In the wake of the U.S. Bicentennial, in which Philadelphia was at the center of a yearlong celebration of the country’s 200th birthday, one of the city’s contributions to public health was put on the chopping block.

On Feb. 15, 1977, city officials confirmed that Mayor Frank Rizzo was closing Philadelphia General Hospital.

The poorhouse

Philadelphia General Hospital traced its lineage back to 1729, predating even the revered Pennsylvania Hospital, which was founded in 1751 and is generally considered the nation’s first chartered hospital.

Philadelphia General Hospital was originally established at 10th and Spruce Streets as an almshouse, also known as an English poorhouse.

“The institution reflected the idea that communities assume some responsibility for those unable to do so themselves,” Jean Whelan, former president of the American Association for the History of Nursing, wrote in 2014.

The almshouse was used as housing for the poor and elderly, as well as a workhouse. It also provided some psychiatric and medical care.

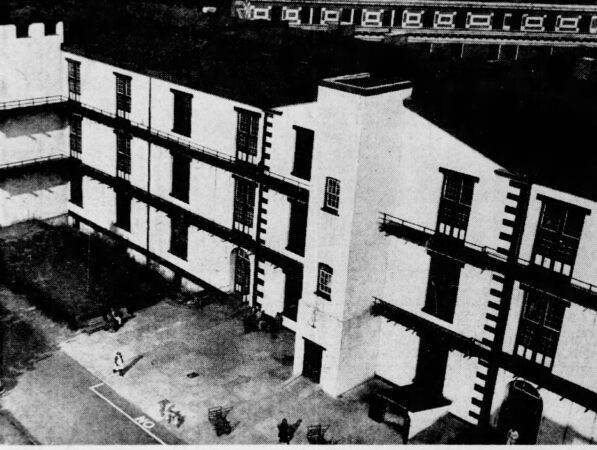

It moved in the mid-1800s into what was then Blockley Township, at what is now 34th Street and Civic Center Boulevard, and began offering more traditional medical services. The Blockley Almshouse’s barrage of patients and their variety of maladies helped it naturally grow into a teaching tool for nursing and medical students.

And by turn of the 20th century, it had become a full-blown medical center, made official by its new name: Philadelphia General Hospital.

But it held onto its spirit.

Its doors were open to anyone who needed care, no matter that person’s race, ethnicity, class, or income.

Healthcare was a given. Workers saw it as a responsibility.

Even if it wasn’t always the best care.

Poor health

The hospital relied on tax dollars, and as a result was often short on staffing and low on supplies. It was a source of political corruption, scandal, and discord among its melting pot of patients.

Eventually, it collapsed under the weight of its mission.

Its facilities became outdated, its services could not keep up, and its role as educator was outsourced to colleges and universities.

Philadelphia General Hospital’s closure left a gaping hole in available services in West Philadelphia. It was no longer there to help support the uninsured.

Before it officially closed in June 1977, it was considered the oldest tax-supported municipal hospital in the United States.

“There’s a common misunderstanding that PGH recently has become a poor people’s hospital,” said Lewis Polk, acting city health commissioner, in 1977. “It’s always been a poor people’s hospital. The wealthy never chose to go there.”

Its old grounds are now occupied by several top-rated facilities, including Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania medical campus.

A historical marker there notes Philadelphia General Hospital’s nearly 250 years of service to the community.