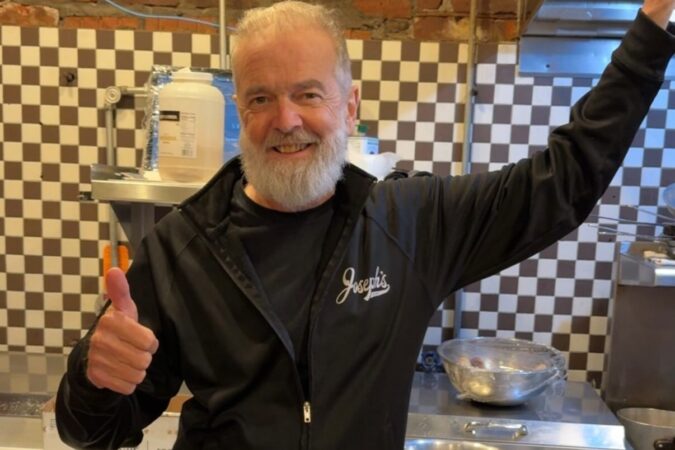

In his prime, Steve Sillman worked nights, Thursday through Monday.

And he was usually late coming in, despite only a 10-minute walk separating the front door of his impeccably preserved Fox Chase twin and the double red doors of Joseph’s Pizza Parlor.

The dayside managers would be tapping the toes of their dark work shoes, and Mr. Sillman would just glide in. He’d start turning radio dials in search of disco hits or a 1970s station, resetting the vibe with work-appropriate dancing to classic hits from Carole King and James Taylor. He’d remind anyone listening that he wanted disco played at his funeral.

And at the end of the night, hours after the other staff members had gone home, he’d pour himself a glass of red wine and close out the register, and then he’d call a few of the staffers and leave a message. He’d tell them to call back: “It’s important.” And when they called back, he’d say they missed a spot sweeping.

“You work with people so long,” said current Joseph’s co-owner Matt Yeck, “that you become like family.”

For the better part of four decades, and until the 70-year-old received a terminal brain cancer diagnosis earlier this year, Mr. Sillman was the face of the neighborhood’s trademark pizza place.

He started working there shortly after graduating from Northeast High School in the 1970s, and floated among the pizza parlor, neighboring Italian restaurant Moonstruck, and the once-wild Ciao nightclub above it.

He’d often speak of waiting on entertainment icon Elizabeth Taylor. (He would say he got lost in her transfixing blue eyes.) Over the course of those 40ish years, he became intimately familiar with the building’s quirks, and attended to its every need, from fixing broken faucets to decorating it for Christmas.

At the front of the house, he was the manager who would chat up customers before their order was ready. They always remembered his name, and sometimes he’d have to pretend to know theirs. In the back of the house, he was a peacekeeper, confidant, psychiatrist, dance partner, friend, and brother.

It was Mr. Sillman who raised an entire generation of neighborhood kids who came to Joseph’s for work. He watched them grow up, and then he folded them into his restaurant family.

He met his best friend of 40 years, Jane Readinger, through her siblings. They worked with Mr. Sillman at the restaurant, and over the years they folded him into their wider familial unit.

“A lot of his friendships came through that building,” said Jane, who is eight years younger. “And he had those friendships for life.”

It started with “P.L.P.’s,” or parking lot parties, after Joseph’s closed for the night. It grew into group ski trips and shared shore houses.

As his friends started getting married and having kids and growing up, Mr. Sillman, a lifelong bachelor, bought a Sea Isle house so they all had a place to stay.

But it was the twin on the corner of Jeanes Street and Solly Avenue that was his legacy. His grandparents built the house in 1914, and only his family — three generations — had called it home. He maintained its original layout and finishes and flourishes from the turn of the 20th century.

The home was a marvel at Christmas, as Mr. Sillman would decorate his and the adjoining twin together. Draping them in handmade ribbons, and bestowing showstopper wreaths made of fresh fruit.

After he was diagnosed in the spring with glioblastoma, members of that restaurant family would stop and see him on Jeanes Street, even as Mr. Sillman could no longer climb the three flights of stairs, and after he transitioned from the recliner to a bed setup in the dining room.

Even the new owners came. Yeck and his partner, Jimmy Lyons, awkwardly inherited Mr. Sillman when they bought Joseph’s in 2021. But it didn’t take long for both to see his indistillable value.

“Steve came with the building,” Yeck said.

As Mr. Sillman took his last breaths on the morning of Sunday, Nov. 23, with Jane cradling his head in her arms, Carole King’s 1971 classic played through the house: “You’ve Got a Friend.”

The outpouring of support in person and on social media was a nice reminder to Jane that people don’t need to be blood to be family. There’s family you’re born with, and then there’s family you collect along the way.

“He was never alone during this fight,” Jane said. As a registered nurse, she volunteered to help attend to Mr. Sillman as he entered hospice care at home.

Mr. Sillman is survived by his sister-in-law, Harriet Sillman; nieces and nephews; great nieces and nephews; and generations of former co-workers. His neighbors are planning to decorate the twin Jeanes Street houses in his absence this holiday season.

Services for Mr. Sillman will be held Saturday, Nov. 29, at the Wetzel and Son Funeral Home, 419 Huntingdon Pike in Rockledge. The viewing will be held from 8 to 10 a.m., followed by a funeral ceremony.

And then his extended family will honor Mr. Sillman’s wishes with an appropriate send-off: They’re throwing a disco party.

Donations in his name may be made to the American Cancer Society, Box 970, Fort Washington, Pa. 19034, or to the Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, 333 E. Lancaster Ave., Suite 414, Wynnewood, Pa. 19096.