Should last week’s election results make Brian Fitzpatrick nervous?

Bucks County Democrats think so.

The Republican lawmaker has been like Teflon in the 1st Congressional District, which includes all of Bucks County and a sliver of Montgomery County. He persistently outperforms the rest of his party and has survived blue wave after blue wave. First elected in 2016, he has remained the last Republican representing the Philadelphia suburbs in the U.S. House.

But Democrats pulled something off this year that they hadn’t done in recent memory. They won each countywide office by around 10 percentage points — the largest win margin in a decade — and for the first time installed a Democrat, Joe Khan, as the county’s next top prosecutor.

Now they are looking to next year, hopeful that County Commissioner Bob Harvie, the likely Democratic nominee, succeeds where Fitzpatrick’s past challengers have failed.

“This year was unprecedented, and sitting here a year before the midterm, you have to believe that next year is going to be unprecedented as well,” State Sen. Steve Santarsiero, who is also the county party’s chair, said Wednesday.

Eli Cousin, a spokesperson for the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, predicted a “perfect storm brewing for Democrats” to beat Fitzpatrick. “He and Trump’s Republican Party are deeply underwater with Bucks County voters; he has failed to do anything to address rising costs, and we will have a political juggernaut in Gov. Josh Shapiro at the top of the ticket,” Cousin said.

There are several reasons Democrats may be exhibiting some premature confidence: Despite a spike in turnout for an off-year election, far fewer voters turn out in such elections than do in midterms. Fitzpatrick is extremely well-known in Bucks, where his late brother served before he was elected to the seat. He has won each of his last three elections by double digits.

Just last year, President Donald Trump narrowly won Bucks County, becoming the first Republican presidential candidate to do so since the 1980s, and Republicans overtook Democrats in voter registrations last year.

But Tuesday was a sizable pendulum swing in the bellwether. Some of the communities, like Bensalem, that drove Trump’s victory flipped back to blue.

The last time Democrats had won a sheriff’s race in the county was 2017, a year after Trump was elected the first time. That year, Democrats won by smaller margins, and a Republican incumbent easily won reelection as district attorney. The following year, Fitzpatrick came the closest he has yet to losing a race, but still won his seat by 3 percentage points.

This year’s landslide, Democrats say, is a warning sign.

“There were Democratic surges in every place that there’s a competitive congressional seat, and that should be scaring the s— out of national Republicans,” said Democratic strategist Brendan McPhilips, who managed Democratic Sen. John Fetterman’s campaign in the state and worked on both of the last Democratic presidential campaigns here.

“The Bucks County seat has always been the toughest, but it’s certainly on the table, and there’s a lot there for Bob Harvie to harness and take advantage of.”

Harvie, a high school teacher-turned-politician, leapt on the results of the election hours after races were called, putting out a statement saying, “There is undeniable hunger for change in Bucks County.”

“The mood of the country certainly is different,” Harvie said in an interview with The Inquirer on Thursday. “What you’re seeing is definitely a referendum.”

Lack of GOP concern

But Republicans don’t appear worried.

Jim Worthington, a Trump megadonor who is deeply involved in Bucks County politics, attributes GOP losses this year to a failure in mail and in-person turnout. Fitzpatrick, he said, has a track record of running robust mail voting campaigns and separating himself from the county party apparatus.

“He’s not vulnerable,” Worthington said. “No matter who they run against him, they’re going to have their hands full.”

Heather Roberts, a spokesperson for Fitzpatrick’s campaign, noted that the lawmaker won his last election by 13 points with strong support from independent voters in 2024 — a year after Democrats performed well in the county in another off-year election. She dismissed the notion that Harvie would present a serious challenge, contending the commissioner “has no money and no message” for his campaign.

Fitzpatrick is also a prolific fundraiser. He brought in $886,049 last quarter, a large amount even for an incumbent, leading Harvie, who raised $217,745.

“Bob Harvie’s not going to win this race,” said Chris Pack, spokesperson for the Defending America PAC, which is supporting Fitzpatrick. “He has no money. He’s had two dismal fundraising quarters in a row. That’s problematic.”

Pack noted Harvie’s own internal poll, reviewed by The Inquirer, showed 57% of voters were unsure how they felt about him.

“An off-off-year election is not the same as a midterm election,” Pack said, adding he thinks Fitzpatrick’s ranking as the most bipartisan member of Congress will continue to serve him well in Bucks County.

“He’s obviously had well-documented breaks on policy with the Republican caucus in D.C., so for Bob Harvie to try to say Brian Fitzpatrick is super far right, no one’s gonna buy it,” Pack said. “They haven’t bought it every single election.”

On fundraising, Harvie said he had brought in big fundraising hauls for both of his commissioner races, and said he would have the money he needed to compete.

Of the four GOP-held House districts Democrats are targeting next year in the state, Fitzpatrick’s seat is by far the safest. That raises the question: How much money and attention are Democrats willing to invest in Pennsylvania?

“Who’s the most vulnerable?” asked Chris Nicholas, a GOP consultant who grew up in Bucks County. The other three — U.S. Rep. Scott Perry and freshman U.S. Reps. Rob Bresnahan, in the Northeast, and Ryan Mackenzie, in the Lehigh Valley — won by extremely narrow margins last year. “If you’re ranking the four races, you have Rob Bresnahan at the top and Fitzpatrick at the bottom,” Nicholas said.

National Democrats seldom invest as much to try to beat Fitzpatrick as they say they will, Nicholas said. And he pointed to 2018, a huge year for Democrats, when they had a candidate in Scott Wallace who was very well-funded, albeit far less known than Harvie, and still came up short.

Democrats see Harvie as the best shot they have had — a twice-elected commissioner, with name ID from Lower Bucks County, home to many of the district’s swing voters. And the 1st District is one of just three in the country that is held by a Republican member of Congress where Vice President Kamala Harris won last year.

And then there’s Shapiro, who Democrats think will give a boost to candidates like Harvie as he runs for reelection next year. Shapiro won the district by 20 points in 2022.

Following the playbook used by successful candidates this year, Democrats are likely to argue to voters that Fitzpatrick has done little to push back on Trump — while placing cost-of-living concerns at the feet of the Republican Party.

“A lot of people are, you know, upset with where we are as a nation,” Harvie said. “They grew up expecting that if you worked hard and played by the rules, you’d be able to have all the things you needed and have a good life. And that’s not happening for them.”

The Trump effect

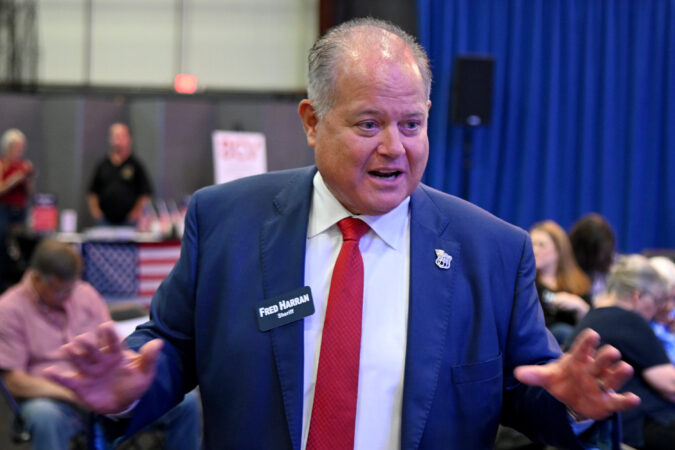

Democrats won races in Bucks County, and across the country, this year by tying their opponents to Trump — a tactic that was especially effective in ousting Republican Sheriff Fred Harran, who partnered his office with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. In recent cycles, that strategy has not worked against Fitzpatrick.

“The big thing Democrats throw against Republicans is you’re part and parcel of Trump and MAGA, and Fitzpatrick voted against Trump,” Nicholas said.

Over nearly 10 years in Congress, Fitzpatrick has been a rare Republican who pushes back on Trump, though often subtly. Fitzpatrick, who cochairs the bipartisan Problem Solvers Caucus, was the lone Pennsylvania Republican to confirm former President Joe Biden’s electoral victory in 2020. A former FBI agent who spent a stint stationed in Ukraine, he is among the strongest voices of support for Ukraine in Congress, consistently pushing the administration to do more to aid the country as it resists a yearslong Russian invasion.

Fitzpatrick was also one of just two House Republicans to vote against Trump’s signature domestic policy package, which passed in July. He voted for an earlier version that passed the House by just one vote, which Democrats often bring up to claim Fitzpatrick defies his party only when it has no detrimental impact.

“He’s good at principled stances that ultimately do nothing,” said Tim Persico, an adviser with the Harvie campaign. “That is what has allowed him to defy gravity in the previous cycles. … Now the economy is doing badly. … People feel worse about everything, and Fitzpatrick isn’t doing anything to help with that. I think it makes it harder to defy gravity.”

Trump has endorsed every Republican running for reelection in Pennsylvania next year except Fitzpatrick. While the Bucks County lawmaker has avoided direct criticism of the president, in an appearance in Pittsburgh over the summer, Trump characterized the “no” vote on the domestic bill as a betrayal.

Fitzpatrick has faced more conservative primary challengers in the past, but no names have surfaced so far this cycle, a sign that even the more MAGA-aligned may see him as their best chance to hold onto the purple district.

Keeping his distance from Trump, and limiting Democrats’ opportunities to tie the two together, may remain Fitzpatrick’s best path forward.

“Anybody who wants to align themselves with an agenda of chaos and corruption and cruelty ought to be worried,” said Khan, Bucks County’s new district attorney-elect.

This suburban content is produced with support from the Leslie Miller and Richard Worley Foundation and The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Editorial content is created independently of the project donors. Gifts to support The Inquirer’s high-impact journalism can be made at inquirer.com/donate. A list of Lenfest Institute donors can be found at lenfestinstitute.org/supporters.