Penn’s graduate student workers have reached a tentative agreement on a first union contract, averting a strike.

The two-year tentative agreement includes increases to wages among other benefits.

“I am so proud of what we were able to accomplish with this contract,” Clara Abbott, a Ph.D. candidate in literary studies and member of the bargaining committee said in a statement. “We won a historic contract that enshrines gains for grad workers.”

Research and teaching assistants at the university voted to unionize in 2024. The union, which represents about 3,400 graduate student workers, is known as Graduate Employees Together-University of Pennsylvania (GET-UP) and is part of the United Auto Workers (UAW). The union has been negotiating with the university since October 2024 for a first contract.

In November, the union’s bargaining members voted to authorize a strike, if called for by the union. In January, they set a strike deadline, announcing that they would walk off the job on Feb. 17 if they had not reached a deal.

A deal was announced in the early morning hours Tuesday.

While tentative agreements had been reached on a number of issues, some remained without consensus ahead of the final bargaining session on Monday before the strike deadline. Those sticking points included wages, healthcare, and discounts on SEPTA passes.

“We are pleased to announce that a tentative agreement has been reached between Penn and GETUP-UAW,” a university spokesperson said in a statement. “Penn has a long-standing commitment to its graduate students and value their contributions to Penn’s important missions. We are grateful to all the members of the Penn community who helped us achieve this tentative agreement.”

A date to vote on the ratification of the tentative agreement has not yet been announced.

The deal comes as earlier this month Pennsylvania state senators and representatives and Philadelphia City Council members addressed letters to the university’s president and provost, urging them to come to an agreement with the student workers and avoid a strike.

“A strike at the University of Pennsylvania would seriously disrupt life for the tens of thousands of Philadelphians who are students, employees, and patients at Penn,” the letter signed by City Council members reads. “As such, we strongly urge the Penn administration to avert a strike by coming to a fair agreement that meets the needs of graduate student employees prior to February 17th.”

What’s in the tentative deal?

Monday’s bargaining session brought tentative agreements on sticking points that included wages and healthcare coverage.

If ratified, the tentative deal would provide graduate student workers with an annual minimum wage of $49,000, which the union has said is a 22% increase over the previous standard. For those paid on an hourly basis, the minimum hourly rate would be $25. Those rates would go into effect in April and a 3% increase would be provided in July 2027.

The deal would also create a fund with $200,000 annually from which graduate student workers could seek reimbursements to cover up to 50% of their dependent’s health insurance premiums.

Ahead of the Monday bargaining session, other tentative agreements had come together around leave. The university agreed to give six weeks of paid medical leave, as well as eight weeks of paid parental leave.

The university and the union had also recently reached a tentative agreement that would create an annual $50,000 fund to help international graduate student workers with expenses associated with reinstating or extending visas.

What would have happened in the event of a strike?

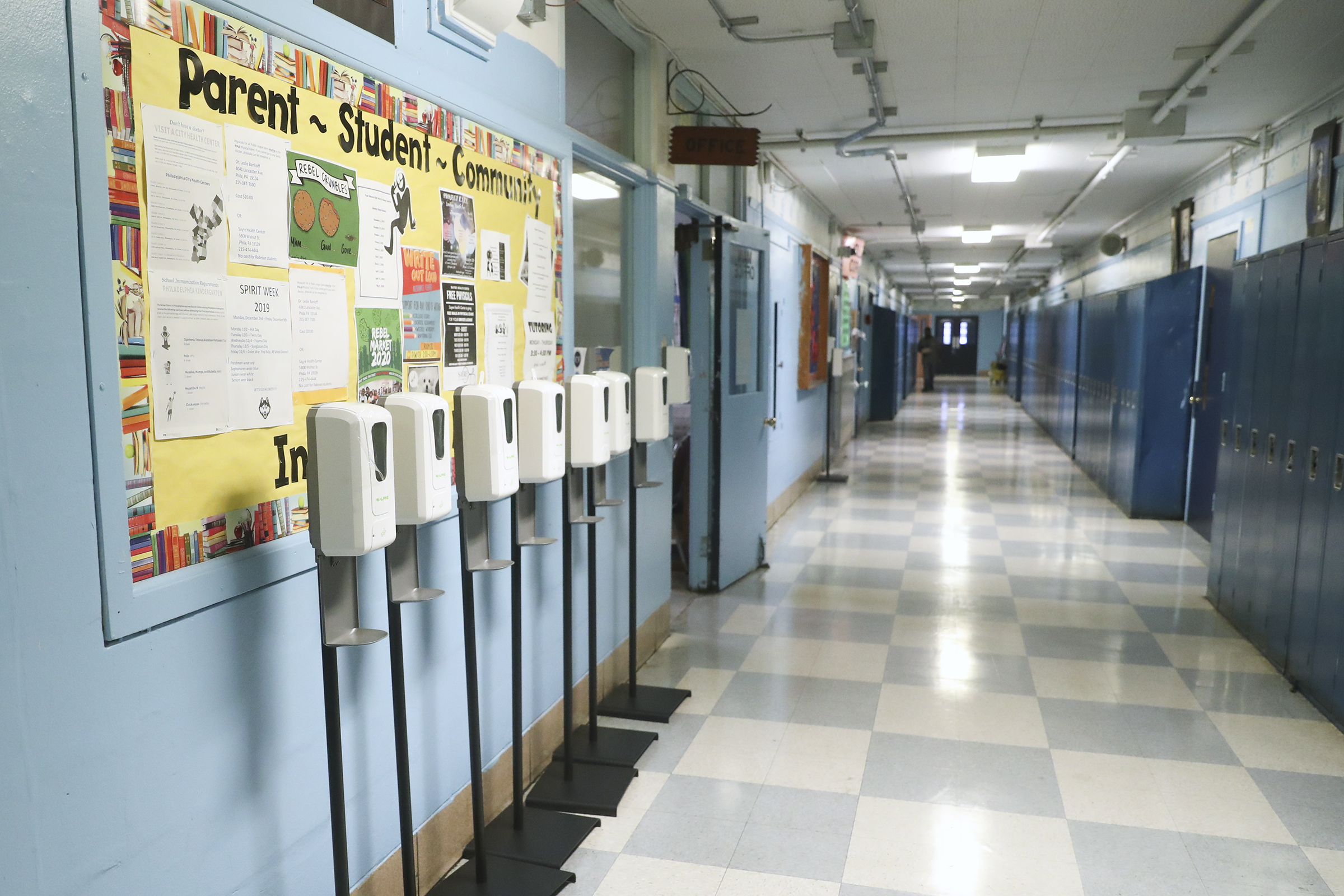

Graduate student workers in the bargaining group teach and conduct research at the university.

Classes, research, and other academic activities would have continued during a strike, according to the university spokesperson. Penn published guidance on how to continue this work in the event of a work stoppage or other disruption.

Striking graduate student workers would not have been paid throughout a work stoppage, but would have continued to be covered by their health insurance for the time being, according to a university statement.

If others employed at the university who are not in the bargaining group chose to join the work stoppage, they would not have been paid and could have faced consequences “up to and including separation from that position, depending on the circumstances of the refusal to work,” according to a university statement.

Ahead of the tentative agreement on Monday, hundreds signed a pledge indicating that they are employed at Penn and would not do the work of those on strike or assign it to others in the event of a work stoppage.

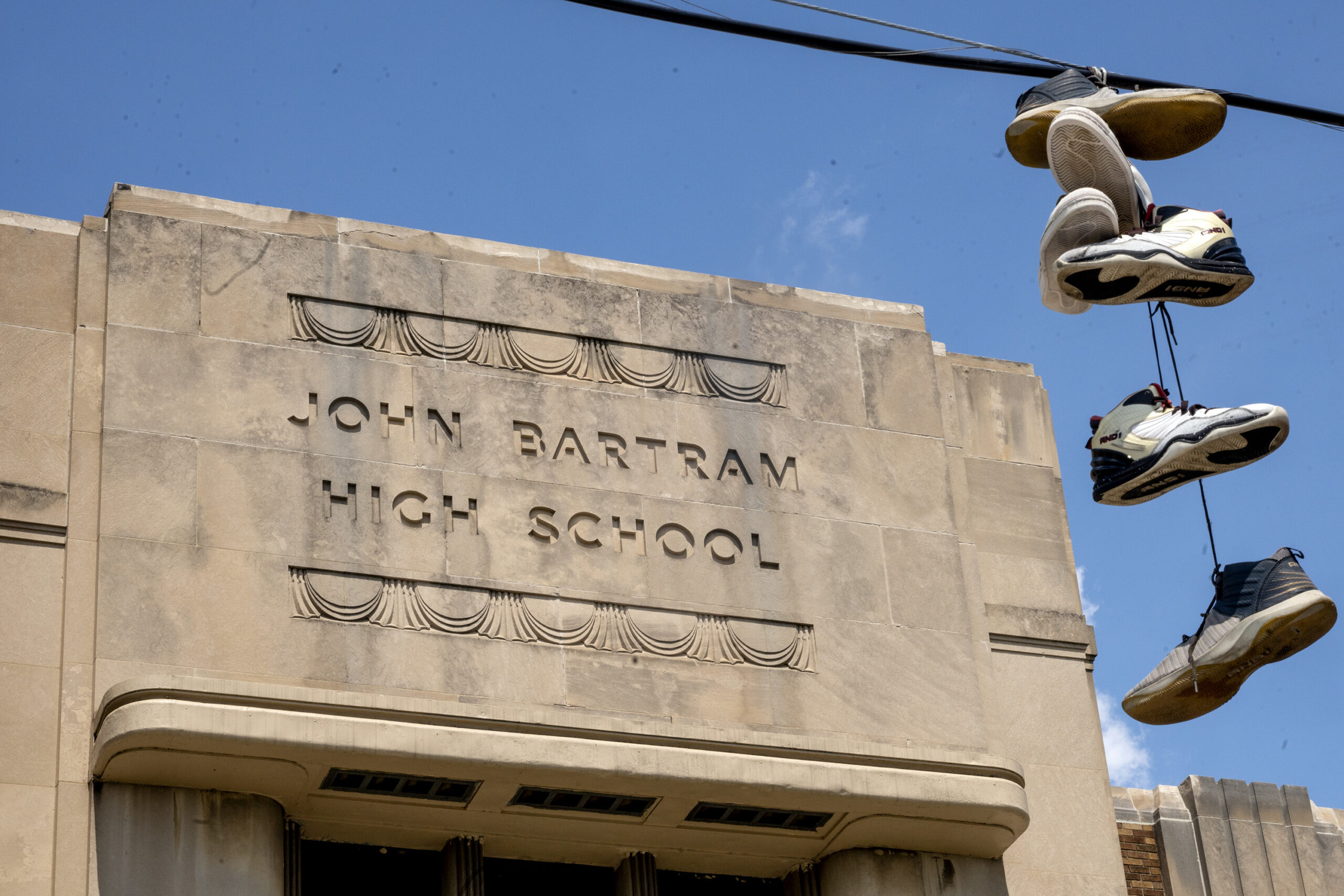

In recent years, a wave of labor actions has taken place across Penn and other local campuses. Temple University graduate workers went on strike for 42 days in 2023 during contract negotiations. Rutgers University educators, researchers, and clinicians walked off the job for a week that same year.

At Penn, the largest employer in Philadelphia, a wave of student-worker organizing in recent years has included resident assistants, graduate students, postdocs, and research associates, as well as training physicians in the University of Pennsylvania Health System.