New Jersey lawmakers on Monday approved a bill that would make it easier for development projects in Camden to qualify for hundreds of millions of dollars in tax credits.

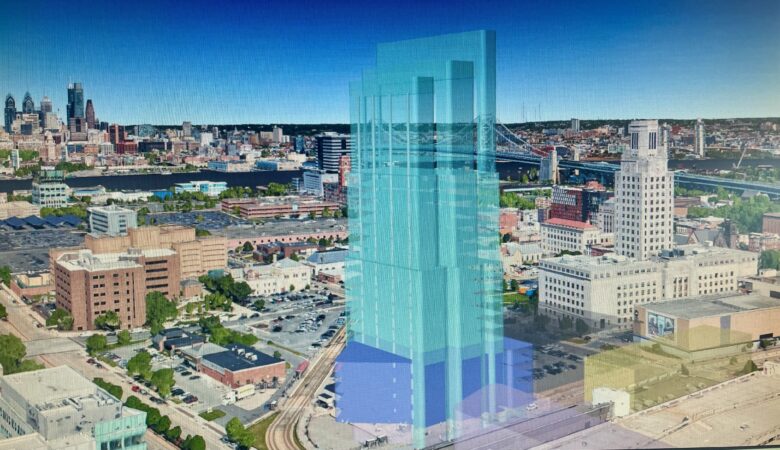

That could be a boon to the Beacon Building — a planned 25-story office tower downtown whose backers have said they intend to seek state incentives — among other projects, according to the bill’s supporters.

Under current law, most commercial real estate developers must show their projects would generate more dollars in economic activity than they would receive in subsidies in order to qualify for tax credits under New Jersey’s gap-financing program, known as Aspire.

The new legislation — which was introduced late last month and approved by the Democratic-led Legislature days before Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy is to leave office — would exempt certain projects from the program’s so-called net benefit test.

Lawmakers on Monday also passed a bill increasing the cap on the size of the Aspire tax-credit program from $11.5 billion to $14 billion and authorized $300 million in tax breaks to renovate the Prudential Center in Newark, home of the New Jersey Devils hockey franchise. The team is owned by Harris Blitzer Sports & Entertainment, which also owns the Philadelphia 76ers.

‘Competitive market’

Supporters of the Camden bill, A6298/S5025, said it would make South Jersey more competitive in the Philadelphia market, while critics contended it would weaken a provision of a 2020 economic development law signed by Murphy that was intended to ensure fiscal prudence.

The test has impeded big projects in South Jersey, said Assembly Majority Leader Louis Greenwald (D., Camden), a sponsor of the bill. Since the law was signed, the region hasn’t attracted a single “transformative project” — a designation in the Aspire program for developments that have a total cost of $150 million and are eligible for up to $400 million in incentives over 10 years, Greenwald said.

“We started to ask people, what’s the barrier?” he said. “And when you look at the competitive market of what [developers] can get in Philadelphia or Pennsylvania compared to other areas in the state that don’t have to compete with that, that net operating loss test, that net benefits test, is a barrier.”

The legislation was not drafted with a specific project in mind, Greenwald said, but he acknowledged that one that might benefit is Beacon, which would feature 500,000 square feet of office space.

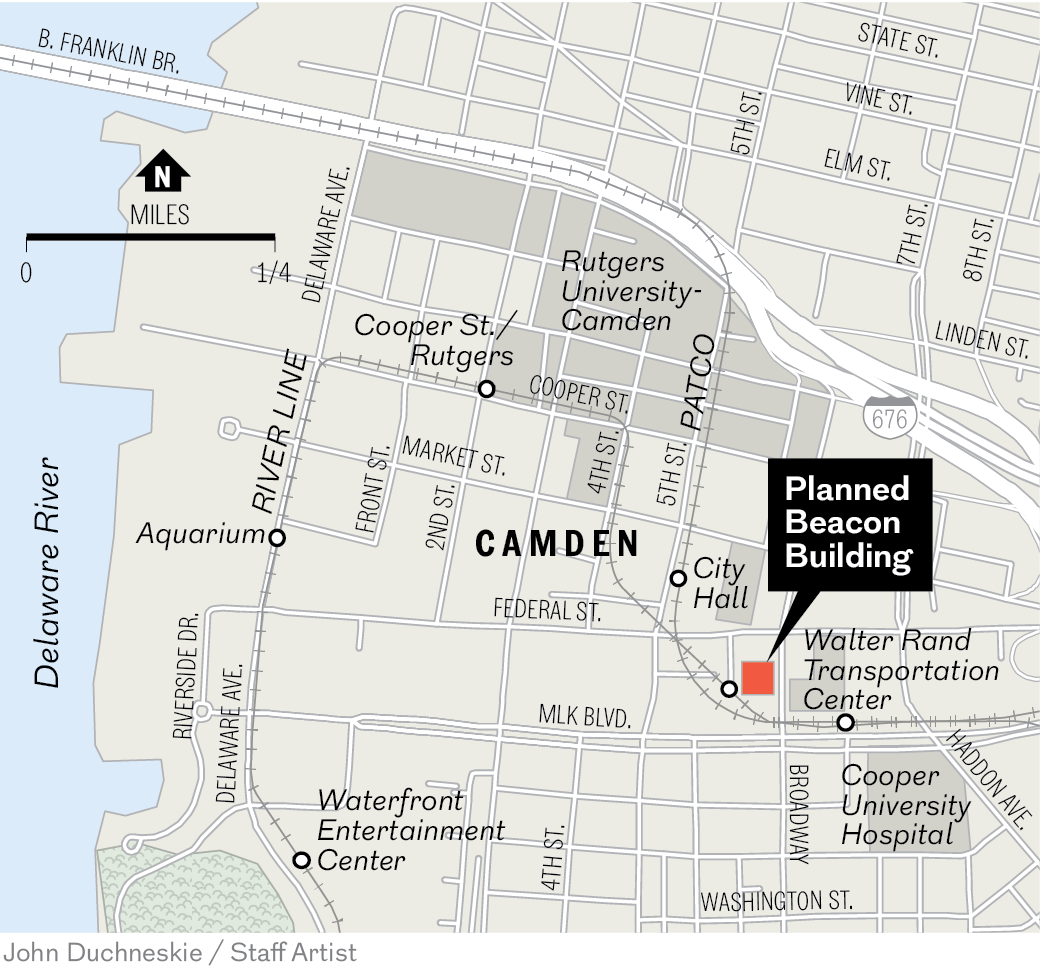

Developer Gilbane is leading the project with the Camden County Improvement Authority at a vacant site on the northwest corner of Broadway and Martin Luther King Boulevard across the street from the Walter Rand Transportation Center and Cooper University Hospital.

“The goal is to attract projects, maybe like Beacon Tower, to capitalize off of the growth that we’ve seen in Camden city,” Greenwald said.

Any project seeking Aspire subsidies must apply to the Economic Development Authority.

Camden County officials have said they expect tenants to include Cooper University Health Care, which has said it needs additional office space to accommodate its $3 billion expansion. They also hope to entice civil courts to relocate there.

County Commissioner Jeff Nash said last year that tenants had yet to commit, in part because the development team was still working on an application for Aspire tax credits.

The incentives will help determine rent, he told the Cherry Hill Sun. The land is owned by the Camden Parking Authority, and Nash has said officials are still trying to determine who will own the site and the building going forward, according to Real Estate NJ.

County spokesperson Dan Keashen said that those talks remain ongoing and that the improvement authority may issue a request for proposals for a new developer. Gilbane, the current master developer, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Wendy Marano, a spokesperson for Cooper University Health Care, said she didn’t have an immediate answer to a question about whether the hospital network planned to obtain an equity stake in the development.

In 2014 the state awarded $40 million in tax credits to incentivize Cooper Health’s relocation of suburban office jobs to Camden, and Cooper later bought a stake in the development.

The possible new state investment in Camden comes after Murphy’s administration separately allocated $250 million to renovate the state-owned Rand center — which serves two dozen NJ Transit bus lines and the River Line, and includes PATCO’s Broadway station.

Construction on the transit center is expected to begin soon, according to county officials. While that renovation is underway, the Beacon site will serve as a temporary bus shelter, Keashen said, adding that possible construction on an office tower is still years away.

Fast track

Critics of the bill said that it was rushed through the Legislature with minimal public input and outside the normal budget process, and that it appeared to be designed to benefit specific projects. The bill passed the Assembly, 48-25, and the Senate, 24-14. It now heads to Murphy’s desk. The governor’s second term ends on Jan. 20, when he is to be succeeded by fellow Democrat Mikie Sherrill.

The legislation applies to redevelopment projects located in a “government-restricted municipality” — language included in the Aspire program’s statute — “which municipality is also designated as the county seat of a county of the second class.” The project must also be located in “close proximity” to a “multimodal transportation hub,” an institution of higher education, and a licensed healthcare facility that “serves underrepresented populations.”

“I say to you that there’s going to be one project that fits all those criteria,” Assemblyman Jay Webber (R., Morris) said on the floor of the chamber during debate Monday.

“The net benefits test was put in as an accountability measure to make sure these projects were at least by some measure benefiting the taxpayer,” Webber added in an interview.

“And now apparently one or more projects can’t meet that test,” he said. “And so rather than stick to the rules that they agreed to and pull the credits, they’re going to change the rules, lower the bar so that somebody can step over it. It’s wrong.”

Greenwald said the legislation has “nothing to do with [Beacon] in particular,” adding that he hopes it is one of many projects that could benefit. Possible developments in Trenton and New Brunswick could also qualify for incentives under the bill, he said.

The net benefit test

The test relies on economic modeling based on data such as projected jobs and wages. Under current law, most commercial projects seeking Aspire credits must demonstrate a minimum net benefit to New Jersey of 185% of the tax credit award — meaning, for instance, an applicant that receives $100 million in credits must generate $185 million in economic activity.

The credits can be sold to the state Treasury Department for 85 cents on the dollar.

Projects located in “government-restricted municipalities” — a half-dozen cities, including Camden, selected by the Legislature — already face a lower threshold of 150%, according to the state Economic Development Authority.

Some projects, including residential and certain healthcare centers, are exempt from the net benefit test.

The test was strengthened in the Economic Recovery Act of 2020, signed by Murphy, because “we saw in previous iterations of the tax credit program that if the guardrails weren’t strong enough … then companies could simply not meet the test, or, you know, not follow through on their promises, and nonetheless collect the funds,” said Peter Chen, senior policy analyst at New Jersey Policy Perspective, a liberal-leaning think tank.

The 2020 law changed that, he said. “It’s one of the most important guardrails of the entire corporate tax credit program,” Chen said in an interview last week. “So exempting any project from the net benefit test requires a pretty large, pretty strong reason for doing so, and in this case, no reason was given.”

Criminal case

The renewed push for tax credits in South Jersey comes as a criminal case involving an earlier round of corporate subsidies continues to play out in court.

Democratic power broker George E. Norcross III — founder of a Camden-based insurance brokerage and chairman of Cooper Health — and five codefendants were indicted in 2024 on racketeering charges related to development projects on the city’s waterfront.

A judge dismissed the charges last year, and the state Attorney General’s Office is appealing the decision. Norcross has denied wrongdoing. He and his allies say state incentives have helped revitalize the city.

During his floor speech on Monday, Webber alluded to “incredible allegations of corruption” in the earlier economic development program and noted that Murphy had previously championed reform of the system.

The governor’s spokesperson, Tyler Jones, declined to comment on pending legislation.