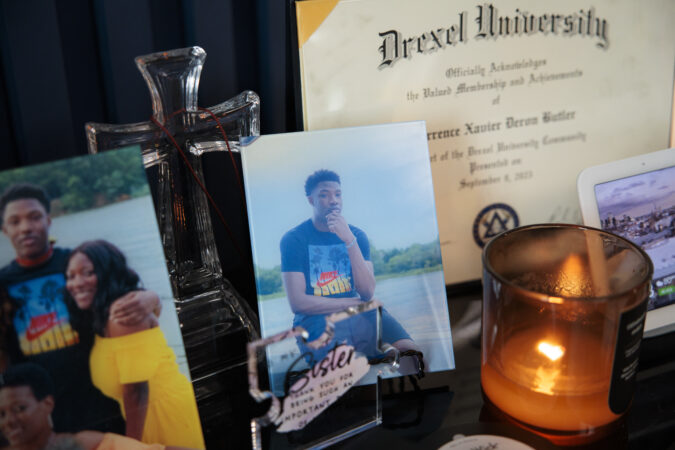

BRANDYWINE, Md. — No one knows exactly when Terrence Butler began keeping a journal, but there is a best guess. The first and only time someone noticed that he was writing something that he clearly wanted to keep private was the evening of Saturday, July 29, 2023, four days before he died.

He had spent that morning and afternoon at his mother’s townhouse here, curling and bending his 6-foot-7 body to lounge on the couch, cozy in a hoodie, gym shorts, and white socks, quiet, sometimes reading his Bible. His behavior was nothing out of the ordinary for whenever he was in town, though there was something about her son’s visit, this particular visit, that Dena Butler thought strange. Throughout Terrence’s two years at Drexel University, before and after he had stopped playing for the men’s basketball team, he merely had to call Dena whenever he had wanted to come home, and she would drive the 150 miles north to West Philadelphia to pick him up. This time, though, he had taken an Amtrak train from 30th Street Station, arriving in New Carrollton, Md., at close to 11 o’clock Friday night. He had never done that before.

His older sister Tiara was with him all day at Dena’s, happy to dote on her little brother, helping Dena prepare his favorite meals — bacon and eggs for breakfast; chicken fingers with his favorite condiment, Sweet Baby Ray’s barbecue sauce, for lunch — the two of them good-naturedly complaining that the Jamie Foxx movie they were watching was too slow and not all that funny.

It started to rain in the afternoon, and Terrence walked over to the wide window at the front of the house. He stood there for a while, leaning back a bit, his eyes turned to the charcoal clouds outside. Tiara remembers that moment still. “He loved the rain,” she said. “It wasn’t odd for him to do, but now, looking back on it, he was very somber, looking into the sky.”

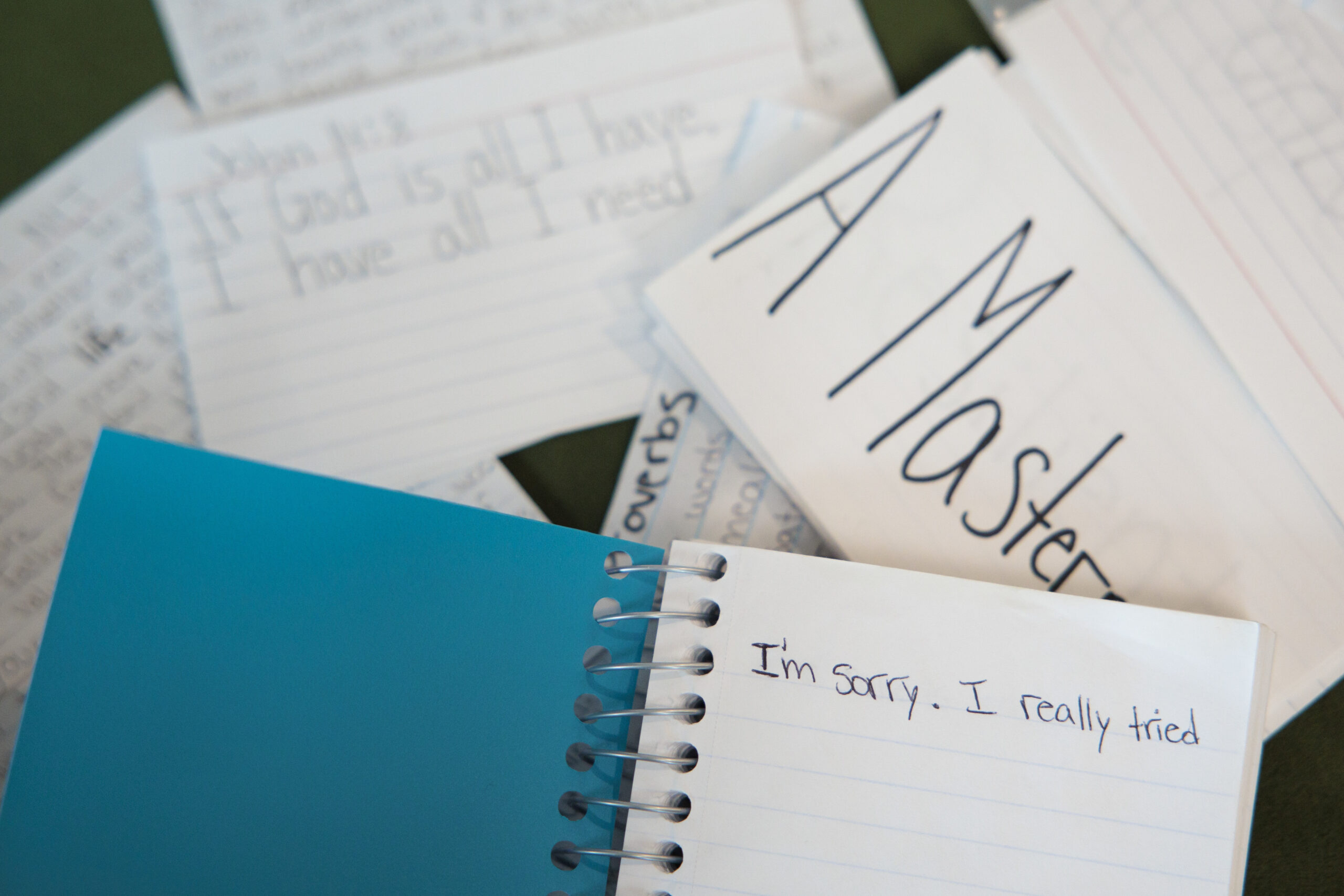

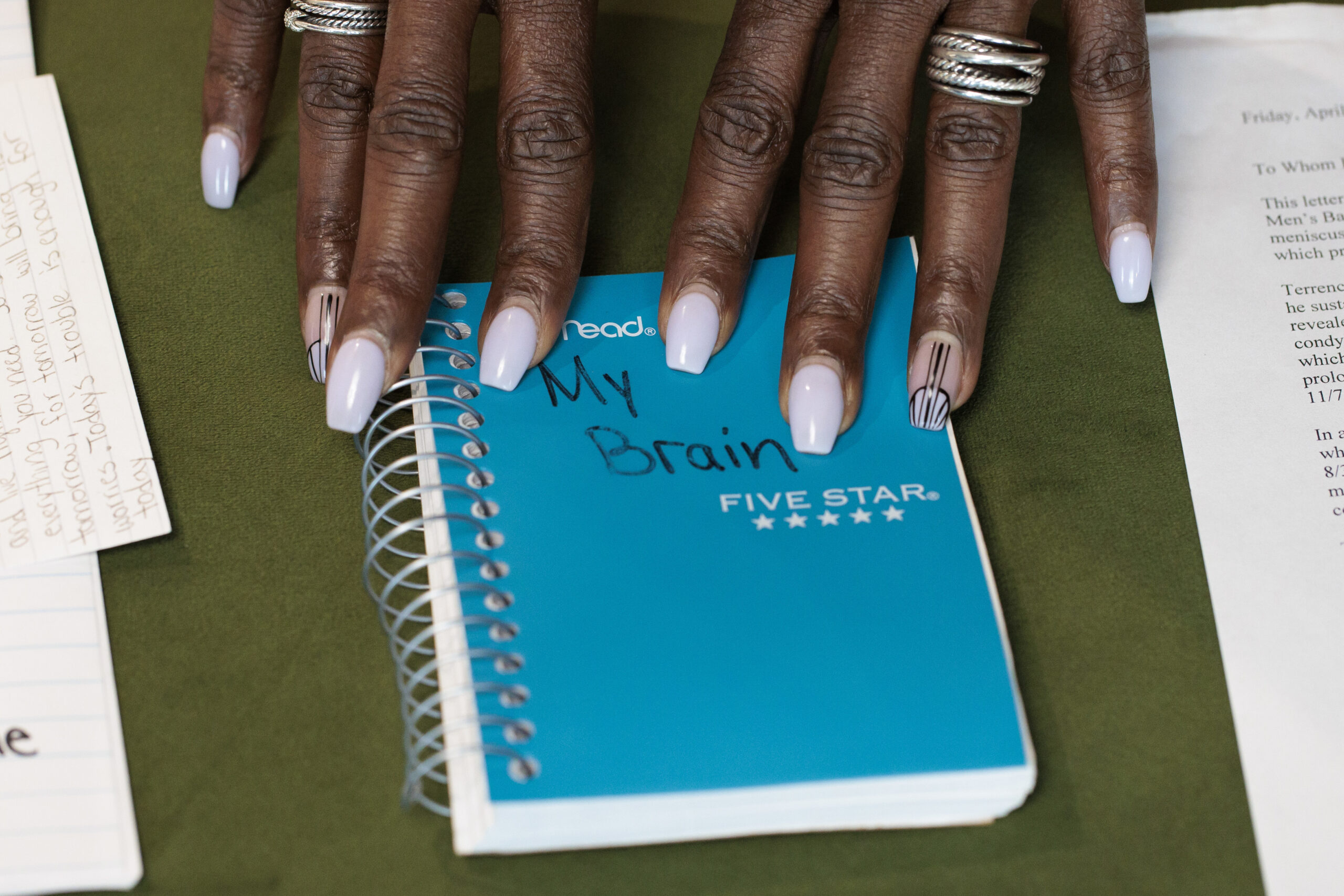

She drove Terrence back to their house; he would stay there that night, with Tiara and her husband, Arthur Goforth, to wake up for a 6:32 train back to Philadelphia the next morning. Before he went to bed, he sat on a barstool at Tiara and Arthur’s island, the farthest seat in their kitchen from their living room. In his hands were a black-ink pen and a notebook with a sky-blue cover.

Tiara assumed that he was finishing up some schoolwork. “After I got a little closer, he slowed down with the writing,” she said. “When I was further away, he was hunched over, writing.” She didn’t think anything of it until Wednesday, Aug. 2, when she and her family were combing through Apartment 208 of The Summit at University City, Terrence’s apartment, desperate for any clue that might tell them why he had shot himself.

The story of a young life

Twelve photographs on a wall in Zach Spiker’s office at Drexel tell the story of his decade as the university’s men’s basketball coach. There was Matey Juric, the 5-11 backup guard who was an “empty-chair kid” when Spiker recruited him: “I went to watch him play, and there were four chairs for college coaches, and they were all empty.” He’s in medical school now. There were team photos from the Dragons’ recent trips to Australia and Italy, from their celebration of their 2021 Colonial Athletic Conference Tournament championship. And there — in the picture from Italy, blending in among his friends and teammates — was Terrence Butler. It’s the only photo on the wall that Spiker took himself.

“It’s there for a reason,” he said, “and it will be as long as I’m here.”

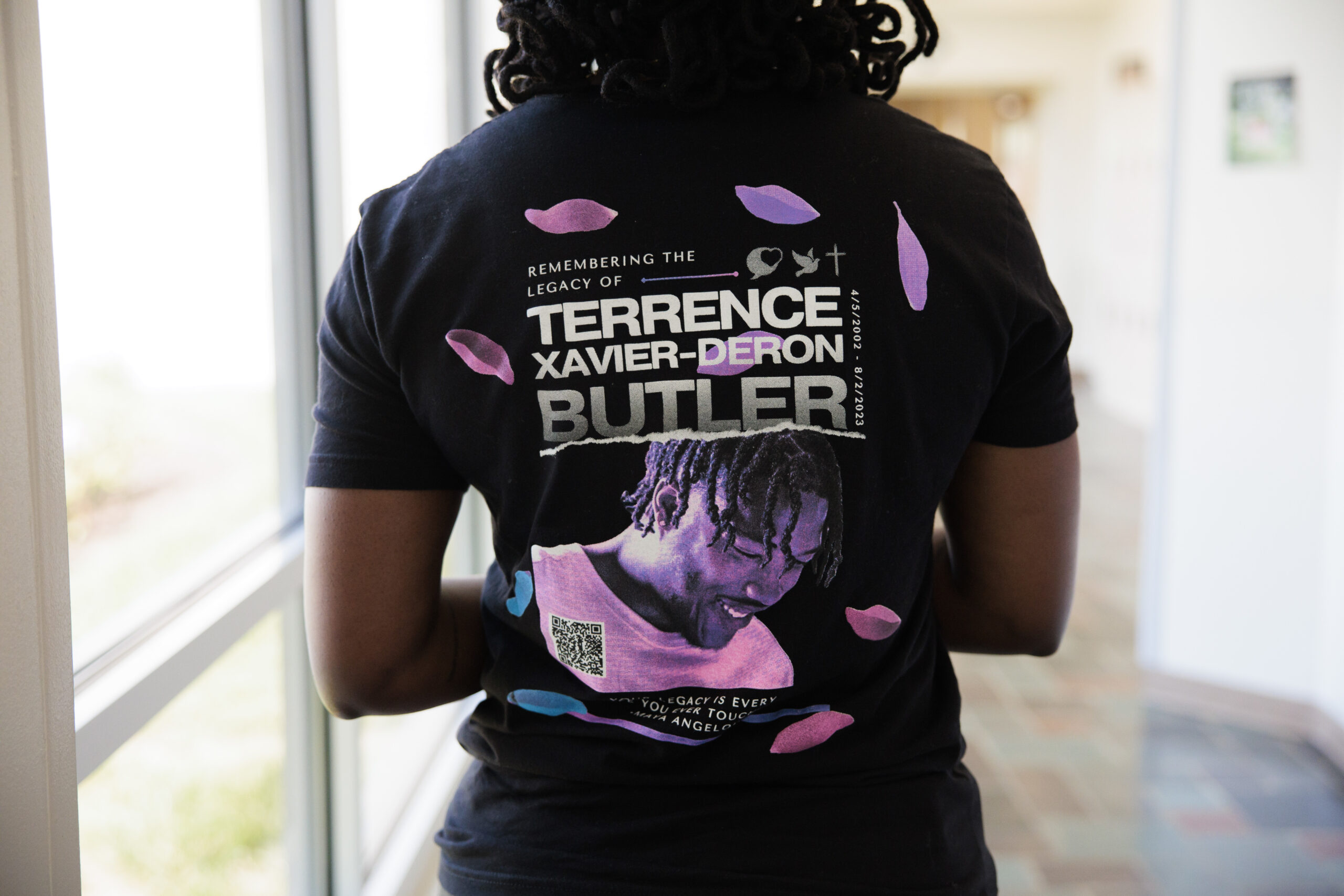

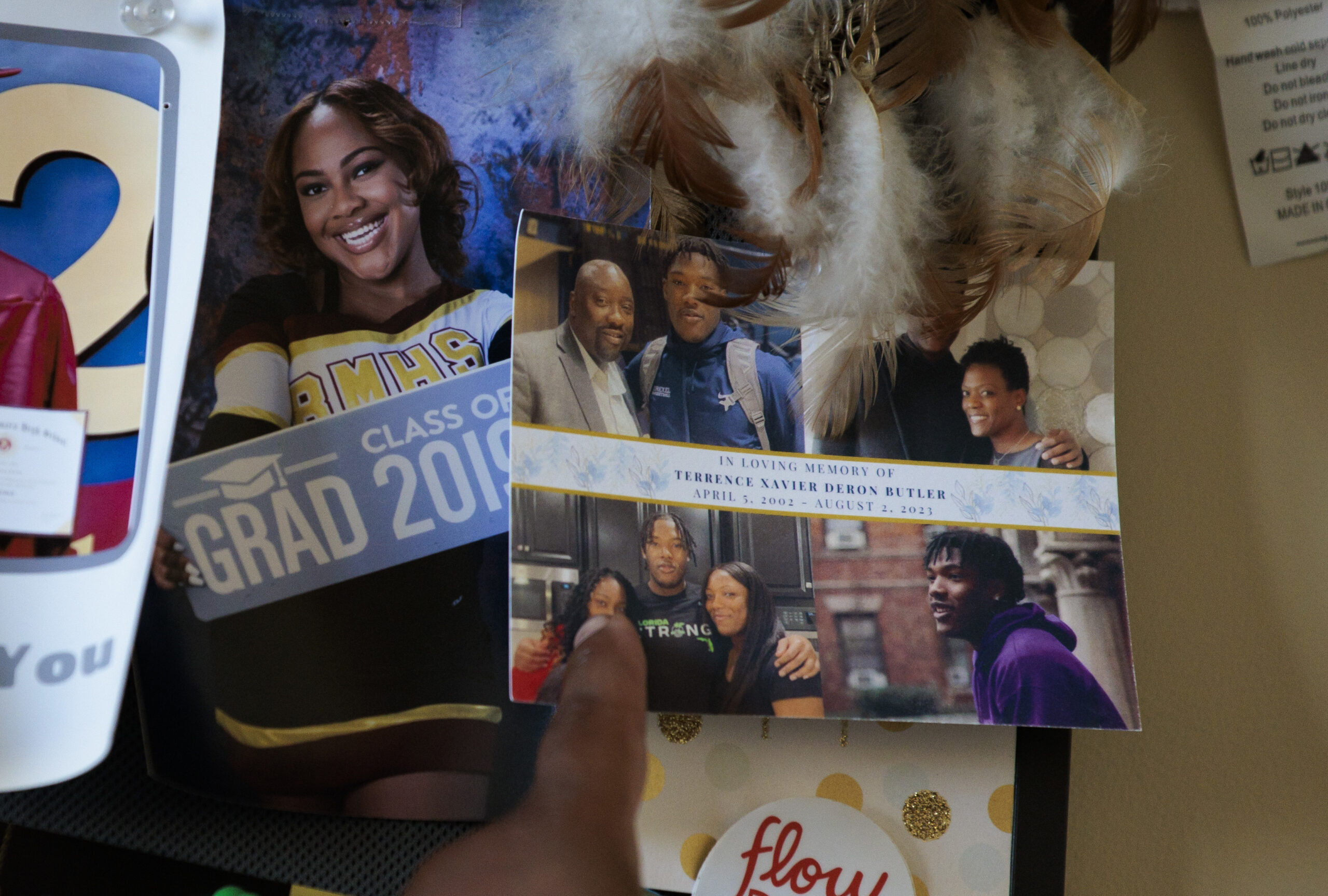

Terrence Butler’s college basketball career comprised just eight games over two seasons at Drexel. His death at age 21, on Aug. 2, 2023, was at once core-shaking to those who knew and cared for him and, after a few days, just another speck of troubling news during troubling times to those who did not. It marked one of the rare occasions in which someone, especially someone so young, had died by suicide and the manner of death was immediately acknowledged and publicly revealed.

Within 48 hours of the discovery of Terrence’s body, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health confirmed to media outlets that he had killed himself, for there was no way to euphemize it and no point in trying. The cold and clinical language of the medical report — that a “normally developed, well nourished … black man whose appearance is consistent with the reported age of 21 years” had died — left no space for doubt.

The reasons that Terrence had died … they were a different matter. They would remain shrouded in grief and incomprehension, in blindness born of love and admiration and disbelief that he was capable of such an act — in an innocent unwillingness or inability to see.

Like all those who die at their own hands, he was locked in battle with himself. It was a struggle whose scope and depth he alone knew, and only by tugging a thread of the tapestry of circumstances and events and achievements that were sewn together to form his too-brief life can anyone even attempt to make sense of its ending.

Why would anyone want to see the signs, after all? And who would have been capable of seeing them? Spiker couldn’t spot them on the day he met Terrence. No coach could. It was a camp at Drexel, just one stop on a tour of colleges and universities and programs for Terrence, and there he was, in the summer after his sophomore year at Bishop McNamara High School in Forestville, Md., grabbing a rebound in one pickup game inside the Daskalakis Athletic Center, scanning the court to throw an outlet pass, seeing no one open, pulling the ball down and dribbling the length of the floor to throw down a dunk himself. Spiker offered him a scholarship then and there. Take your tour. See those schools. Go through your process. Just remember: You have a home here at Drexel.

“We loved the skill set,” Spiker said. “We loved his motor, his size, typical basketball things. He was big. He was strong. He was respectful, a super-engaging, super-likable, smiling guy. Man, TB, he was a very impressive young man.”

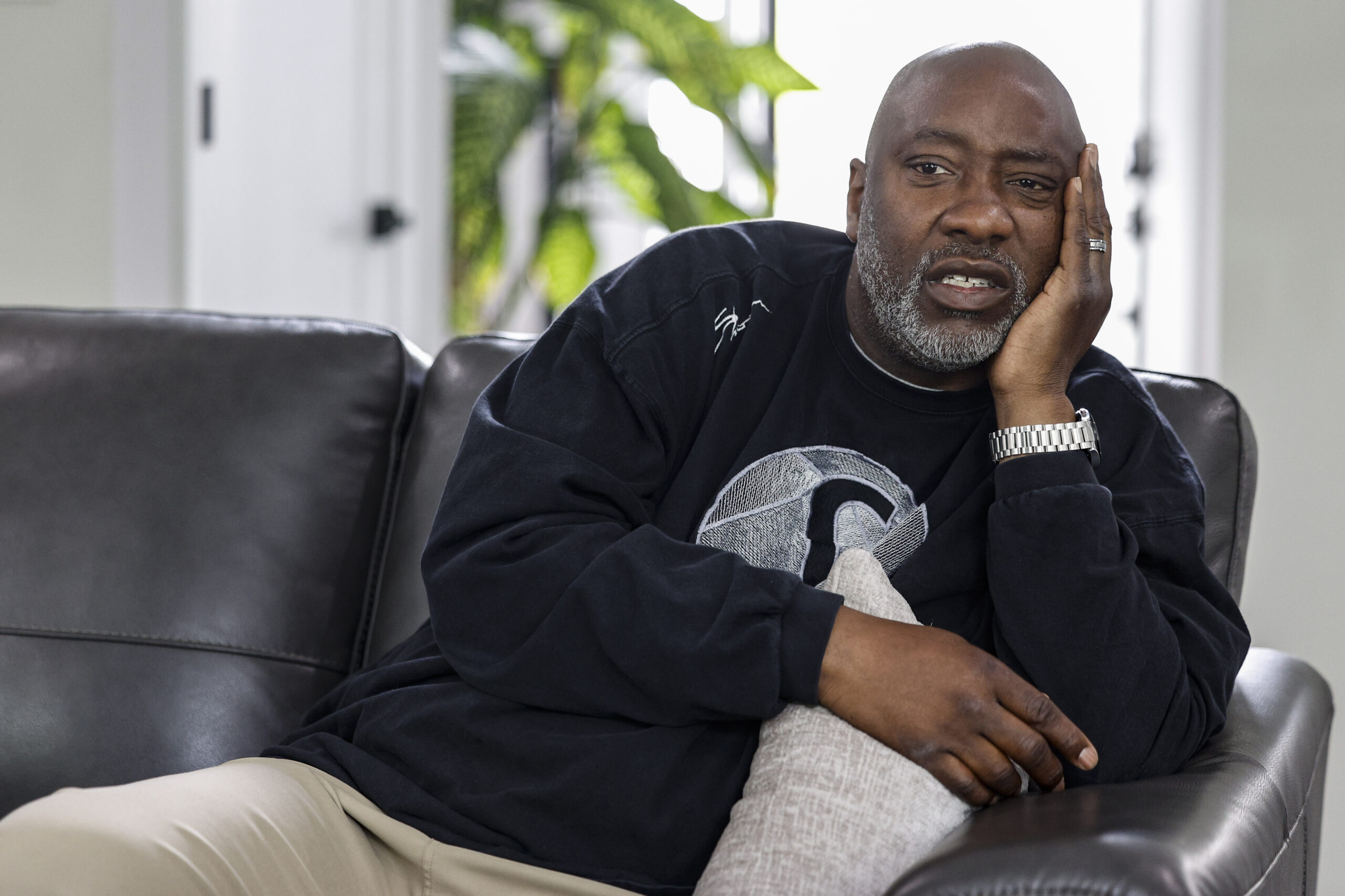

Terrence’s parents, Tink and Dena, had charted a particular course for him and his sisters to try to prepare them for the demands and rewards of the pursuit. Tink saw sports as the children’s primary path. Growing up near Washington, D.C., he had boxed in the AAU and Golden Gloves programs before entering the Army, which promptly sent him to Colorado Springs to train to make the 1988 U.S. Olympic team as a light heavyweight.

“Was doing well,” he said. “Winning all my fights.”

Except he dislocated his left shoulder. No one knew; he popped it back in and hid the injury from the coaches, for a while. He started fighting southpaw, throwing all his real punches with his right hand, faking haymakers with his left … except the shoulder popped out again, and he couldn’t hide it any longer, and he had to have surgery, and his Olympic dream vanished. “I don’t know how far I could have gone,” he said one day in his living room. “I probably would have won a gold medal.”

Dysfunction framed Dena’s early life. She was 2 when her parents split up, both of them alcoholics, her mother moving from Memphis to the D.C. region to escape Dena’s father. Tall for her age, Dena began driving when she was 10 and working when she was 14, putting the money she earned from fast food restaurant and retail jobs toward rent.

“I didn’t sleep as a child,” she said. “I never slept. I just couldn’t. There was always something happening, and I just decided not to live like that when I had kids. I didn’t want that for them. These can be cycles if you’re not intentional and deliberate about your choices. Your choices affect your kids. Every choice my parents made affected me.”

Once Dena and Tink met and got married and started their family, as he moved from one solid job to another — from a power-company technician to a crane operator to a D.C. government supervisor — and she settled in as a resources analyst for NASA, they established a certain culture, with certain norms and standards, for their children. There would be a consuming emphasis on academics and athletics and, more importantly to Dena, a balance of those two foci.

Tiara was born in 1992, and a second daughter, Tasia, arrived three years later, and the sisters grew up hearing the same daily phrases from Dena: TV will kill your brain. … Go look it up in the dictionary. … Smart people ask questions. … “But the biggest philosophy we learned,” Tasia said, “was ‘Work first so you can play later.’”

The playing came naturally to all of them. The only driving Tiara did when she was 10 was when she had a basketball in her hands and an open road to the hoop. She got her first Division I scholarship offer when she was 14, then picked Syracuse. Tasia preferred dancing — hip-hop, ballet, tap, jazz — to dribbling, but she followed Tiara to Syracuse on a full ride for basketball before transferring to James Madison.

The understanding that sports could be a vessel shepherding the two of them to college, to a terrific education, to stability and success in their lives was doctrinal among mother, father, and daughters. Family time morphed into basketball time, and basketball time morphed into vacation time, and there was less vacation time as life went on.

Tink, in fact, spent so many mornings and afternoons and nights in gymnasiums and arenas with Tiara and Tasia, became so familiar a presence at AAU tournaments and all-star camps, chatted with so many coaches and recruiters and shared so many tidbits and observations about players that he parlayed his daughters’ careers into a new profession. Into a scouting service. Into a subscription-based website: prepgirlshoops.com. Into more than $100,000 in annual revenue. After Terrence was born in 2002, he was a fixture in those gyms and near those courts just like his parents and sisters were.

“When he first started playing,” Tiara said, “he would run up and down the court, saying, ‘Look at me,’ smiling and leaping. Always passed the ball. So kind to teammates and opponents. He really just wanted the snacks afterward.”

He wanted to be “T.J.,” but it never stuck. His sisters shortened the nickname they had given him when he was a baby, “Man-Man,” to just “Man.” It was all they called him. By age 10, he was playing high-level AAU ball, growing on a vegetable-free diet of chicken nuggets and french fries. Heredity was on his side. Tink was 6-3. Dena was 5-10. “I’m thinking he’s going to be 6-6 or 6-7,” Tink said, “and Michael Jordan was 6-6.”

Tink took him to one football practice when Terrence was 11, to try to toughen him up. All it took was a helmet to the stomach in his first tackling drill to get him coughing and wheezing and whining, to have him decide he hated football. Good, Tink thought, now we can concentrate fully on basketball. So Tiara and Tasia — don’t let those soft features and sad eyes, just like their brother’s, fool you — would roughhouse Terrence in their one-on-one games.

“May have gotten carried away,” Tasia said.

‘We were a unit’

His sisters’ recruiting visits were groundwork-layers for him, at least in his father’s eyes. When he was 9, he got pulled out of the crowd at a Towson University game for a free-throw contest. He sank 12 straight, right in front of the cheerleaders. When he was in sixth grade, the family joined Tasia for a visit to the University of Miami, and men’s coach Jim Larrañaga took one look at Terrence, at a pair of prepubescent arms already showing muscle and definition, and said, I’m giving you an offer!

He did the AAU circuit: DC Thunder, DC Premier, Team Takeover, Team Durant. Tink would bounce from Tiara’s game to Tasia’s to Terrence’s; Dena was always at Terrence’s. So he’d call her for updates.

How’s he doing?

OK … Oh, wait. He just scored.

As the kids’ basketball schedules, especially Terrence’s, took up more days on the calendar, there were more dinners in restaurants, fewer at home around the table. But Tink and Dena still made time to serve in ministry at The Soul Factory, an evangelical church in Largo, Md., even serving as premarital counselors to engaged couples. “We were always on the road,” she said, “but we lived selflessly. We were a unit.”

Then, a potential setback: July 2016. The summer between his seventh- and eighth-grade years. An AAU tournament in Atlanta. He jumped, landed on someone’s foot, wrenched his right knee. A torn meniscus. Surgery. Nine months of rehabilitation.

The big private high schools in and around D.C. had been scouting him; the injury might scare them away. No. Bishop McNamara, just a five-minute drive from the Butlers’ house, followed through with a basketball scholarship. Affiliated with the Congregation of the Holy Cross, its campus a strip of gleaming modern architecture and emerald land in Prince George’s County, with an enrollment that its admissions officers limit to roughly 900 students in grades nine through 12, McNamara is one of the most respected high schools in Maryland. Its alumni include several professional athletes, an astronaut, and Jeff Kinney — the author of Diary of a Wimpy Kid. The school fit perfectly with Dena’s plan for her children, with the idea of segueing from sports to a career or vocation beyond sports.

In his first year at McNamara, Terrence was the only freshman to play varsity basketball. The following year, the school hired a new head coach, Keith Veney, who immediately made Terrence the centerpiece of the team. He called Terrence “T-Butts” and would push him to shoot more frequently, questioning him every time he passed the ball and ending up half-impressed and half-exasperated at the answer Terrence always gave: Because the guy was open, Coach.

Still, Terrence had the ball in his hands often enough to be named the Mustangs’ most valuable player as a sophomore. “He would pass up those shots on purpose,” Tink said, “so that it wouldn’t be about him. He liked the accolades, but he didn’t want the attention.”

What did he want? It was hard to know sometimes. From the time Terrence began playing, Tink would give him a dollar for every rebound he grabbed in a game. One day, he opened up Terrence’s bank and found $1,200. Other than the occasional game of Fortnite, the kid didn’t buy anything for himself, didn’t crave the trendy clothes or the coolest sneakers. “He was the banker,” Tasia said. “We’d ask him, ‘You have change for a $50?’”

He embraced McNamara’s dress code: shirt, tie, hair cropped close. At home, he’d sit down and read the Bible, watch CNN, make an offhand joke whenever Dena would wonder how he had done on a school assignment. Got an A. Could’ve gotten an A+ if I tried. He had one girlfriend in high school, but Tink was pretty sure that Terrence hadn’t done much more with her than carry her books to class and sit with her on a stoop. “Waiting for marriage,” Tink said.

Terrence towered over the student body yet managed to keep himself on his peers’ level. “He was just a cool guy,” said Herman Gloster, McNamara’s dean of students. “You would see him before he’d see you. He was a kid who you could feel coming down the hallway — tall, always smiling. It was like a light force was behind him. Very respectful. Never had a detention. Just a great spirit. If you didn’t like Terrence Butler, something was wrong with you.”

When McNamara shut down its building for the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, it kept its doors closed and its students learning virtually for 12 months, from the middle of Terrence’s junior year to the middle of his senior year. The administration created “The Mustang Mix,” clusters of faculty and students who would gather on Zoom calls to stay connected with one another.

“A lot of people were complaining that seniors weren’t coming to the mixes,” said Dian Carter, McNamara’s principal. “Terrence came every day faithfully. He was always on camera, making breakfast, frying eggs.”

Once the school reopened, it did so partially. Students returned on a staggered schedule based on where their last names fell alphabetically. Plexiglas dividers separated them at each cafeteria lunch table. The entire building was cleaned every Wednesday. “It was the craziest thing,” Carter said, and she could sense Terrence’s hunger to be around and engage face-to-face with his friends and classmates again. Ms. Carter, he’d ask her, can’t we come here every day?

Injury problems

The court was hardly a refuge for him. Throughout the first month of the lockdown, he and Tink searched for places where he could play and train. They found one guy who had a small private gym and was willing to open it. On a Sunday, Terrence was going full-court against some eighth and ninth graders, players younger and less skilled than he was, and one of them bumped into Terrence, and that brief contact was all it took. No, my knee! An MRI test confirmed it: He had retorn his right meniscus.

Another surgery, this one in April 2020. Another nine months without basketball. OK, Terrence could still be a McDonald’s All American nominee his senior year at McNamara … and was. Terrence could still be ready for the start of his freshman season at Drexel, and Spiker had remained loyal to him, had been the first coach to offer him a scholarship and had never rescinded it, had shown that he was authentic and real and that his word meant something. Terrence could still stand there inside the DAC in June 2021, alongside Drexel’s other incoming recruits, for a private ceremony honoring the Dragons’ conference-tournament title three months earlier, and he could hear Spiker say, I know you guys didn’t play in these games, but you’re part of this program. I’m super-excited you’re here to see this, and this is the standard we’re shooting for. Terrence could …

… no, maybe he couldn’t. During a workout just weeks after the ceremony, he tore his left meniscus — not as severe as his previous injuries, just a two-to-four-month rehab this time, but … Lord, three knee operations, and he hadn’t suited up for a single official practice for Spiker yet.

Rough as that misfortune was, Dena trusted that her son could handle it. “It was almost like he was always doing a self-examination to see if something resonated with him,” she said. “He had a mentality of ‘I could take it or leave it. I’m good wherever I am. If I choose to go to school, I can do that. If I choose to play ball, I can do that. If I choose to write novels, I can do that.’ He was never a person you could put in some type of box. He was completely different. You could not read him in that manner. He was like, ‘Wherever God leads me.’ He would just be in that moment. If he’s playing ball, he’s going to give you ball. If he’s in school, he’s going to give you school.”

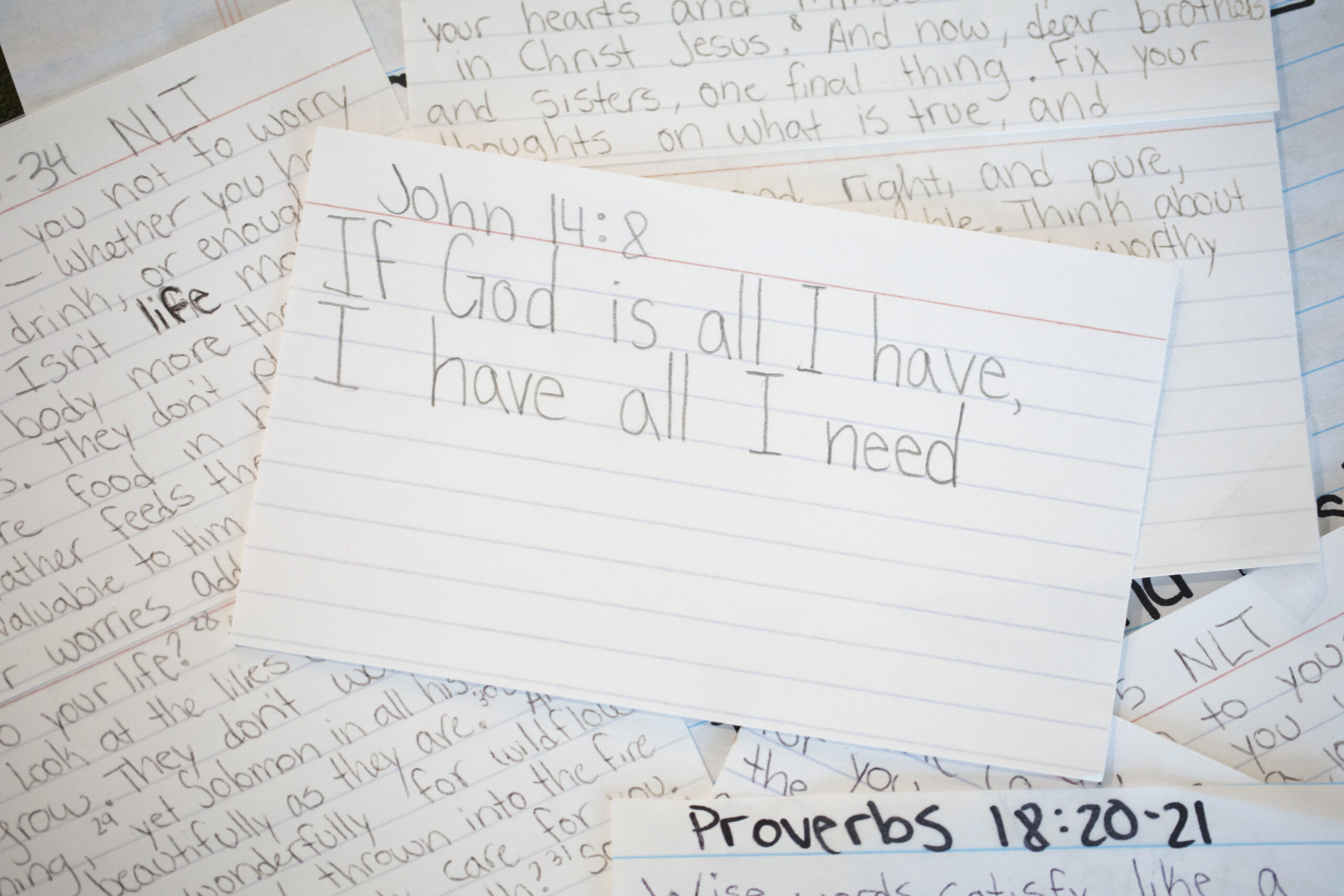

These were more than a proud mother’s words. Terrence wrote biblical verses in pencil on index cards and carried the cards with him. Galatians 5:16: So I say, let the Holy Spirit guide your lives. Then you won’t be doing what your sinful nature craves. There was no preaching or proselytizing, just the self-assurance of a person who appeared fully comfortable with himself. Is there a more appealing quality in a human being? It didn’t take him long to become one of the most popular figures on campus. He majored in engineering, joined Drexel’s chapter of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, and had the time and the opportunities to move within the university’s varied worlds.

Spiker would stop in at a coffee shop to grab a drink, and a student would recognize him and say, Coach, I know Terrence Butler. He’s one of the nicest guys I’ve ever met. So Spiker would take a selfie with the student and text it to Terrence, and Terrence would respond, One fan at a time, Coach. One day, the two of them strolled across campus, and Spiker felt like he was with a celebrity.

“It was two girls from the lacrosse team: ‘Hey, TB,’” he said. “It was two girls from the dance team. It was two guys from FCA. A lot of people identified with him. He knew as many people as the rest of our team combined. This dude was very outgoing and had a big reach.”

Imagine if he had been playing any meaningful minutes for the Dragons. Imagine what his reach would have been then. He’d set the coaches’ grease board in his lap, pick up a marker, and design plays for his teammates. He’d call his brother-in-law, Arthur, who was a personal trainer, and press him for insights and advice: What can I do to be the best athlete I can be, to strengthen my body so I won’t get injured again? Push-ups, sit-ups, stretching — he devised his own exercise routines.

Luke House, one of Terrence’s teammates and roommates, would join him for long weightlifting sessions that they’d pause only when Terrence set his face in “The Look,” House once wrote, which meant “it was time to tuck our shirts in because the weights were getting heavy.”

After one victory over Towson, after Terrence had spent two days of practice dragging his damaged leg up and down the floor, refusing to sit out, insisting on suiting up for the Dragons’ scout team, Spiker turned to one of his assistant coaches and said, I don’t think we win that game if TB doesn’t give us all he had. He was doing his best to contribute, to get back on the court. Everyone could see that.

Then in January 2022 he was running during a pickup game and felt his right knee pop and found out that he had torn that damned right meniscus for a third time.

The doctors and trainers recommended that he not play anymore. Tink called him. Did he want to transfer? Tink had been working the phones, talking to coaches in other programs. No, Terrence wanted to stay. Spiker and Drexel put him on a medical hardship scholarship. He could get his engineering degree, be part of the team in another role or capacity. I’m good, Dad, he said. I’m good.

Dena … well, it never crossed her mind that Terrence might transfer. She had attended all of his games at McNamara, and she attended every Drexel home game whether he played in any of them or not. And he would play just those eight times, never seeing the floor for more than 12 minutes in any of them, never pulling down more than five rebounds, never scoring more than two points. She attended every game even though she and Tink had been drifting from each other for a while, even though he was spending more time at work and at games — among Tiara and Tasia and Terrence and his scouting service and his tournaments and his website, where did business end and family begin? — even though they divorced in 2021.

It was raw. It was painful. It was the breakup of The Butlers — that’s how everyone knew them, spoke of them. The Butlers. They had been a unit, as Dena said, and now they weren’t.

Terrence was managing to handle it, as she trusted he would. At least he seemed to be managing. Spiker noticed nothing out of the ordinary. Still the same old TB. Still in good spirits. Still the same terrific student — he made the Colonial Athletic Association’s honor roll in 2022, the same year basketball stopped for him. In June 2023, he was taking a summer class, Introduction to Africana Studies, and earned an A on a five-page paper about the corrosive effects of American slavery. He wrote in part:

The solution begins with education and must start at a young age. … Until we start to seek knowledge and dig up the roots of America rather than trimming branches, black people will always be disproportionately affected, with no understanding why.

A month and a half later, Terrence took that train ride down to Maryland to visit his family. Tink was hosting a party at his house on the night of Saturday, July 29, for a world welterweight championship bout between Errol Spence Jr. and Terence Crawford — 70 people, food, drinks, a television on the outside deck. Terrence declined to attend, which didn’t strike anyone as unusual. People would have asked him about Drexel and basketball, would have made a fuss over him, and he wouldn’t have wanted to be an object of attention at such a large gathering. He preferred a quiet night at his sister’s house. Arthur offered to cut his hair.

Just before Terrence and Tiara left Dena’s house, the three of them gathered on the front stoop to snap a photo of themselves in the summertime’s evening light. But as he stepped outside, Terrence paused. Hold on, he said. I forgot something. He went back inside, reemerging after a few moments. The picture, in hindsight, is telling. Dena is in the middle. She smiles wide, her teeth sparkling white. Tiara, on the left, has a knowing, closed-mouth grin. Terrence towers above them. His face is stone.

He texted Dena at 9:19 a.m. Sunday to let her know that he had arrived safely. But on Wednesday, Aug. 2 — a cerulean, temperate, just perfect Aug. 2 in Philadelphia — Terrence missed a team breakfast. He was tracing a different academic arc from most of the other players, taking a full schedule of summer classes, on track to graduate in a year, while his teammates were taking a course or two. So Spiker chalked up his absence to his study habits, and it wasn’t until the guys started to murmur that they hadn’t seen him in a few days that Spiker began to wonder and worry.

He called and texted Terrence immediately. No response. He called Dena, who told him that she hadn’t heard from Terrence since he got back to Drexel. He called campus security and requested a wellness check and stayed on the phone while the officers unlocked and opened the door to Terrence’s bedroom and discovered that something horrible had happened.

When her phone buzzed and a police detective told her that her son was dead, Dena managed to ask, How? She listened to the answer, then ran upstairs. After she and Tink had divorced, she knew that she would be living alone, in a new house, in an unfamiliar neighborhood. So she had purchased a black .357 revolver for self-defense. All three of her children knew exactly where she kept the gun: out of sight, on the floor, under the headboard of her bed. She looked there. It was gone.

A terrible conundrum

At Terrence’s funeral, inside Zion Church in Greenbelt, Md., Tink and Dena stood side by side behind a lectern, holding hands, eulogizing their son. “I thank God for loaning him to us for 21 years,” Tink said during his short speech. Dian Carter, McNamara’s principal, had been on vacation, sunning herself on a beach near Houston, when she heard the news of Terrence’s death. No, she thought, that can’t be right. Terrence must have been attacked. Suicide? Terrence? What were the signs?

Now here she was, sitting and weeping among the congregation at Zion, and she had never seen anything like Tink and Dena’s gesture, their grip, that coming together of a couple who were now separate. She found it comforting, but it did not answer the question that Carter was still asking herself, the question that everyone in the church had to have been asking themselves: The worst thing that can happen to a family, to a young person in the prime of life, had happened to this family, to this young man. Why?

That is the conundrum that cuts to the core not just of Terrence’s death, but of suicide in the United States. There are so many contextual factors and contradictory trends that anticipating when someone might end his or her life or reaching a definitive conclusion about why someone did is akin to grasping at vapor.

Kelly Green, a psychologist and senior researcher at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, said in an interview that the most recent available data on suicides are from the same year that Terrence died: 2023. Medical examiners must report suicide deaths to states, and states must report them to the Centers for Disease Control, and the slow grind of that bureaucratic machinery causes an information lag.

“One of the frustrations is that we’re always a couple of years behind what’s happening now,” Green said. “We’re always playing catch-up.”

Though Green noted that suicide “is still a very low base rate event — it happens rarely” — its current has been flowing in a concerning direction. The overall national rate jumped 37% from 2000 to 2018, according to the CDC, dipped by 5% between 2018 and 2020, then peaked in 2022. It held relatively steady in 2023, when 14.2 out of every 100,000 deaths were suicides.

Terrence fell within the age range, 15-24, with the second-lowest suicide rate, which would cast his death as an awful anomaly. But the CDC has reported that, although men make up 50% of the population, they account for nearly 80% of all suicides, and among Black men, according to the American Foundation of Suicide Prevention, the rate climbed from 9.41 per 100,000 deaths in 2014 to 14.59 in 2023, which would cast Terrence’s death as one stirring of the sea in a destructive tide.

“I would go even a step further,” Derrick Gordon, an associate professor of psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine, said in an interview. “In the Black community, the data show that, traditionally, suicide was not seen as a Black thing. The norm has been, ‘That’s a white thing.’ It’s sometimes seen as the antithesis of the Black faith tradition. ‘My faith isn’t strong enough to help me get past this thing, and it should, and it’s not working.’ Faith doesn’t reduce the burden. It adds to the burden.

“For a long time, there was this myth: ‘We don’t have to worry about Black people and suicide. They’re at low risk. They have more community or are more connected to their faith — a lot of buffers to protect them.’ Well, we’re seeing that’s not true.”

Parents, siblings, loved ones: These would presumably be the strongest guardrails. But as Gordon noted, the factors that compel a person to attempt suicide are always unique to that person, and since even those closest to him or her often don’t pick up on any indications of deep distress, predicting or preventing a suicide is challenging at best and impossible at worst.

“Families never think of suicide as a possibility,” Gabriela Khazanov, a clinical psychologist and assistant professor at Yeshiva University in New York, said in an interview, and they can inadvertently create conditions that heighten the risk.

Terrence was one of the more than 49,000 people who died by suicide in 2023, according to the CDC … and one of the more than 55% of those who used a firearm to do it. The combination of suicidal thoughts and easy access to a gun can be lethal, in part because “it’s not that people who are suicidal want to die,” Green said. “It’s that they want to stop an intolerable situation or problem. They seek an escape,” and they are often willing to act without hesitation to relieve their pain.

A January 2009 study published by the Journal of Clinical Psychology showed that half of all suicide attempts result from less than 10 minutes of planning.

“The impulse might be quick, but the issue is, do you have means?” Gordon said. “I can think about it all I want to, but if I don’t have access to means, that’s an issue.”

Terrence Butler did have means, but it would be wrong to call his decision to use his mother’s gun impulsive. He had carried the revolver with him in his navy blue Drexel backpack on the ride from Dena’s house to Tiara and Arthur’s. He had kept it in that backpack for several hours at their home — kept it there overnight, in fact. He kept it there during the short car ride to New Carrollton Station and throughout the 1-hour, 45-minute train ride back to Philadelphia. He kept it there as he walked the three-fifths of a mile from 30th Street Station to The Summit, to a vibrant college setting in a vibrant city, and he kept it there as he opened the door to Apartment 208, to his living space with his personal effects and the memories they inspired.

It is one of the most excruciating aspects of his death: Terrence Butler had time to consider what he was going to do. He also had time to consider all the reasons, in his mind, that he had no choice but to do it.

Signs no one could see

Inside the dimly lit auditorium of Archbishop Carroll High School in Washington, some 150 parents, coaches, teachers, and administrators gathered on a night in October 2024 and learned about Terrence Butler from the women who knew him best. The school was holding a symposium about athletes’ mental and emotional health, and Dena, Tiara, and Tasia were the first speakers. They wore black T-shirts with his picture on them. Behind a table atop a stage, Dena sat between her daughters, one arm draped over Tiara’s shoulders, one arm draped over Tasia’s. There was an empty chair next to them, for Terrence.

Three siblings. Three honor students. Three Division I basketball players. A veneer of perfection, or as close to it as a family can get. And now …

“You can have all that,” Dena said to the audience, “and your child may not want to be there.”

Tiara and Tasia did not want to be there. Over the two years since Terrence’s death, the Butlers and others have plumbed their memories and searched within themselves for hints and connections that might help them explain the inexplicable. The sisters keep returning to their own childhoods and adolescence — to Tiara’s desire to draw and paint and write and Tasia’s to dance, to Tink training them to be competitive and never treat their opponents as friends, to Dena reminding them that athletics was their conduit to college, to the pressure they felt to perform.

Before every basketball game he played, Terrence would dash to the bathroom, as if he were seasick, and his hands would sweat so much that he could barely grip the ball. He’d douse them in powder to dry them only to have it turn into paste in his palms.

At Syracuse, Tiara often couldn’t eat before games because she was so nauseous from nervousness, then would shake as she sat on the bench. And it was only after her brother had died that Tiara confessed to her family that in her instances of greatest stress she would hear noises in her head — loud, indescribable noises — that she could not quell.

“I don’t really know where it came from,” she said, “but it showed itself in my body. It showed itself in my handshake. It showed itself with me being out of breath, with my voice shaking.

“I know what that feels like, what he was feeling. You can’t really control it. If you’re not playing, there’s that daunting feeling on top of that. Am I good enough to get on the court? Part of you is like, ‘OK, I didn’t play today, so I didn’t mess up today.’ But the other part, especially when you’re away from home and you didn’t play, is that you have to explain yourself to someone who’s not there and asks, ‘Hey, what’s going on?’ You’re thinking, ‘I’m working hard, doing all that I can do. It’s someone else’s decision.’ Now you’ve got to listen to that voice, too: ‘Hey, what’s really going on?’ It’s just a tough balance, especially as a kid. Then you’re going off to be by yourself, high level, lights always on …”

Guilt creeped into Tink’s thoughts. Was his children’s performance anxiety purely genetic, or had he pushed them too hard? Once, when Tiara wasn’t yet a teenager, she had moseyed after a rebound during a workout, and he chucked the ball to the opposite end of the gym and bellowed at her, “RUN!” When she came back, there were tears in her eyes and a whimper in her words. You yelled at me. He backed off some with Tasia, then backed off even more with Terrence — in his tone, but not in the time, the effort, the aspirations.

“My whole life was basically getting rebounds for him,” Tink said. “That was the plan from the time I saw I was having a son: I’m going to mold this guy into a basketball player.”

Dena second-guessed herself about how she and Tink handled their divorce. She had filtered all her parenting decisions through the lens of her own childhood, through the experience of growing up in a broken home, and she wanted to spare Tiara, Tasia, and Terrence any trauma. She and Tink had taken care never to argue in front of them, hiding the hard reality of their disintegrating marriage, opening up fully about the divorce only after Tink had remarried.

“I was playing God,” she said, “in trying to control everything so they wouldn’t see certain things.”

But the upshot was that, when the three kids finally found out their parents were splitting up, they were shocked. They never saw it coming, and Terrence was the youngest, the most impressionable, the baby of the family. In trying to protect them, had Dena failed to prepare them? Had she failed to prepare him?

“It could have handicapped them,” she said. “I’m supposed to be their training ground.”

She carried similar concerns once he went off to Drexel, and she wasn’t the only one. The pandemic had already isolated Terrence, pulling him away from his friends and his social life while he was still at McNamara, from an environment and experience that, even if the lockdowns hadn’t disrupted it, would have been its own kind of cocoon.

“Prince George’s County can give you a false sense when you leave here,” said Gloster, the McNamara dean — and a former police officer. “It’s a county of wealthy African Americans, and you don’t find many Catholic schools with so many Black students where parents are paying a tuition of $22,000. Then they get out in the real world, and it’s, ‘Maybe I’m too Black. Maybe I’m not Black enough. Maybe I didn’t realize there was a lot of racism in the world. Maybe I didn’t realize I had demons inside that hadn’t surfaced.’”

Now Terrence was living in an unfamiliar campus in an unfamiliar, more economically distressed neighborhood in an unfamiliar city, and whenever Dena or Tiara or Tasia saw a news story about violence in Philadelphia, one of them would call him. Hey, don’t go outside today. Dena would warn Terrence — 6-foot-7, 235-pound, Division I athlete Terrence — not to get into a stranger’s car, and Tasia would remind him that, as a Black male college student, he “fit the description of someone who could be in trouble.”

He could be a target for a criminal or a cop, could be taken for an easy victim or presumed to be a thug, so he should get to know as many people at Drexel as possible, make sure that everyone knew his face … starting with the campus police. His popularity was based on his personality, yes, but also on self-preservation.

Near the end of his freshman year, he confessed to Arthur that he was contemplating giving up basketball after college, even during college. He had realized that the sport at these levels was a business, and he wanted to enjoy the game, not have it be his job.

He had considered transferring from Drexel when Tink pitched him the idea, but no, he told his family — and himself — that being around the team, contributing to it whenever and however he could, and graduating with his engineering degree would satisfy him.

Besides, what guarantee would there be that he wouldn’t be trapped in limbo in another program just like he was at Drexel? Would transferring allow him to say goodbye to all the rehab and the ice packs and those platelet-rich-plasma injections, all those needles to his knees to stem the swelling and stoke some healing, and become the player he might have been? Would anything be different anywhere else?

But maybe he needed basketball more than he let on, more than even he understood or acknowledged. His faith calmed him only so much. Those biblical excerpts weren’t the only index cards he kept on his person at all times. He had others that were daily reaffirmations, prompts to remember that he mattered: I AM Valuable. I AM A Masterpiece. Even the white throw pillow on his bed, with a single word stitched across it, seemed to carry a double meaning. Whether asleep or awake, Terrence should RELAX.

He couldn’t. He asked Tiara to put him in touch with a therapist. She did, paying for his sessions. How much progress he was making, only he knew. He sought the counsel of Jordan Lozzi, the director of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes at Drexel and at Penn. On Nov. 28, 2022, Terrence sent a text message to Dena.

I do think I have a lot of unchecked thoughts. There are times where I know the truth but I try to solve everything on my own without guidance. I’ve been taking some baby steps here and there but I feel like I’m moving in slow [motion].

On March 10, 2023, he texted Dena again, confirming what he had earlier said to Arthur about his future, or lack of one, in basketball.

To be honest, it does not necessarily bother me that I’m not playing because I don’t have a passion to continue playing basketball after college. I’m still in the process of learning that my identity and worth [do] not come from basketball.

Later, another message to his mother:

I’ve always had this idea in my head that I needed to be perfect, and whenever I miss the mark or mess up in any way it messes with my head. It kind of reminds me of how I would feel after most games I played growing up. It’s difficult for me to focus on the good that comes out of situations. I may recognize it but the overwhelming negativity clouds the positive.

Dena responded at length.

I appreciate your honesty and transparency. You are not in denial about where you are which gives the Holy Spirit something to work with. Here is something that should support you in dealing with the spirit of perfectionism.

Possible things you’ll need to accept: that you’ll never be perfect and neither will your projects, but since life is about God — not perfect projects — this isn’t really a big deal.

Possible things you’ll need to confess: that you’re making something more important than God wants you to make it, that you’re seeing yourself through the culture’s eyes rather than God’s eyes, that you’re hurting others in your quest for perfection, and that you don’t have time to do the things God wants you to do because you’re too busy trying to be perfect.

She suggested that he consult the Gospel of Matthew, to remind himself that God would comfort him. Then she concluded her text:

Your goal is to please God. He is your source and once you understand that and align with His trust and what He says about you, He will cause the people to follow His plan for your life.

She keeps screenshots of these messages on her phone. They provide her no solace, no consolation, and no explanation. In November 2024, she contacted Lozzi, texting him four questions about what Terrence might have shared with him during their conversations and what actions Lozzi did take or could have taken to help him. The answers were revealing.

Terrence, Lozzi told Dena, “disclosed that he had harmed himself” sometime in April 2023, not long after he turned 21; Lozzi provided no details about how. Terrence had said it was the first time he had done anything like that.

Dena asked Lozzi if he was mandated to report any such occurrences of self-harm to a licensed therapist.

“In the college space,” Lozzi wrote, “we are mandated reporters, but I believe there is no mandated reporting for self-harm with adults. The mandated reporting in the college space is around sexual violence or relational abuse. To connect someone to suicide watch from my understanding they must be a present danger to themselves. In any of my interactions with Terrence I don’t believe there was anything that would have qualified to admit him to suicide watch.”

Lozzi was asserting that he wasn’t allowed to tell anyone that Terrence had committed harm to himself — that because Terrence was an adult, either Lozzi or a mental-health professional would have needed Terrence’s consent to disclose the incident to Dena, to another therapist, to anyone else, and Terrence had not given that consent. In his final text to Dena, Lozzi wrote that he “did propose for [Terrence] to see Drexel’s school counselors.”

When asked via email earlier this year if he would speak on the record about Terrence’s death, Lozzi responded that he had “sent your request to the appropriate person to get in touch with you right away.” He had forwarded the message to Hamilton Strategies, a public relations firm that represents the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. “Unfortunately,” an executive with the firm said in an email, “Jordan is unable to interview for your story. Thank you!” A second request for comment, sent in November to Lozzi and the executive, went unanswered.

The struggle of hope

The why of Terrence Butler’s suicide eludes everyone who loved him. Tiara teaches art at Bishop McNamara, her brother’s alma mater, and most of her students don’t know about Terrence’s death unless she mentions him, and once she does, sometimes one of them will approach her in her classroom and say, I just wanted to give you a hug. Tink will break down over his son once or twice a day, then just continue with his office work. He still asks himself haunting questions: How much did the divorce affect Terrence? How much did the knee injuries affect him? Did he consider himself a burden to his parents, as if he owed them a debt for all the time they had spent with him and money they had spent on him — a debt that he could never repay?

After Philadelphia police had ruled Terrence’s death a suicide, Dena said, she pleaded with them to unlock his cell phone. Perhaps he had written something in his notes app. Perhaps he kept a meaningful or revelatory photo stored in it. But the police, she said, told her that they would do that only in an open investigation — a homicide, for instance, in which they were trying to find and extract evidence. Here, they already knew what had happened, even if no one else really does. The department’s public affairs office did not respond to an inquiry about how, in general, police handle such situations.

Having the service provider unlock the phone wouldn’t accomplish anything either, Dena said, because only Terrence knew the passcode; resetting the phone without the code would erase all its data. She recently had the phone disconnected. It was a bitter symbol of the absence of closure.

“What I struggle with the most to understand in all this,” she said, “is that my son was devoid of hope, that he was in such despair, and he didn’t want anybody to help him. As a mom, to know your child didn’t have hope anymore … and hope is what gets us. Hope is what propels us. Hope is the motivator for why we keep going. And to know he didn’t have that, that’s hard.”

Zach Spiker finds himself slower to anger whenever one of his players happens to be late for a team meeting, for a practice, for anything. “I just want to make sure they’re safe,” he said. “Then we talk about it.” He saw a counselor himself, just a few sessions. “I had to,” he said. “I need to figure out things. I still have questions. There are still breadcrumbs, and you want to solve the mystery.”

They hoped that they had on the day that Terrence died. That night, 11 people crowded into his apartment: Dena, Tiara, Tasia, Tink and his wife, cousins and close family friends. Everything in the place was clean. There was nothing on his bed but a bare mattress. “You would have never known,” Tiara said later.

Tasia peered into the bedroom trash can. It was empty. She noticed Terrence’s Drexel backpack next to his bed. She picked it up, brought it into the living room, plopped it on the floor, and began rifling through it. She found random items, things that one would expect to find in a college student’s backpack: Terrence’s schoolwork, his headphones. Then she found something else.

The spiral 5×7 notebook, more than a half-inch thick from its 160 pages, was buried at the bottom of the bag. Tasia stopped. Tiara recognized the book, that sky-blue cover that she had glimpsed just four days before: It’s the same one he was writing in when he was at my house. Across the cover, Terrence had printed two words in black marker: My Brain.

This was it. This had to be it. This was Terrence’s journal, so this had to be the missing piece, the unknown explanation. Everyone in the apartment froze, went silent, then sat down. Tasia opened the book.

On the first page, on the top line, Terrence had written, I’m sorry. I really tried.

On the second page, on the top line, he had written, The noise is too loud.

On the third page, on the top line, in the top left-hand corner, he had written just one letter, just one word: I.

Tasia turned the page. And the next page. And the next. The family waited for a revelation that would never come. There were 157 pages remaining in the notebook. Terrence Butler had left all of them blank.