Mike Golic still remembers standing on the sideline when quarterback Randall Cunningham fell to the grass at Lambeau Field. It was Game 1 of the 1991 Eagles season. In the second quarter, Packers linebacker Bryce Paup lunged at Cunningham’s knees.

The trainers rushed to his side. Golic and his defensive teammates were stunned. This was supposed to be their year. Now, as Cunningham rolled on his back in agony, that seemed less likely.

With Cunningham out for the season, the Eagles cycled through a litany of quarterbacks in 1991. It gave the defense virtually no room for error — but instead of faltering, it rose to the occasion.

Over the next 16 games, the group put together one of the best defensive seasons in NFL history — if not the best — surrendering the fewest passing yards and rushing yards along with the lowest completion percentage in the NFL that season.

“I know that group all too well,” analyst Troy Aikman said on Monday Night Football on Dec. 8. “Because I played against them. Number one against the run. Number one against the pass. I could name the roster for you, on the defensive side of the ball.”

The 1991 Eagles recorded the most sacks in the league (55) and ranked third in interceptions (26). They allowed an average of 15.3 points per game.

“We knew that we were going to go as far as the defense could carry us,” linebacker Seth Joyner recalled in late November. “And that just turned the intensity up.”

The current Eagles defense is not in quite the same predicament. Their quarterback is healthy. Nevertheless, through 14 games, Jalen Hurts’ offense has not performed relative to its talent level.

And while the 2025 defense has not been as consistent as the 1991 group, it has shown flashes of the same caliber of dominance, particularly since the bye week.

If the Eagles have any hopes of returning to the Super Bowl, such a run would likely have to involve an elite defense. With that being said, here is what three members of Gang Green — Joyner, Golic, and Clyde Simmons — are seeing from Vic Fangio’s group.

Aggressiveness

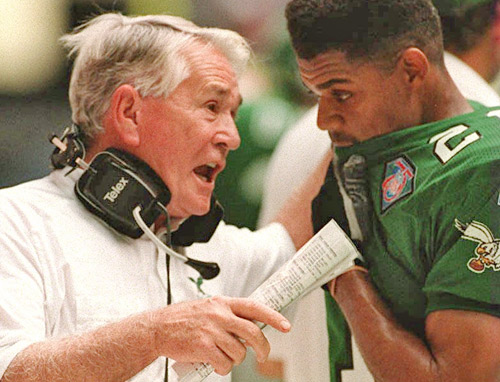

Buddy Ryan, the defensive guru who coached the Eagles from 1986-90, had a mantra: “Score on defense.”

This meant pitching the ball from player to player if you got an interception. Or, if you got a fumble, trying to scoop and score instead of falling on the ball. Or, if you didn’t score, giving the offense a shorter field.

Ryan’s philosophy wasn’t just about preventing a team from scoring; it was about putting that team’s offense on the defensive.

That carried over to the 1991 team, even after Ryan was fired following the 1990 season. The 1991 defense, coached by coordinator Bud Carson, brought this concept to a new level.

With Cunningham out, it was unlikely the Eagles would be scoring 20-30 points a game. So, the defensive players took it upon themselves to score — or, at a minimum, make things easier for the offense.

Golic, a former defensive tackle who now hosts a show on FanDuel Sports Network, said this message was largely player-driven. It was always reiterated, either on the sidelines or in defensive meetings.

“We played aggressively anyway, but we kind of even upped that,” Golic said in November. “And it wasn’t disparaging to the offense. It was just, like, ‘Listen, we don’t have our starting quarterback anymore. We know we do a lot on this team, but we know we now have to do more.’ So it was more of an up-tempo, upbeat, ‘Let’s do more. Let’s help out more.’”

Added Simmons, a dominant defensive end: ”We’d always prided ourselves with being a really good defense, but we knew we had to be even better to win ballgames. It started really getting tightened down. Just try to be sure to give ourselves all the opportunities in the world to win ballgames, keep people off the scoreboard, and keep the yardage down.”

Golic and Joyner see a similar aggression in the Eagles’ current group — both in the play-calling and in the players. This has been especially true with the addition of Jaelan Phillips, the return of Brandon Graham, and Nakobe Dean playing above expectations after returning from a serious knee injury.

It has freed up the pass rush, allowing Fangio to be more unpredictable — a Ryan/Carson staple. Fangio isn’t blitzing as much as those teams, but he is mixing in different looks. One example is that he favors a simulated pressure in which at least one linebacker rushes and one lineman drops into coverage.

“Bud Carson as the D coordinator, he was a very aggressive coordinator, and certainly Vic’s a very aggressive coordinator,” Golic said. “And players love playing aggressively. You’d rather be attacking than reacting. So that’s probably the biggest comparison.

“I mean, obviously I’m biased toward my 1991 team. The stats were ridiculous. But I would say overall, yeah, the aggressiveness of the two units would be comparable.”

He added: “A lot of it is just trusting the person next to you, behind you, in the secondary, and them trusting us up front that we’re going to get there. Players know when they’re going to be on an island and understand that and accept the responsibilities of it. And coaches like Fangio and Bud Carson certainly weren’t afraid to be aggressive and put people on islands.”

Players who would fit on Gang Green

There was only one player whose name came up repeatedly as example of someone who evoked the 1991 team — and it shouldn’t come as a surprise.

The family of Jerome Brown said in March that they see some of the late Eagles defensive tackle in current Eagles DT Jalen Carter, who has been sidelined the past two weeks with shoulder injuries. To the 1991 Eagles, the comparisons are obvious.

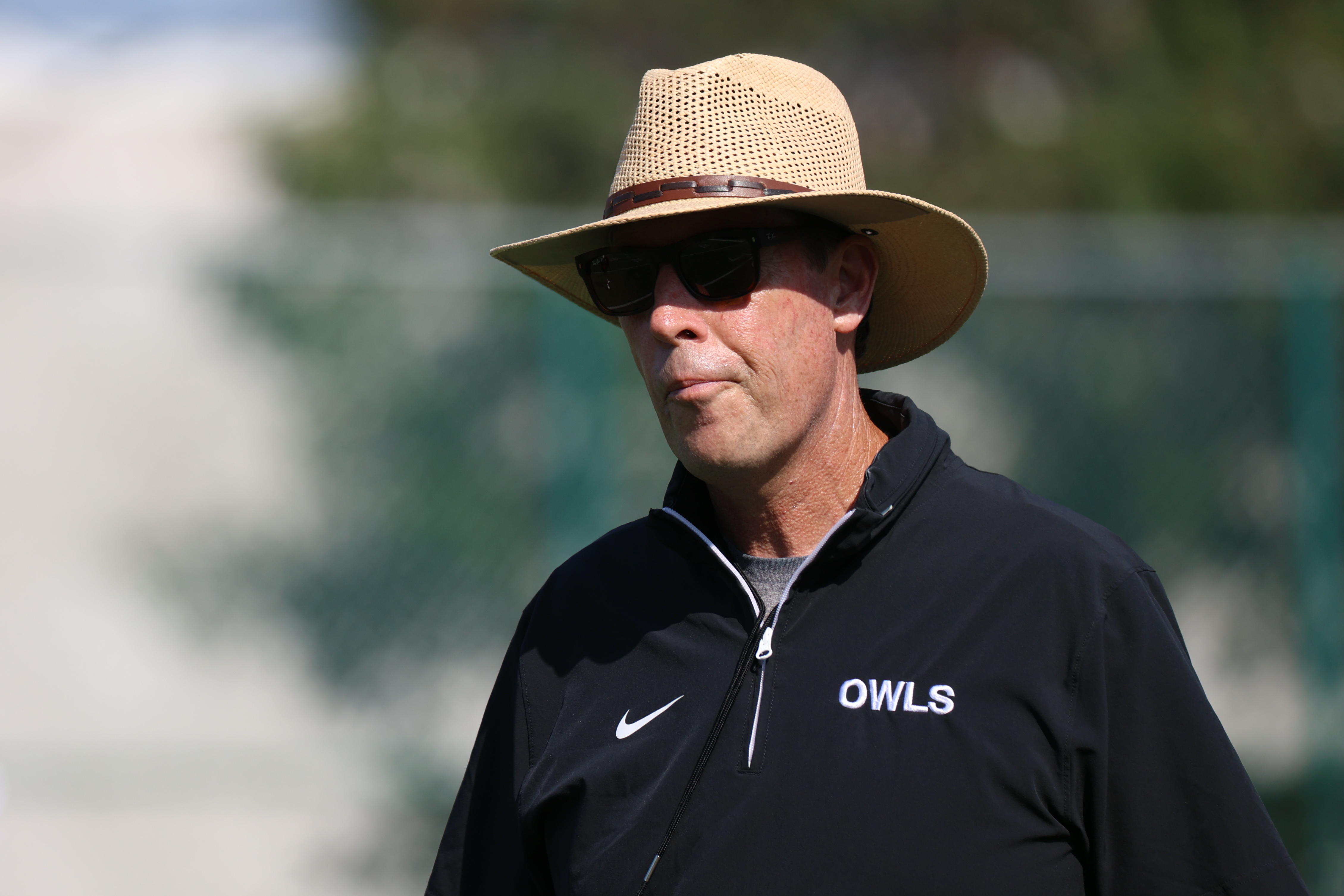

Simmons, the defensive line coach at Bowling Green, doesn’t have much time to keep tabs on the Eagles. But even in the limited games he has watched, Carter has stood out.

“I know they’ve got a couple good players in there, like a Jalen Carter, who is such a big man, and so explosive, and a game-controlling guy,” Simmons said last month. “He’s special. You don’t see a lot of people that big, who are that explosive.”

“He plays on the other side of the line [of scrimmage],” Golic added. “I mean, he just plays with leverage, with strength. You know, and the ends were bigger at that point. Reggie [White] was 315 pounds, Clyde was 290 pounds, Jerome was 300, I was in the 280s, 290, so was Mike Pitts.

“Jalen [Carter] is a 300-pounder who is quick off the ball and plays on the other side of the line. That’s what we always did. We always played on the other side of the line. And he would have, jeez … I mean, put him on that line, with Jerome [Brown] in the middle, would have been ridiculous.

“If there’s one player on that defense that would have fit in our defense, it definitely would have been Jalen [Carter].”

Joyner, a former linebacker who hosts pregame and postgame Eagles shows on YouTube, made a different comparison. In Phillips, he saw a bit of Simmons — a multifaceted player who could run different formations and be put in different spots.

“I probably would have to compare him to Clyde,” Joyner said of Phillips. “I definitely wouldn’t compare him to Reggie [White, a Hall of Famer] because there’s just no comparison to that guy. But I think when you when you think about Clyde, especially under Buddy … because under Buddy, we ran a little bit of everything. We ran 30 front and 40 front, unders, overs, swim package, with all three linebackers off the ball in an even front. We ran a little bit of everything.

“And in the 30 front, Clyde was pretty much the weakside outside linebacker. Like, we could line up in a four-man front, quarterback getting his cadence. We could shift to a 30 front, Clyde would kick his hand off the ground, and stand up as an outside linebacker. And sometimes even drop into coverage, believe it or not.

“Those are some of the intangibles that Jaelan Phillips brings to the table. Because like I said, I was shocked to see Vic actually drop him off in coverage out of that five-man front [against the Lions]. And in some of the zone blitzes where you brought a linebacker from the other side and you dropped him off into the flat. He brings a versatility.”

A Super Bowl-caliber defense

All three former players looked at the 1991 season as a lost opportunity. They believe that if Cunningham had stayed healthy, they could have won a Super Bowl.

Instead, the 1991 Eagles went 10-6 and didn’t make the playoffs. But these Eagles are in a different spot, which leads Simmons, Joyner, and Golic to believe the outcome could be better for them.

Joyner sees the same confidence in the 2025 group that the 1991 group had. Golic sees it, too.

Now, it’s a matter of play-calling and playing with the same confidence on the offensive side of the ball.

“It’s definitely possible [for them to go back-to-back],” Golic said. “Listen, the offense, it’s tough to duplicate. The [offensive] line has not been what it was last year. They still run more than they pass. They still try and live off the run. But you can never negate a great defense. What a great defense will do will always keep you in the game, always.

“So you look at some of the top defenses, like Denver, like Houston, Philly, certainly is one of them, you’re always going to be in the game. And then you just need the offense to produce some. And certainly the Eagles offense has the ability to [do that].

“Statistically, they’re not what they were last year, but they have the ability to show it. But when you have a really good defense, you’re going to be in every game.”