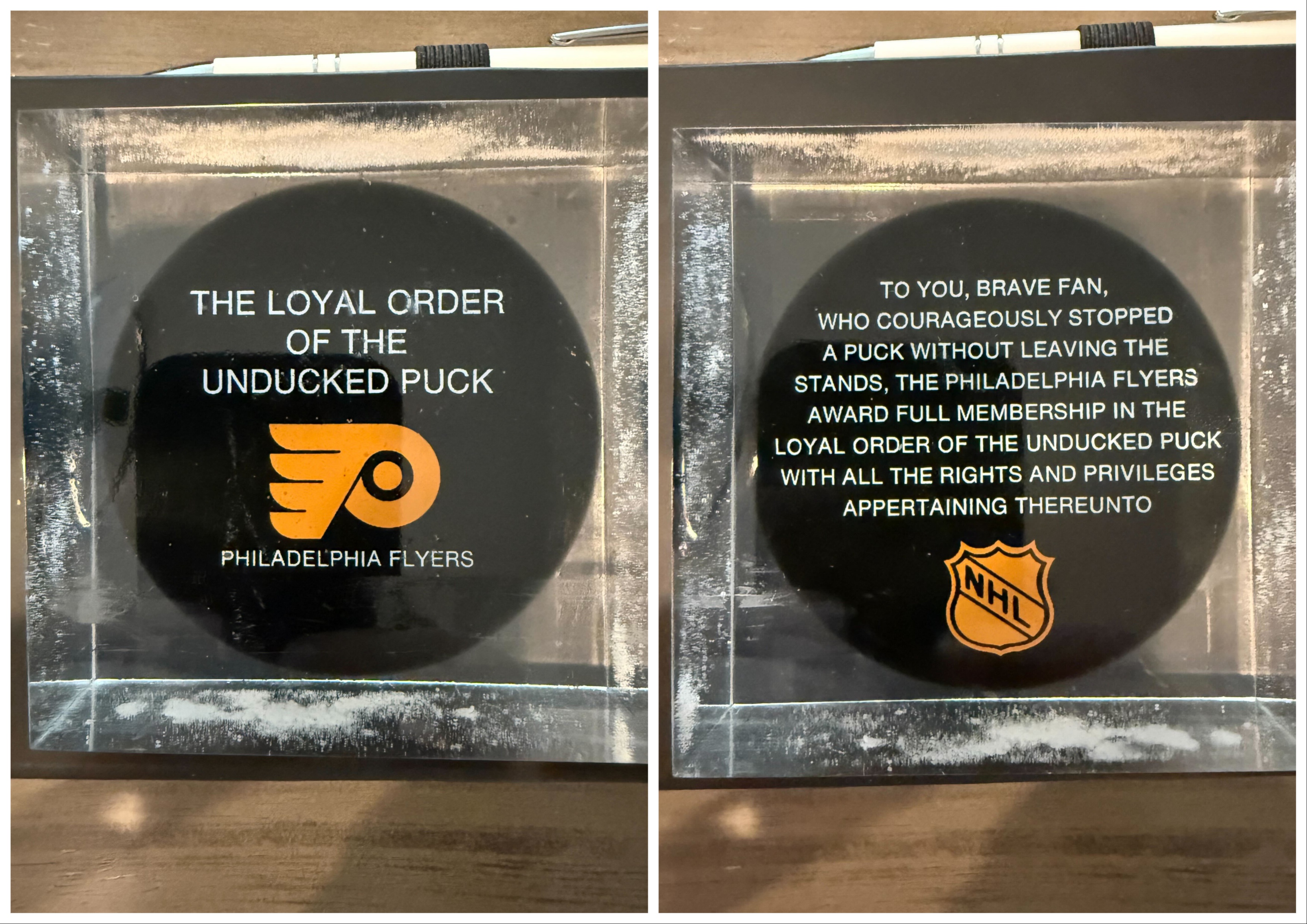

A package was shortly after delivered to her home in Bala Cynwyd. Fineberg was officially a member of the “Loyal Order of the Unducked Puck,” an exclusive club created by the Flyers in the 1970s partly as a way to dissuade fans from suing them if they were hit by a puck. You could not purchase a membership. You had to earn it.

“It was screaming,” her son said of the puck. “I’m amazed it didn’t break her jaw.”

A negative to a positive

A fan wrote to the Flyers in the early 1970s, letting them know that she was hit by a puck at the Spectrum and her outfit was ruined. Lou Scheinfeld, then the team’s vice president, told the fan the team would replace the bloodied clothes and get her tickets to a game. But he wanted to do more.

Ronnie Rutenberg, the team’s lawyer, envisioned more fans complaining about being hit by pucks and feared that lawsuits would be filed. The Flyers, he said, needed to turn being hit by a puck into a positive.

“He figured that if we made people feel special, they wouldn’t sue us,” said Andy Abramson, who started working at the Spectrum in the 1970s and became a Flyers executive in the 1980s. “Ronnie was brilliant.”

So the Flyers created the Loyal Order of the Unducked Puck and made fans feel brave for having been hit by an errant shot. Scheinfeld advised security members to immediately attend to any fan who was struck, bring them to a first-aid station, and gather their information.

The team then sent them a letter signed by a player and a puck with an inscription written by Scheinfeld printed on the back.

“To you brave fan who courageously stopped a puck without leaving the stands,” the inscription read. “The Philadelphia Flyers award full membership in the Loyal Order of the Unducked Puck with all the rights and privileges appertaining thereunto.”

The pucks were sent to fans for years, easing the pain of being hit by a frozen piece of rubber and making a bruise feel like an initiation. In 2002, the NHL mandated teams to install protective netting behind each goal after a 13-year-old girl was killed by a puck that was deflected into the stands. The netting has stopped most pucks from entering the stands, all but eliminating the need for a Loyal Order.

“You couldn’t buy your way in,” Abramson said. “You had to live through the experience in order to qualify. And you had to be willing to give up your personal information to a representative of the Spectrum in order to be enrolled.

“Let’s say you got hit and shook it off. We never knew, and you didn’t get in. It’s one of these unique things that made the Flyers who we were. It wasn’t just a hockey team.”

The perfect arena

The rows of seats inside the Spectrum were steep, because the arena was built on just 4½ acres, forcing developers to build up instead of out. It was perfect for hockey.

“Every seat was close to the ice, and you were on top of the action no matter where you were,” Scheinfeld said. “The sound was deafening. You could hear the click of the stick when the puck hit it. When a guy pulled up in front of the goalie and his skate sent an ice spray, you could hear that.

“It was like a Super Bowl every game. You couldn’t get a ticket. People didn’t give away their tickets to a friend or company. They came.”

And the pucks came in hot.

“We were right in the shooting gallery,” said Toni-Jean Friedman, whose parents had season tickets behind the net. “Thinking about that now, that was really crazy.”

Friedman’s mother was introduced to hockey in the 1970s, falling for the foreign sport at the same time nearly everyone else did in the region. Fran Lisa and husband Frank met a couple of friends at Rexy’s, the haunt on the Black Horse Pike where the Broad Street Bullies were regulars.

The Lisas met the players, got Bobby Clarke’s autograph on the back of a Rexy’s coaster, and bought season tickets at the Spectrum. A few years later, a puck was headed their way.

“She was trying to catch it, but then survival instincts took over,” Friedman said. “We saw people taken out in stretchers.”

The puck hit Lisa’s wrist and ushers rushed to her seat. She shrugged it off and watched the game. They jotted down her address in Marlton Lakes, and a puck was soon on its way. She was a member of the Loyal Order.

“She was proud of it. She showed it to everyone,” her daughter said. “So it worked because she would’ve never thought twice about suing, not that that’s who she was anyway.”

The Flyers had Clarkie, Bernie, The Hound, and The Hammer, but the Spectrum was more than just the Bullies. Sign Man was prepared for anything, Kate Smith brought good luck, and a loyal order of fans sold out every game. Hockey in South Philly — a foreign concept years earlier — became an event.

“There was always action. There was always something going on,” Fineberg said. “And you never thought the Flyers were going to lose. I remember going into the third period and they’re down, and Bobby Clarke … it gives me chills … Bobby Clarke just took over and would score and bring them back. It gives me chills thinking about it. It was unbelievable.”

Fineberg bought season tickets in the late 1960s for $4.50 a seat as a teenager attending the Haverford School. His mom started going with him a few years later, knitting in the stands and wearing sandals no matter how cold it was outside.

“I can still see her crossing Pattison Avenue in the snow with sandals and no socks,” said her daughter, Betsy Hershberg.

The faces in the crowd became almost like family as they invited each other to weddings and kept up with more than just hockey. A couple from Delaware sat next to the Finebergs, a UPS driver was in front, a teenager from Northeast Philly was down the row, the Flyers’ wives were nearby, and Charlie was in Seat 1.

“Charlie had one of those comb overs. He was an older guy,” Fineberg said. “I remember one time, the Flyers scored and everybody jumped up. A guy in the back spilled his beer on Charlie’s head and his hair was hanging down to his back.

“You go to all these games with these people and share all these experiences. You can’t help but have a bond with them.”

A lasting legacy

Nancy Fineberg is 99 years old and watches sports on TV. Her 100th birthday is in March. She went to Methodist Hospital after the Flyers won that game and left with 25 stitches. A faint scar is still visible on her chin. Her grandson Dan Hershberg has the puck the Flyers sent to her house, clinging to the symbol of his grandmother’s induction into the Loyal Order like it’s a family heirloom.

“My grandmom is kind of like an old-school badass,” Hershberg said. “Yeah, I was at the hockey game and things happen and you move on.”

The original Loyal Order puck was a cube of Lucite with a Styrofoam puck inside — “Seriously?,” Friedman said — because a real puck would be too heavy. The Flyers later created plaques for members. They also sent a letter signed by a player. Friedman’s mother heard from Bernie Parent.

Dear Fran,

Unfortunately, you are now a full-fledged member of the Loyal Order of the Unducked Puck. I know your initiation was tough, but now that you have passed it with flying colors, Pete Peeters, Rick St. Croix, and myself (all honorary members) would like to take this opportunity to welcome you to the club. Everyone in the Flyers organization hopes you are now feeling fine and we hope you’ll accept this little memento of your unpleasant experience with a smile.

Best regards,

Bernie Parent

Fran Lisa died in March. There was always a game on TV, her daughter said, and Lisa knew all the stats. When the family wrote her obituary, they mentioned how she “showered people with love and food” and invited everyone to her Shore house. Lisa, they said, was the axis of her family.

And they also made sure the obituary included that she was a member of the Loyal Order of the Unducked Puck. Lisa was 85 years old and being hit with a puck at the Spectrum was worth a mention. The family wanted all to know that their mother earned her place in the Loyal Order.

“It was her,” Friedman said. “To her, she felt like she was a Flyer because of this whole thing. She was in the club. I can’t describe it any other way but she was proud. It was a great idea.”