Kelly Wyatt winced as a nurse unwrapped layers of gauze from her left leg, exposing the massive wound beneath.

Yellow and red and gray, weeping plasma and agonizingly painful at the slightest touch, it covered almost the entirety of the end of her leg — the site of the amputation she had undergone four years before.

Emergency room doctors at the time had warned her that if the drugs she was using didn’t kill her, her wounds would.

Now Wyatt is 14 months into recovery from an addiction to fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid, and xylazine, an animal tranquilizer never approved for human use. The emergence of xylazine, known as “tranq” on the streets, early in the decade marked the beginning of a dangerous new era for Philadelphians addicted to illicit opioids.

Tranq users developed skin lesions that became gaping wounds, though exactly how is still unclear. As the medical establishment scrambled to respond, amputations more than doubled among people addicted to opioids between 2019 and 2022.

Wyatt, 52, is among hundreds of Philadelphians facing lifelong medical needs from tranq, as the latest wave of the area’s drug crisis has seen a rapidly evolving succession of veterinary and industrial chemicals compound the dangers of the powerful opioids being sold on the streets.

Some have become regular patients in burn units and wound care clinics at area hospitals, among the only places capable of treating severe tranq injuries.

As part of its ongoing coverage of the area’s drug crisis, The Inquirer followed Wyatt for more than a year as she went through early recovery and worked with doctors to heal her wound.

Wyatt initially shrugged when the small sores had emerged on her legs, only to watch them grow into massive abscesses, resulting in an amputation below her knee. Her ongoing tranq use prevented the wound on her left leg from healing properly. Even after recent months of sobriety and careful treatment, doctors are still warning her that they may have to amputate more of her leg.

But Wyatt’s tranq wounds go still deeper.

Over the last several years, both of her sons had spiraled into addiction. By January, both of them were dead.

Spiraling into addiction

Several members of Wyatt’s family have struggled with addiction.

Wyatt experimented with drugs as a teenager, but was sober during her kids’ early childhoods. She didn’t drink alcohol, let alone seek out illicit drugs, after giving birth to her eldest son, Dakota, at 18. She raised two sons and a daughter in a neighborhood near Pennypack Park.

Her days had a familiar rhythm: packing lunches, picking the kids up from school, watching them play together at the local park. In her spare time, she dabbled in mixed-media art, designing the window displays at the downtown restaurant where she worked for years. One Philadelphia Flower Show-themed display had a working waterfall.

Her youngest, Tyler, was a happy child, grinning wide in every school picture and sharing inside jokes and a love for music with his brother. Dakota, more sensitive, had struggled with anxiety from an early age; Wyatt remembers him asking her at bedtime what the family would do if their house burned down in the night. But he could always make her laugh, and she and the boys would sing along to the same music in the car: ’90s alt-rock, Johnny Cash, the local hip-hop station.

In 1999, she divorced their father. A few years later, at 28, she took her first Percocet pill, an opioid painkiller approved for medical use that is widely abused as a street drug. She had just started working at a bar, and the long hours were wearing on her.

With the pills, “I could get more cleaning done, I could push my body more,” she said. “And it snowballed.”

She was not aware when her sons began using drugs themselves in their teenage years. “I didn’t know for a long, long time,” she said.

Afterward, Wyatt tried to help them seek treatment, even while her own drug use increased, she said.

But a series of traumatic life events resulted in all falling deeper into addiction together.

Wyatt’s ex-husband died following long-standing health issues, including diabetes.

Then Dakota, who drove a Zamboni at a local ice rink, was injured in an accident at work — losing the tips of his fingers while cleaning the machine. He had been using more opioids to deal with the pain.

Wyatt began buying drugs with him in Kensington, at the vast open-air drug market that is the epicenter of Philadelphia’s opioid crisis. “It was normalizing — I’m his mom and I’m with him in that crazy environment. I’m sure it made him feel like it was OK. And I regret that,” Wyatt said.

“I regret a lot of stuff. But that was the beginning.”

Tranq warning signs

It was the mid-2010s, and the drugs on the street were changing. The stronger synthetic opioid fentanyl was just emerging; dealers chanted “fetty-fetty-fetty” on the corners to draw in customers.

And then Wyatt began hearing talk of “tranq” getting mixed into the drug supply.

That was around the time that Dakota developed wounds on his arm, open sores that would not close. Wyatt found small wounds on her arms and legs — “like melon-ball scoops.”

One day, she saw a flier, handed out by health authorities in Kensington, warning that tranq can cause skin lesions.

“All of a sudden,” she recalled, “things made sense.”

But her addiction was so severe that she was afraid to stop using the fentanyl-tranq mix now prevalent in the illicit drug market. She fixated on avoiding xylazine’s severe withdrawal symptoms — chills, sweating, anxiety, and agitation — which don’t respond to traditional opioid withdrawal medications. She worried about seeking treatment with no guarantee of relief.

By the time Wyatt was admitted to a hospital in 2021, she was hallucinating from sepsis, a severe complication from an infection that can lead to organ failure, shock, and death.

When she woke up eight days later, a doctor told her she was at risk of having one leg amputated, and maybe both. “Please let me keep as much of my leg as possible,” she recalls begging a doctor who wanted to remove her entire leg.

“The doctor thought I should get the whole leg cut off. The other thing I could do was amputate below the knee, and then get tons of operations for the infection,” she said.

Her oldest son’s tranq wounds had also worsened. Dakota had wounds on his legs and an arm, which was eventually amputated later that year. He also suffered a heart infection linked to his drug use, and needed a valve replacement.

After a month in the hospital, he came home and continued using drugs.

He developed new lesions. Maggots ate at his rotting skin. Wyatt cleaned the bugs out of his wounds.

Wyatt tried bargaining with her son, promising they could get addiction treatment together. She offered to get him enough drugs that he wouldn’t enter withdrawal while waiting for care at the hospital. Sometimes, he managed to stay at the hospital for a few hours, but never longer.

“He was too embarrassed to go anywhere, he was too afraid to get clean, and he was too afraid to be sick. He told us he would rather die than go through withdrawal again,” she said. “A couple times, he asked me if I wanted to just shoot up and lay down and die with him.”

“‘I want to live,’” she recalls telling him, “‘and I don’t want to live without you.’”

Loss and recovery

One night in January 2024, Dakota was having trouble breathing and seemed to be hallucinating, speaking nonsense. He asked Wyatt to call an ambulance to the house.

Dakota died before the family reached the hospital. His cause of death was listed as drug intoxication.

Wyatt believes ongoing health issues from his wounds hastened his death. Her grief intensified her own drug use, leading to more xylazine wounds. The wound that had opened near her amputation grew worse.

A month after Dakota’s death, she entered drug treatment. After three months, she relapsed and overdosed on cocaine and fentanyl. Her first thought after waking up was to use again, but instead she chose rehab.

“I didn’t want to die,” Wyatt said. “I didn’t want to be in pain anymore.”

She arrived at the Behavioral Wellness Center at Girard in July 2024, hoping to enter outpatient rehab.

Instead, physicians recommended their inpatient clinic that could also treat her wounds, one of the few such facilities in Philadelphia.

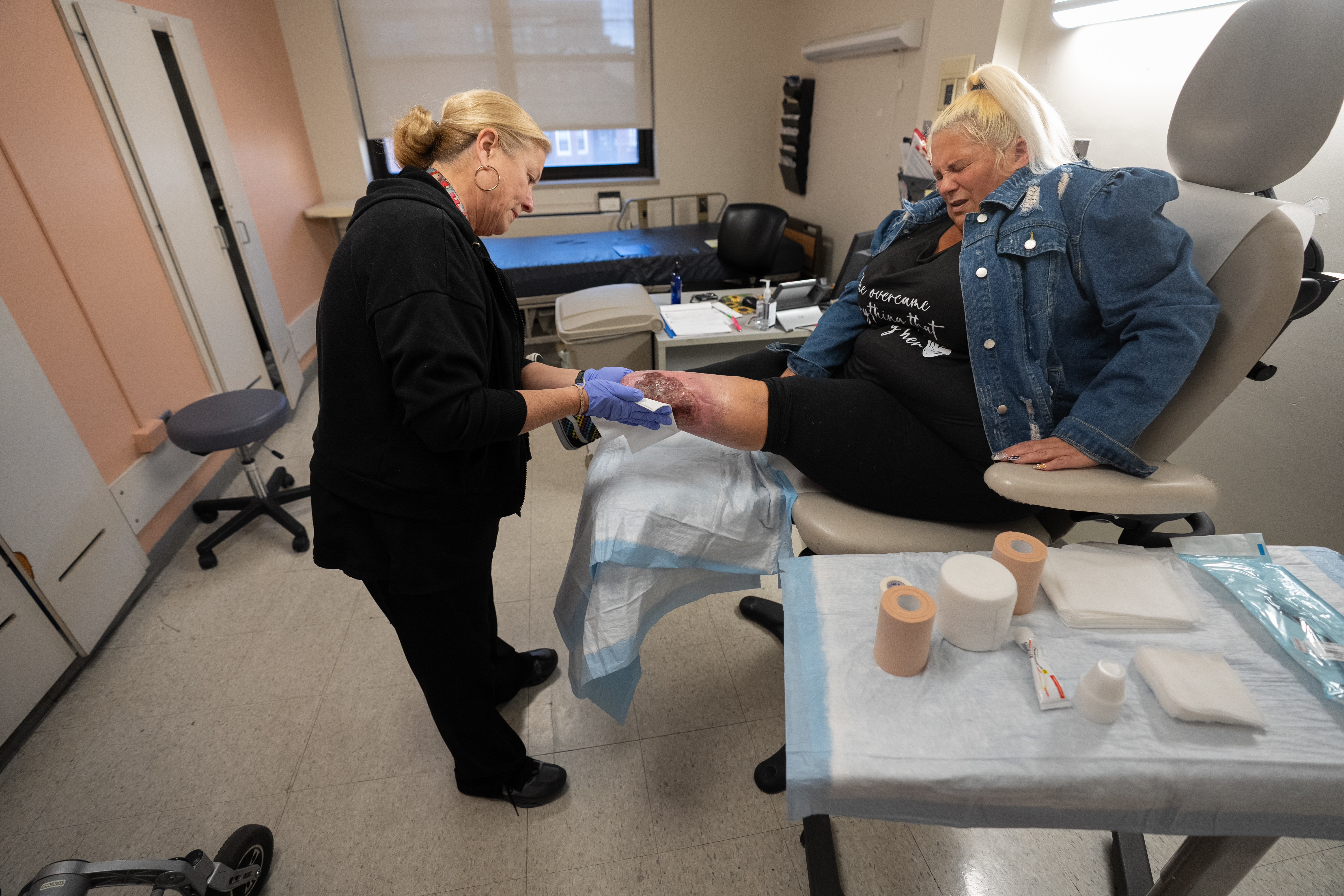

Wyatt was living there and undergoing treatment a month later, in August 2024, when she wheeled her motorized wheelchair into a clinic room and took deep breaths as nurses carefully peeled back layers of moisturized gauze on her left leg, cleaning the wound.

Still in the shaky early months of recovery, and needing to remain in inpatient rehab, she remained worried about Tyler, who was still using drugs.

“He was the primary caretaker of his brother. They would be in their room, getting high together. And now he’s just in that room by himself, day in and day out,” she said in an interview that summer.

“I kept saying, ‘I think I should go home to him.’ And everybody kept saying to me, ‘You have to work on yourself first. He’ll be fine,’” she later recalled.

“And then he wasn’t fine.”

A mother’s guilt

Wyatt was still in rehab in January 2025 when her partner, Randy Stewart, called. He hadn’t seen Tyler in hours and thought he might have left the family’s house.

Wyatt called several hospitals and then asked Randy to check the bathroom in the back of the house.

He found Tyler on the floor.

“I just thought, God, please no,” Wyatt said. “Not again. You can’t do this to me again.”

Tyler’s cause of death was also listed as “drug intoxication.”

He died at 27, a year and 10 days after his brother.

Wyatt is still wracked by guilt. Guilt that she used drugs with her sons. That she used drugs at all. That she wasn’t there when either of her boys died. That her daughter, who does not use drugs, stopped speaking to her. Sometimes, she dreams about her children and wakes up screaming.

As she continues treatment, Wyatt said, she hopes her story will help other families struggling with addiction, especially the realities of tranq use.

“Sometimes I’m embarrassed to talk about it. But I feel like I have to,” she said. “Because people need to know. If one person sees this and gets some medical care, gets any kind of help, I would be happy.”

Treating tranq’s wounds

For Wyatt, maintaining her recovery from addiction and caring for her wounds are full-time occupations that sometimes are in conflict.

Methadone, the opioid addiction treatment drug that has helped Wyatt curb cravings for more than a year, can be dispensed only at special clinics.

Wyatt’s clinic journey meant three hours a day on a bus where she couldn’t keep her leg elevated. The wound worsened until she was able to switch to a closer methadone clinic.

Wyatt relies on Stewart to help her move around her home, where the only bathroom that she can access is the one where Tyler died.

“Cleaning, taking care of me, changing my wound dressings, talking about my sons — he calms me down. It’s been a lot, and he’s really done a lot,” she said.

Once a week, Wyatt travels to Jefferson Einstein Philadelphia Hospital’s Center for Wound Healing for wound care.

At a recent appointment, nurse practitioner Danielle Curran scraped away infected skin, measured the wounds, cleaned and re-bandaged her lesion.

In between office visits, nurses also go to her home to clean and re-bandage her wound twice weekly. Several times this year, Wyatt has undergone debridement surgery to remove more damaged skin under anesthesia.

If the treatments manage to shrink her wound, Curran said, Wyatt could try a skin graft and eventually receive a prosthetic leg that could help her get around more easily.

Curran has treated about 20 xylazine patients at the clinic over the last few years. About 10, including Wyatt, are still getting regular care. Others have relapsed and returned to the streets. Several have died of overdoses.

She is relieved that, as Philadelphia’s opioid crisis continues to evolve, tranq is becoming less prevalent. But it has been replaced in street drugs by another animal tranquilizer, medetomidine, which does not appear to cause flesh wounds but, rather, agonizing withdrawal symptoms. Skin lesions among opioid users have decreased in the last year.

Yet Curran still insists on seeing patients like Wyatt with xylazine wounds weekly, trying to help them through their injuries and hopefully their recovery, too. “I like to be another person holding them accountable, to stay on the path. We try to give them that support.”

Sometimes, that support means simply reminding Wyatt how far she has come in the four years since the amputation, and now 14 months of sobriety.

At a recent appointment, after carefully scraping dead skin away from Wyatt’s leg with a small curette, Curran walked through her next steps: A disinfecting gel to keep bacteria out of the wound. A course of antibiotics to avoid infection. Another debridement surgery, in a few weeks.

“As a rule of thumb,” Curran told a reporter, “it’s very hard to give timelines for wound care, because of all the things that could possibly go wrong. A wound this size, though? It could take years.”

Wyatt began to cry. “It’s already been four years,” she said.

Curran turned to her. “You’ve made so much progress,” she said gently. “Give yourself time.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to clarify the name of the Jefferson Health clinic where Kelly Wyatt received wound care.