One man, buried under $20,000 in online gambling debt, became homeless. A woman lost $13,000 and missed her last five mortgage payments. A mother gambled away her son’s college tuition, piling up over $100,000 in debt.

Such dire stories — shared with gambling helplines in Pennsylvania and New Jersey in recent years — are on the rise. And for the growing number of people, the problem isn’t the casino, but the apps on their phones that let them gamble anywhere, 24-7.

“My family is hosting fundraisers for my son who had a stroke, and here I am, gambling on my phone,” one caller said. “What’s wrong with me?”

The Philadelphia media market — which encompasses the city, Southeastern Pennsylvania, and central and southern New Jersey — has become an epicenter of online gambling in the United States. In 2024, internet gaming and sports wagering revenues alone topped $6 billion in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, up from about $3.6 billion in 2021.

In the same period, the number of calls and texts to 1-800-GAMBLER rose in both Pennsylvania and New Jersey, two of only six states in the U.S. where both sports betting and online casino games are legal. But calls about online gambling problems rose significantly more — 180% in Pennsylvania and 160% in New Jersey in that period. In 2019, only about one in 10 Pennsylvania callers said online gambling was the main issue. By 2024, it was every other caller.

window.addEventListener(“message”,function(a){if(void 0!==a.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var e=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var t in a.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r,i=0;r=e[i];i++)if(r.contentWindow===a.source){var d=a.data[“datawrapper-height”][t]+”px”;r.style.height=d}}});

The Inquirer analyzed anonymized helpline call logs, state revenue reports, and advertising data to shed light on how the Philadelphia-area market has become a hub for the online gambling industry. An increasing volume of gamblers face financial devastation as they struggle to get off the apps.

As of this fall, the Philadelphia media market outpaced New York City and Las Vegas as the No. 1 market for internet gambling advertisement, with companies spending more than $37 million on ads between January and September, according to data provided by Nielsen Ad Intel.

As many as 30% of Pennsylvania adults now gamble on online sports with some regularity, according to researchers at Pennsylvania State University who conduct an annual, state-funded survey of online gambling. And as many as 6% of Pennsylvanians, or 785,000 people, are estimated to be problem gamblers, according to the most recent survey, which is not yet published.

While problem gambling has a range of severity, the American Psychiatric Association recognizes it as a mental health condition. A gambling disorder is defined by a persistent pattern of problematic betting with an inability to limit or stop, leading to emotional, financial, and or relational distress.

For many, the losses are crushing. In New Jersey, helpline callers reported a combined $28 million in debt at least among people who disclosed this financial information, averaging about $34,000 for each of these callers. In Pennsylvania, 60% of those people willing to share said they owed money, though the state does not track totals.

Across both states, callers reported they had drained entire retirement accounts, lost homes to bank foreclosure, or blown through entire paychecks. One anonymous caller in New Jersey reported losing $400,000 in a single night — his life savings.

“We [also] have people who call us and say, ‘I think I’m doing this too much. I think I need a little bit of help,’” said Josh Ercole, executive director of the Council on Compulsive Gambling of Pennsylvania, the state-funded nonprofit that runs the hotline for the commonwealth’s residents.

Four calls made in New Jersey between 2023 and 2024 were about children under the age of 12 struggling with gambling problems, according to the state’s fiscal year report. Ten other calls were about children under the age of 18. In Pennsylvania, 10 calls involved children between the ages of 13 and 17.

Experts say the explosion of sports betting and casino apps has fueled what is increasingly seen as a public health crisis, as gambling profits and state tax revenues derived from them have soared since sports betting’s legalization in 2018. And Philadelphia is now viewed as something of a promised land for e-gambling boosters.

window.addEventListener(“message”,function(a){if(void 0!==a.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var e=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var t in a.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r,i=0;r=e[i];i++)if(r.contentWindow===a.source){var d=a.data[“datawrapper-height”][t]+”px”;r.style.height=d}}});

Uttara Madurai Ananthakrishnan, an economics professor at the University of Washington who has studied the psychology of gambling, said lawmakers have struggled to keep pace with the industry’s meteoric growth.

“I don’t think people expected it to explode at this level,” said Madurai Ananthakrishnan, who previously worked in Pennsylvania. “All of this is going to slowly add up and cause a ton of issues downstream.”

Harrisburg also benefited handsomely from the high rollers, drawing $165 million last year in gambling taxes, up from $46 million five years prior. About $10 million was earmarked for gambling addiction helplines and treatment programs, which came directly from industry profits.

Online betting now accounts for nearly half of all gambling revenue in Pennsylvania, according to an Inquirer analysis of state reports. Pennsylvanians wagered a staggering $8.3 billion during the 2024-25 fiscal year in online sports betting alone, making it by far the most popular gambling method. Total revenue for sportsbook and iGaming sites rose past $2.9 billion last year.

window.addEventListener(“message”,function(a){if(void 0!==a.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var e=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var t in a.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r,i=0;r=e[i];i++)if(r.contentWindow===a.source){var d=a.data[“datawrapper-height”][t]+”px”;r.style.height=d}}});

In New Jersey gaming revenue was nearly $6.3 billion in 2024 — $3.3 billion of which came from internet gaming and sports wagering, according to the state’s Casino Control Commission’s annual report.

Yet the amount spent online is almost certainly higher than what states can track — as is the number of people who have developed online problems.

Caron Treatment Center, a Pennsylvania-based substance use treatment facility, said 160 people in their inpatient treatment problem were struggling with gambling this year — a 162% increase from five years ago.

“I’ve been getting call after call about gambling,” said Eric Webber, a behavioral health specialist and gambling counselor at Caron. “It’s a national crisis that doesn’t have a national solution.”

Fewer than two dozen gambling sites are technically legal in Pennsylvania. But thanks to pervasive online advertising, many gamblers now use so-called offshore gambling sites that are not regulated by the state.

As of last year, more than 20% of online gamblers were using these illegal or unregulated sites, according to the 2024 Penn State report. Such sites often lack state-mandated guardrails like easily allowing users to set weekly betting limits or request a “self-exclusion” — a voluntary ban from licensed casinos, internet-based gambling, video gaming terminals, and fantasy sports wagering.

Self-exclusions in Pennsylvania are higher this year than last year — 8,315 people have already opted out compared with the 7,489 people who requested a ban through Dec. 31 of last year.

Major online sportsbooks say they are going above and beyond.

Beyond self-imposed spending limits, FanDuel, one of the largest sports betting advertisers in the Philadelphia market, introduced a dashboard to allow gamblers to track their spending habits. The company also began tracking betting patterns on its platform and alerting customers when they bet more than their normal wager.

“When users attempt to deposit significantly more than their predicted amount, we surface that information to them and prompt them to reduce their deposit or to set a go-forward deposit limit,” a FanDuel spokesperson said.

DraftKings, in a statement, said it works closely with a gambling company alliance to support responsible betting, “leveraging technology to help detect signs of potentially problematic behavior.”

Some lawmakers want to see more regulation. State Rep. Tarik Khan, a Democrat who represents parts of Montgomery County and Philadelphia, has called for hearings to examine best practices to rein in an industry that he said heavily targets youth.

“More and more people, especially young people, are getting addicted to it, and blowing large portions of their paychecks on feeding this addiction,” Khan said. “It’s already pervasive, and it’s going to get worse.”

‘I’ve gambled everything away on FanDuel’

In New Jersey, more than half of the callers to gambling hotlines who disclosed their age were under 35. In Pennsylvania, people under 35 accounted for 41% of callers.

“Things have shifted to a younger crowd,” said Ercole, of the Council on Compulsive Gambling of Pennsylvania. “Typically our highest call volume used to be in the 35 to 55 ranges.”

People from all professions are affected — nurses, construction workers, software engineers, chefs, attorneys, postal workers, microbiologists, and tattoo artists. Some are students, retirees, or unemployed.

Regardless of one’s income level, online gambling can put serious strain on personal and professional lives. Some people told of losing contact with their parents, getting divorced, or being cut off from friends.

Others lost jobs or had their homes and cars repossessed.

“I have nothing,” a 30-year-old caller told a New Jersey helpline operator in 2023. “I’ve gambled everything away on FanDuel.”

Most people are calling about their own gambling problems. But dozens of family members called to ask for help with their loved ones’ betting. In one case, a woman asked if she could use her father’s Social Security number to ban him from online betting apps.

Many gamblers do not call the hotlines or seek professional help until they face financial ruin or they are confronted by family members.

At the height of his problem, one man from New Jersey started gambling on Russian table tennis matches and Australian basketball games. His wife, who spoke to The Inquirer on condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive family matter, said his compulsion had grown so severe that he needed a fix to hold him over between sports seasons.

“He was betting $1,000 on a sport he knows nothing about, played by people he’s never heard of before,” his wife said.

The husband kept his gambling hidden for her years, until she found his secret bank account — along with two dozen maxed-out credit cards and records of tribal loans he had taken out, one of them with a 300% interest rate. She also learned that, in 2021, he had quietly lost $70,000 while the newlyweds were on their honeymoon in France.

“It’s horrifying,” she said.

The casino-to-app pipeline

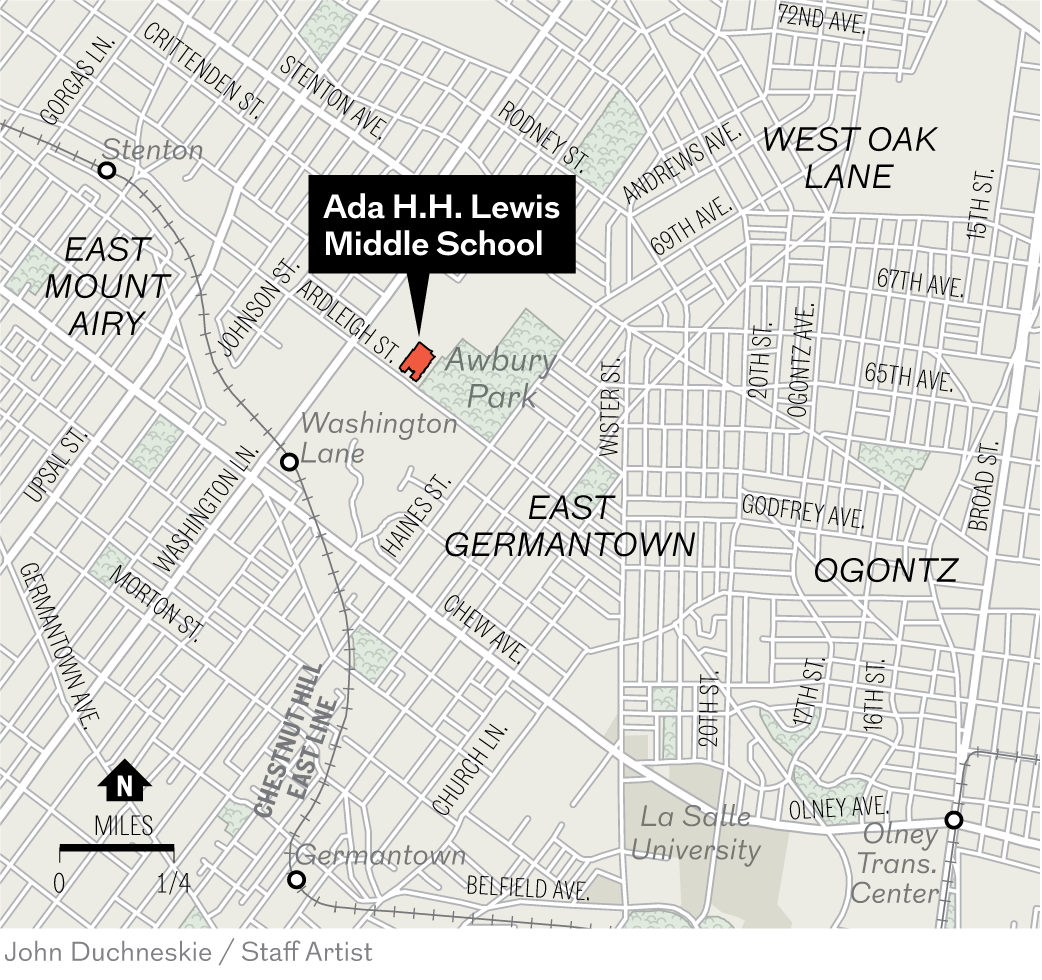

Across Pennsylvania, as of 2024, people sought help for addiction to internet games more than any other type of gambling, especially in the suburbs.

In Montgomery County, the most common type of gambling problem cited was internet slots — with 47 calls. In Bucks, internet sports had the highest volume with 34 calls.

In Philadelphia, home to both Live! Casino and Rivers Casino, in-person games remain the largest reported problem for struggling gamblers, according to call center logs.

Some brick-and-mortar casinos, however, have seen business drop as bettors migrate to their phones. At Rivers Casino Philadelphia, sports-betting revenue fell from $29 million in fiscal 2019 — the first full year of legal wagering — to $11 million in 2024, according to state records.

But even in Philadelphia, a county with two casinos, the number of calls and texts for online gambling shot up in recent years. And experts say that people who gamble exclusively online show heightened risk.

“You can get cut off at the casino. You could walk away from the machine,” said Gillian Russell, an assistant Penn State professor who works on the annual online gambling survey. “Those things that maybe cause breaks, a lot of those things are removed.”

About 13% of people who gamble both online and in person were classified as problem or pathological gamblers, according to the 2024 Penn State survey. Online-only gamblers, though just 3% of the total gambling population, showed even greater risk: 37% fell into problem categories.

Prop bets, the practice of betting on various occurrences within a game rather than just the outcome, are a pointed concern. Such wagers have come under scrutiny as bet-fixing schemes ensnare athletes from the NBA, MLB, the NCAA, and even niche sports like table tennis.

Among normal gamblers, however, prop bettors are far more likely to develop problems, Russell said. Webber, the gambling counselor, likened in-game prop betting to a constant stream of small dopamine hits, which create a kind of withdrawal.

And with gambling sites offering bonus cash and rewards points, he said, the temptation can feel constant.

“DraftKings says, ‘Hey, I haven’t seen you in a couple weeks, here’s $50.’ The local beer distributor doesn’t say, ‘Hey, you haven’t been here in a while, here’s a cold six-pack,’” he said. “That doesn’t help somebody who’s struggling.”