BALTIMORE — Dr. Oz, mouth full of quinoa, paused midbite.

He motioned a nearby videographer to a spot behind the tent where he and celebrity chef Geoffrey Zakarian sat tasting entries in a staff cooking competition. It was a better angle to capture dozens of employees watching them in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services headquarters parking lot that August day.

The famous television doctor Mehmet Oz hasn’t left the stage. He has found a new one as he runs the federal agency that spends $1.5 trillion a year and oversees health insurance for almost half of all Americans. Instead of a New York City studio, Oz spends his time in drab government buildings. But Oz says his ability to reach people is why President Donald Trump wanted him for the job.

“He’ll say, ‘Oz, he was good on TV. It’s a good sign if you’re on TV because it means people can listen to you and you’re making sense to them,’” he said in his first wide-ranging interview as CMS administrator.

Oz’s ability to reach an audience is undisputed. But he now faces a test of whether showmanship and affability can win over public support as he guides major Medicaid changes, oversees soaring costs of Affordable Care Act plans, and contends with the nation’s chronic malady: paying exorbitant prices for mediocre results.

The issues Oz confronts are among the wonkiest in the federal government, with the lives of millions of Americans at stake. His ability to communicate and charm has earned him praise, even from critics skeptical of a man once summoned before senators for hawking “magic” weight loss from a coffee bean extract. Some of his predecessors under Democratic presidents, with whom he regularly consults, and many at the CMS and in the health industry say he has displayed policy expertise and been effective at boosting morale at his agency.

“I’ve been impressed,” said Andy Slavitt, who was CMS acting administrator under President Barack Obama. “He’s taken it very seriously.”

Oz’s name still provokes eye rolls among some health advocates and Democrats. “Nobody who’s serious in this country takes Dr. Oz seriously,” House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) recently said.

Critics also say Oz brings with him concerns about his investments into companies that could be regulated by the agency he leads, such as those offering drug discounts, supplements, and AI health technology.

The renowned heart surgeon is better known for his pageantry during 13 seasons of “The Dr. Oz Show,” where he told viewers how to eat more protein or handle menopause. He’s the only administrator since CMS was established in 1977 with no experience in health policy or economics. His only foray into politics was a failed Pennsylvania Senate bid in 2022.

Oz acknowledges that his ascent from television star to the head of a highly technical government agency is surprising. “Of all people, what?” Oz said.

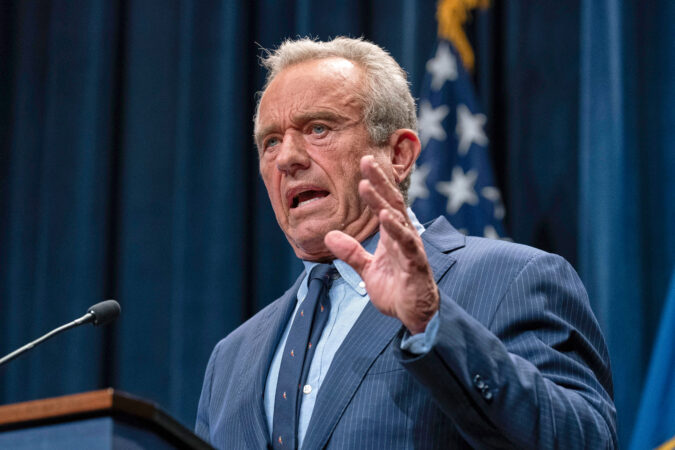

Oz’s central role in implementing cuts to public insurance programs and defending his polarizing boss, Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has drawn sharp criticism.

“Maybe he makes funny jokes and he’s a good hang,” said Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.), a longtime member of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee. “That doesn’t mean that what he’s doing isn’t pure evil.”

Yet some policy experts said that compared to the tumultuous layoffs, leadership turmoil, and infighting at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, and the National Institutes of Health, Oz’s agency appears less chaotic — at least so far.

“Out of all of those agency leaders, I think Oz is probably doing the best,” said a former Biden administration health official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to speak candidly.

From surgeon to celebrity to CMS

Oz is used to career makeovers.

The pioneering cardiac surgeon launched his eponymous show in 2009. On it, he sometimes leaned into the sensational, undergoing a colonoscopy on-screen and entertaining unproven ideas, including that cellphones cause cancer and zodiac signs influence health traits.

But Oz centered the show on the notion that people should control their health through diet and exercise — a precursor to Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again movement. He explored how poor gut health and chronic inflammation could cause disease, an idea affirmed in peer-reviewed studies. He urged viewers to stop eating processed foods and promoted bone broth and Greek yogurt.

“The MAHA movement was that on steroids,” he said.

In 2016, Trump went on Oz’s show during his presidential campaign to release a letter from his doctor attesting to his health. Six years later, Trump’s endorsement helped Oz win the Republican nomination to run for an open Senate seat in Pennsylvania, though he lost to Democrat John Fetterman.

Oz’s connection to Kennedy goes back even further to a 2010 clean water event in Utah where they skied together. He interviewed Kennedy in 2014 on his show about potential dangers from the vaccine preservative thimerosal, which scientists have deemed safe. During the segment, Oz told pregnant women to take a thimerosal-free nasal flu shot instead.

After Kennedy ended his independent presidential bid to endorse Trump last year, he and Oz threw Trump a fundraiser at Oz’s Pennsylvania home. Oz regularly hosted Kennedy at his Palm Beach, Fla., home as they awaited Senate confirmation.

As Oz tells it, health insurance is “a bit of an away game” for Kennedy. Shortly after the November election, Oz recalls Kennedy saying he was really excited about every part of running HHS — except for the highly technical health insurance programs under CMS’s purview.

‘That crazy guy from TV’

After Oz took the helm of CMS, some questioned whether he would be up for learning its soporific machinery — a job that requires drilling into such doze-inducing terminology as medical loss ratio and bundled payments.

“There was a fair amount of skepticism among people in the beginning, like, Dr. Oz, he’s that crazy guy from TV,” said CMS deputy administrator Kim Brandt, a Trump appointee who worked at the agency during his first term.

Oz, who has medical and business degrees from the University of Pennsylvania, said he has “always been a bit of a wonk” on health policy and enjoys thinking about how the health system works as a whole.

“He’ll sit and talk to you about something like surety bonds for 30 minutes,” said Brandt, whom Oz has dubbed “Kimba.”

He said he started compiling a health policy “bible” for himself as soon as he learned he would be nominated, calling past CMS leaders to learn how the agency works. He has talked many times to Slavitt and Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, who was CMS administrator under President Joe Biden.

And he surrounded himself with deeply experienced senior staff and worked to prevent infighting.

“Don’t waste time on battles that drain you of chi,” he said.

He has been steering the agency in its own wonky way toward Kennedy’s goals of reducing chronic illness, finalizing a Medicare payment rule in October aimed at nudging doctors away from surgeries and toward prevention.

Rep. Richard E. Neal (Massachusetts), the Democratic leader on a committee overseeing health agencies, said he viewed Oz as a moderating force after lawmakers on his panel met with the administrator over the summer.

“He didn’t come across as being radical,” Neal said. “Largely because he’s a real scientist, a real doctor.”

Oz is also by far the richest person in recent history to run CMS, with a net worth between $100 million and $300 million, according to a review of his financial disclosures and previous administrators’ backgrounds. His past financial ties — and the millions he has invested in health insurers, pharmaceutical companies, and other health firms — raise questions about how deeply he has profited from industries he now regulates.

He previously advised Eko Health, a company whose AI-enabled heart monitoring device CMS recently approved for funding amid a broader embrace of AI health technology. A CMS spokesperson didn’t explicitly answer whether Oz recused himself from the decision but said he “abided by all of his recusal obligations.”

Last year he co-founded ZorroRX with his son, Oliver, which aims to profit from a drug discount program overseen by a separate branch of HHS — but which could move to CMS under a pending restructuring plan.

Oz said he has divested all of his holdings in healthcare. “There’s not a single thing left in my portfolio which I have any involvement in,” he said.

But Oz also said he transferred his holdings in ZorroRX to a trust managed by Oliver, who is still involved in the company.

Oz also held millions of dollars of stock in iHerb, a wellness company that sells direct-to-consumer folinic acid supplements and other products. At a news conference on autism in September, Oz, along with Trump and Kennedy, praised leucovorin, a highly concentrated folinic acid medication requiring a prescription, as an effective treatment. HHS stressed in an X post that they are different products, after critics questioned on social media whether Oz stood to profit.

CMS spokesman Christopher Krepich said Oz complied with government ethics rules in divesting his ZorroRX and iHerb holdings, but Krepich did not answer whether he transferred his iHerb stock to his son or another relative.

Selling GOP policies

Establishing new Medicaid rules under Trump’s sweeping domestic policy law and selling them to the public poses one of Oz’s steepest challenges. The law, estimated to cut Medicaid spending by $911 billion over a decade, has alarmed Democrats and healthcare advocates, who say millions will be harmed by its work requirements, cuts to states’ funding. and new barriers to enrolling.

Oz emerged as one of the Trump administration’s top advocates for the changes, repeatedly dismissing projections by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office that 10 million more people will be uninsured under it.

He has been assuring states that tapping into better health technology will help limit coverage losses, touting plans for a CMS app for Medicaid beneficiaries to quickly report to states how many hours they worked, volunteered, or attended school in a given week to qualify for the insurance.

Oz rarely gives a speech without championing health technology, painting a picture of how it can improve care. He revealed in July that CMS would partner with Google and other tech companies in a “digital health ecosystem” to ease sharing of health information.

Slavitt, the CMS administrator under Obama, said in their conversations Oz tells him about leveling the playing field for “insurgent” smaller tech innovators to compete with “incumbent” healthcare giants such as Epic or UnitedHealthcare.

Oz has also played defense on another hot-button issue vexing Democrats: the expiration of pandemic-era enhanced subsidies for insurance plans sold through the Affordable Care Act, which sparked the longest government shutdown in history. Millions of Americans will have to pay hundreds or thousands more for monthly premiums after the extra subsidies expire Dec. 31.

Oz has stressed the subsidies were always meant to be temporary and noted they prompted more fraud in the marketplaces.

“It’s hard to disentangle Oz with the actions of the Trump administration broadly,” said Anthony Wright, executive director of Families USA, a consumer healthcare advocacy organization. “He is a main point person for many of the policy changes to make it harder to get on and stay on coverage.”

Oz has walked a fine line, supporting Trump and Kennedy but sometimes smoothing over controversial things they say.

Oz said it’s unfair to call Kennedy, the founder of an anti-vaccine group, “anti-vax” because he questions vaccine safety. He shares Kennedy’s view that the medical establishment has been too reticent to adjust to new evidence.

“That’s one of the hardest things to do in medicine: change your mind,” he said.

But as Kennedy built a career around vaccine skepticism, Oz hewed more closely to the experts. As Kennedy slammed the coronavirus shots, Oz told his viewers to get them. Unlike its sister agencies, CMS hasn’t pulled back on vaccines other than lifting a requirement that hospitals report COVID vaccinations among staff.

When Trump claimed an unproven link between Tylenol and autism, Oz adopted a more measured tone.

After the president repeatedly told pregnant women to avoid Tylenol, Oz told Newsmax that “of course” pregnant women should take Tylenol for a high fever if a doctor tells them to. On “TMZ Live,” he said Tylenol may be the “best option” for fighting lower-grade fevers during pregnancy.

Charming his audience

But Oz has a more basic goal than playing defense for his bosses. He said his chief aim is to improve outreach to people enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid.

“The most important accomplishment at CMS — if I can pull it off — is to talk to our customers,” Oz said.

He finds the Medicare enrollment booklets “dense” and wants to reach more seniors with an email newsletter instead. He made videos with Martha Stewart and Tony Robbins discussing aging. He pretended to call the Medicare hotline to enroll the day after his 65th birthday.

A team of photographers and videographers often tails him, ready if he has a spontaneous idea for a social media post.

Several hours after the cooking competition, Oz trekked to a roomy basement studio on the CMS campus to record videos promoting Medicare and marketplace enrollment.

Standing in front of a green screen, he launched into the first line as though introducing his show: “Medicare open enrollment is coming in hot.”

For a final video, he removed his jacket to demonstrate yoga moves for seniors.

Oz wants his staff to embrace this camera-ready strategy too. Medicare director Chris Klomp recounted running late at night when Oz called him to coach him on a media appearance.

“He believes in the ‘Fox & Friends’ model,” Klomp said, referring to the morning TV show that regularly features three hosts. “It shouldn’t just be the Oz show.”

Four CMS career staffers said he has been good for morale and more visible than past administrators, although some of them have misgivings about Kennedy and Trump.

He attended an employee Zumba class. Last spring, he was “mobbed” by staff during a lunchtime walk around the Baltimore campus, according to Dora Hughes, a career staffer who directs the CMS Center for Clinical Standards & Quality. Oz held a competition over the summer to see who could clock the most steps. He offered tips for “crushing cubicle cravings” during the holiday season as part of a regular agency update e-mailed to staff. “You don’t have to try every cookie on the cookie table,” he wrote.

As he browsed a farmers market in the CMS parking lot in August, a woman giggled as he donned her bright red glasses and posed with her for a photo. Born to Turkish immigrants, he spoke to another woman in Turkish.

Oz is “hard not to like,” said one CMS career employee who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to reporters.

“Part of me thinks it’s a facade,” the employee said. “And part of me thinks it’s a little reassuring.”

Rebecca Adams contributed to this report.