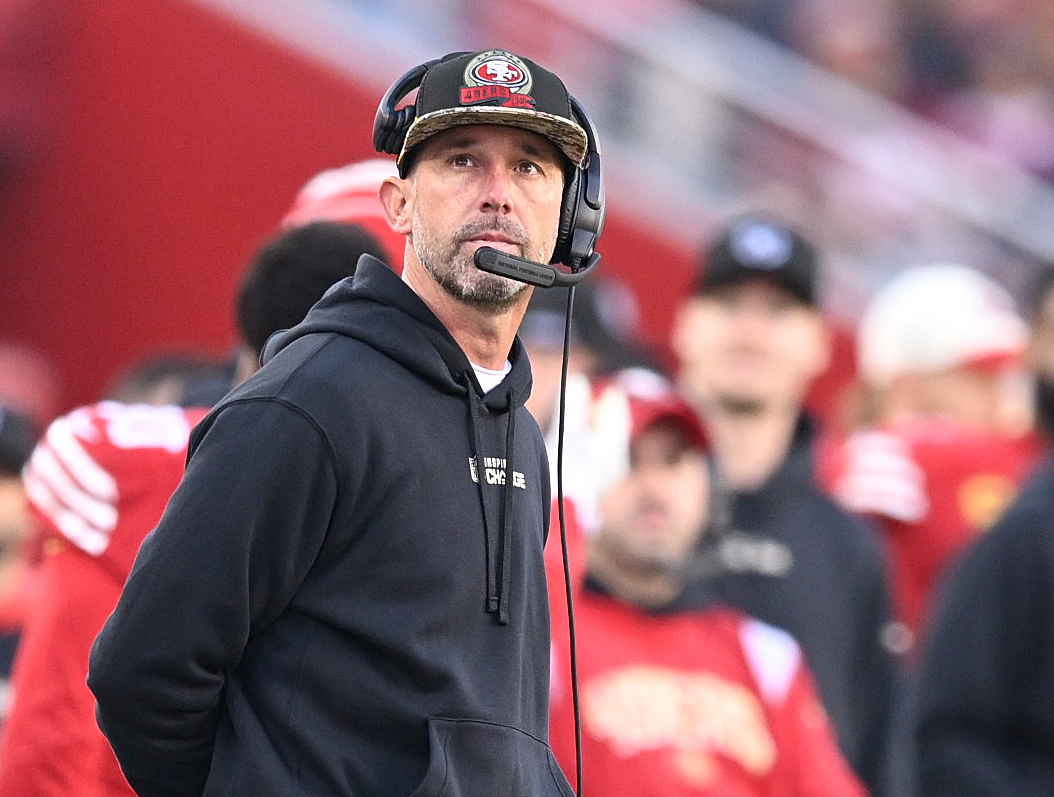

The play that encapsulated everything the Eagles offense wasn’t this season was a play that they themselves didn’t even run. First snap of the fourth quarter Sunday night for the San Francisco 49ers, first-and-10 from the Eagles’ 29-yard line, and there was Kyle Shanahan, calling a double-wing reverse pass that made one of the NFL’s best defenses look like a bunch of suckers. Brock Purdy handed the football to Skyy Moore, who pitched it to Jauan Jennings, who rainbowed a pass toward the end zone to Christian McCaffrey, who didn’t have an Eagles player within 5 yards of him.

A six-point Eagles lead suddenly was a one-point deficit. And though that touchdown technically wasn’t the winning score in the 49ers’ 23-19 wild-card victory, it was the perfect symbol for the difference between a team that played like it had nothing to lose and a team that played like it was fearful of taking the slightest of chances.

From Nick Sirianni to Kevin Patullo to Jalen Hurts, the Eagles spent too much of this season acting as if being daring was taboo for them. Sirianni preached the importance of minimizing turnovers, citing the Eagles’ marvelous record during his tenure as head coach when they protected the football better than their opponents. But it turned out that a Super Bowl champion cannot defend its title on caution alone. The 49ers committed two turnovers. The Eagles didn’t commit any. And the final score was the final score.

In the locker room afterward, player after player used the same word as the cause of the Eagles’ struggles during the regular season and their quick exit from the postseason: execution. “If there are multiple players saying that,” tackle Jordan Mailata asked, “why don’t you believe us?” Good question. Here’s why: It’s a familiar, sometimes default way of thinking among elite athletes: It doesn’t matter what the coach calls. It doesn’t matter if my opponent knows what’s coming. If I do exactly what I’m supposed to do exactly when I’m supposed to do it, nothing can stop me, and nothing can stop us.

“I don’t think we were playing conservatively,” running back Saquon Barkley said. “I think it comes down to execution. A lot of the same calls we have — I know it was a new offensive coordinator and new guys, but we kind of stuck with the same script, to be honest, of what we did last year. It’s easy to say that when you’re not making the plays. … If we’re making the plays, no one is going to say we’re being conservative.”

The Eagles could get away with following that mantra last season. Their offensive line was the best in the league, and they shifted midseason from having Jalen Hurts throw 30-plus passes a game to giving the ball to Barkley and counting on him for consistent yardage and big plays. But, as Barkley acknowledged, they returned this season with pretty much the same offense — after the other 31 teams had an offseason to study what the Eagles had done and come up with ways to neutralize it.

“If they call inside zone and we call inside zone and they run it better than us, they just ran it better than us,” Barkley said. “They executed better than us. That’s just my mindset. Maybe I’m wrong.”

He is. There rarely was any surprise to the Eagles’ attack this season, rarely any moments when A.J. Brown or DeVonta Smith was running free and alone down the field, when Barkley wasn’t dodging defenders in the backfield, when anything looked easy for them. When everyone in the stadium knows you’re likely to call a particular play in a particular situation, yes, you had better be perfect in every aspect of that sequence. But when you catch a defense off guard — as Shanahan did on Jennings’ pass — your execution can be less than ideal, and the play will still work.

Look at Sunday: Barkley had 15 carries in the first half and 11 in the second. He had 71 yards in the first half and 35 in the second; after halftime, the 49ers started sending more players toward the line of scrimmage just before Hurts took the snap. The proper countermove would have been to throw the ball downfield more often, but the Eagles were reluctant to court such risk. It doesn’t much matter whether Patullo couldn’t scheme up such plays or whether, even if Patullo had opened up the offense, Hurts would have held the ball anyway. The result was the same. They settled for what was safe.

“I think that’s always the go-to. … People think you take your foot off the gas,” Sirianni said. “We didn’t create enough explosives. They did.”

To the end, the head coach struggled to see the connection between his conservatism and the problems that plagued his offense. No Super Bowl appearance, no title defense, not even a spot in the playoffs’ second round. Over 18 games, this team wrote its own epitaph.

The 2025 Eagles: They played not to lose. Which is why they did.