The Philadelphia Housing Authority embarked on a strategy last year unlike anything it has done before.

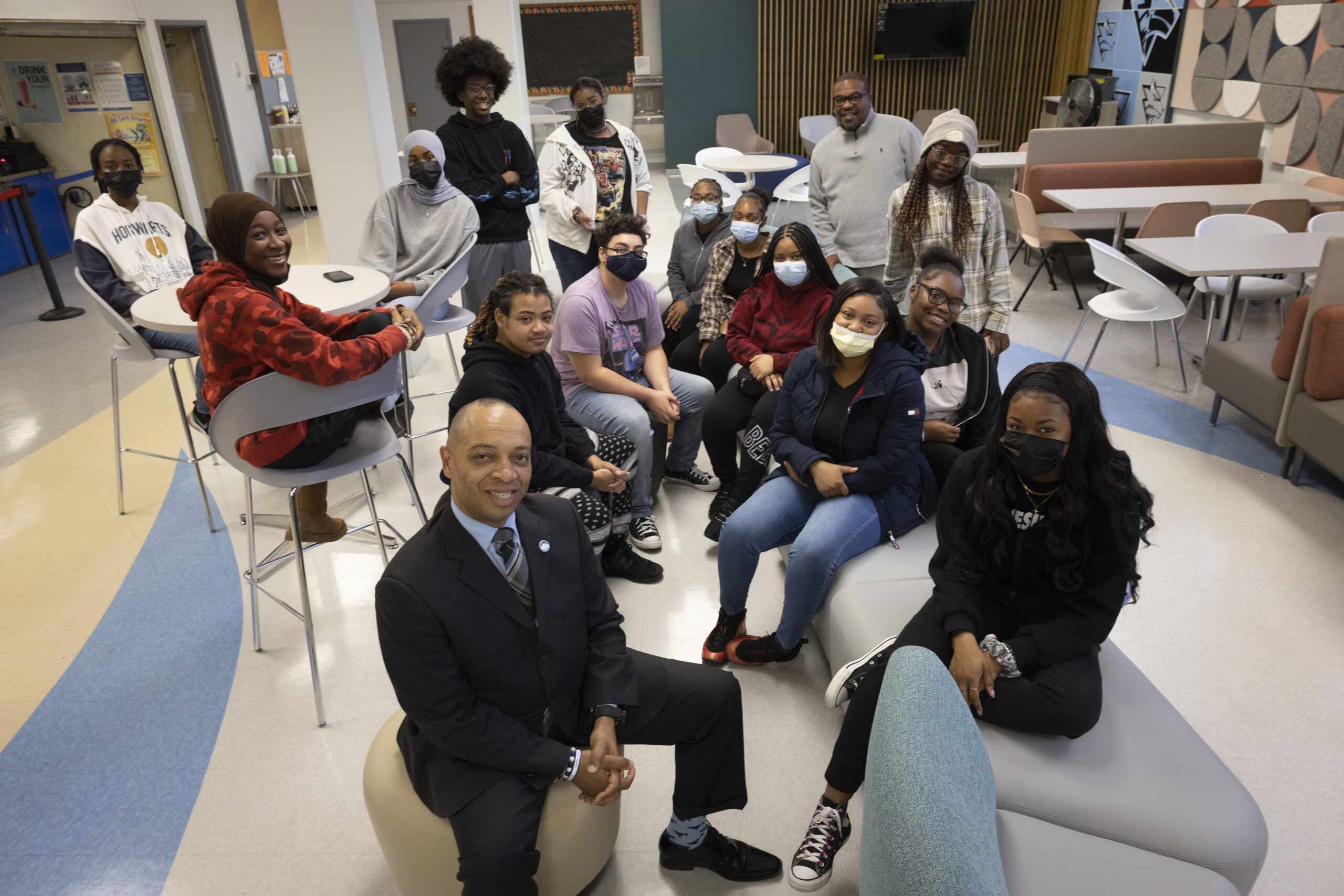

The agency is known as the largest affordable housing provider in the city. But in 2025, under the leadership of CEO Kelvin Jeremiah, it began buying struggling private-sector apartment buildings all over the city to expand the affordable housing supply.

Over the last 14 months, the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) has spent $280.6 million to acquire 17 multifamily properties, totaling 1,515 units. Some have been student apartments or largely empty new buildings. But most have been full of tenants paying market-rate rents, ranging from $1,106 to $2,323.

That’s a new demographic for PHA, whose renter base often makes less than $30,000 a year.

PHA plans to fill these buildings with Section 8 voucher holders, who often have a difficult time finding rentals in higher income areas.

“It’s part of the strategy … to give residents the broadest possible options in terms of their housing choice and one that is not limited to particular neighborhoods,” Jeremiah said.

In an innovation, the agency intends to keep renting some units in the newly acquired buildings at the market rate, using the income to support operating expenses.

The first PHA purchase in 2025 was The Dane, a 233-unit building in Wynnefield. It now houses some tenants paying market-rate rents and others using government subsidies.

Last year, several tenants contacted The Inquirer with concerns about what they described as a rocky transition to PHA ownership. Since then, interviews with 18 tenants at The Dane have laid out challenges within PHA’s new model — and the potential difficulty of retaining renters with options elsewhere.

Eighty-six people have moved out of The Dane over the last year. That’s about half the original occupants as the building was only 75% occupied when purchased.

The overwhelming majority of tenants interviewed by The Inquirer said PHA is a better landlord than the previous owner, Cross Properties. But most have moved out or are planning to.

“The management staff that are there now are better than what we had, but they’re still pretty mediocre,” said one resident, who, like many of the tenants, asked that their name be withheld to preserve relations in the building.

“Everybody’s very polite; everybody’s very cordial, but it’s only maybe one or two maintenance people,” this multiyear resident said. “The trash pileup is very bad right now … I plan to move elsewhere.”

Jeremiah noted that most of the properties PHA acquired have not experienced the kind of turnover that The Dane has seen. The building is now almost completely occupied with both market-rate and subsidized tenants, said a PHA spokesperson.

He said some tenants moved out after the agency began collecting rent again. Many had been withholding payments to Cross, which lacked a rental license at the end of its tenure.

It’s possible that the turnover at The Dane is largely the result of a difficult property transfer from a troubled previous owner. (Cross Properties is no longer in business.) In that case, the tenant exodus may not be a predictor for PHA’s larger ambitions.

But given the skepticism PHA faces in many neighborhoods, outside observers say, the agency’s new expansion strategy faces high expectations to get everything right.

“PHA is under a tremendous amount of pressure,” said Akira Rodriguez, a professor of housing policy at the University of Pennsylvania. “There’s going to be experiences that are uneven for tenants as they navigate this new model of housing provision … [and The Dane] is a really high visibility example.”

A long troubled apartment building

In November 2024, residents of The Dane were fed up. Their hot water wasn’t working — again — in apartments where many households paid over $2,000 a month in rent.

“The owner [Cross Properties] was not the best,” said Akeesha Washington, who has lived in The Dane since 2020. “He just didn’t maintain the building. Over the years, you saw the amenities dwindle.”

Cross Properties acquired the building in 2016 when it was the Penn Wynn House and converted the rent-subsidized building into market-rate apartments.

When Washington moved in, she was impressed. The staff were kind to her in 2020 when she contracted COVID-19. They coordinated care with Washington’s mother so she had access to medication without infecting anyone.

“It was a really nice community. It’s luxury in the 19131 section, where not everyone feels like they can afford it,” said Washington, who loves the diversity of the tenants, which included university students, working-class residents, and doctors and lawyers.

“You had so many layers of people living and coexisting in this building,” Washington recalled. Rents ranged from $1,100 for a studio to $2,200 for a two-bedroom unit with two bathrooms.

But by 2024, most tenants said, building management had fallen off. Trash wasn’t picked up regularly; lawns went unmowed and snow unshoveled, and basic amenities like the parking garage door often didn’t work.

Shortly after another hot water outage, tenants got news in late 2024 that Cross Properties was out.

“When residents heard it was being acquired, we were excited because we won’t have to deal with not having hot water, especially during the holidays,” Washington said.

New management, new problems

When PHA purchased The Dane, the building had many unresolved issues, said Tonya Looney, who worked for Cross Properties as the building’s manager. And she said there was scarce planning for the details of the transfer.

“To be fair, this is something new and I understand from a real estate professional’s perspective that there’s going to be hiccups,” said Looney, who stopped working at The Dane last May, although she still manages 15 apartments for long-term corporate stays in the building.

Looney is in a legal dispute with PHA, which says she owes substantial back rent. “We do not intend to renew the leases that she has in her name,” Jeremiah said. “I do not think she is a good arbiter of the facts in this case.”

Both Jeremiah and Looney say that after the sale closed, Cross Properties shut down the operating software, cutting off tenants’ ability to pay rent online, see their rental histories, and submit maintenance requests.

“We had 200 people with no way to log in to pay their rent, no way to submit a maintenance ticket, no idea who to talk to about any issues at the building unless they came downstairs to see what’s going on,” Looney said. “Needless to say, it was chaotic.”

For much of 2025, residents had to pay with checks, which sometimes went uncashed, according to Washington and Looney.

Jeremiah says that Cross Properties’ owner asked PHA to pay to access the former tenant management system, although PHA eventually figured out how to get the records.

Despite the chaotic transition, many tenants said PHA’s ownership brought improvements from previous conditions, especially after Maryland-based HH Redstone was brought in to operate The Dane in August. (That’s when online payments, for example, started working again.)

“HH Redstone is doing what they can, and I’ve re-signed my lease for one year because I am willing to see what change they can continue to make,” said another tenant who asked not to be named.

Why tenants are leaving, even with improved conditions

Other tenants say property services continue to suffer.

Trash pickup is still persistently late, several tenants said. Pest outbreaks such as bedbug, mouse, and cockroach infestations flare up, which is new in the building, according to Washington and two other tenants. The dog washing station and the dog run are often messy. The garage door continues to break down. This winter, a rash of burglaries spooked residents.

Jeremiah said PHA is addressing these concerns, and in some cases — such as the dirty dog run — residents are expected to clean up after themselves. He also noted that the agency installed 24-hour security.

“The idea that this is a new phenomenon to that building, given where it’s located, is just nonsense,” Jeremiah said of the security concerns. “We have a very robust set of layered access control systems in place [and] CCTVs.”

As PHA was negotiating to buy The Dane, it also sought to save the Brith Sholom House, a dilapidated nearby senior complex linked to a national fraud scheme. After assessing the depths of the building’s issues, PHA determined that to repair it, tenants would have to move out.

When they first arrived at The Dane, some elderly residents were not getting the care they need, Washington said.

One man she ran into frequently often smelled of urine and would walk around with visibly wet pants. She said building management addressed the issues by spraying Febreze on benches the tenant used after he left an area. He has since died.

Another man screamed for help from his balcony and has since been moved out of the building.

“We are very used to all kinds of things happening here, from the students being wild to elderly being wild, but not to the level of being unable to take care of themselves,” Washington said.

Jeremiah says that PHA keeps tabs on the rehoused Brith Shalom residents — who previously were living with no oversight, although there are limits to what it can do. He encouraged tenants to report anyone who needs aid.

“We provide a robust set of social services to residents we inherited at Brith Shalom,” Jeremiah said. “PHA is not a healthcare provider. We are a housing provider, though we provide access to opportunities for residents who are interested in aging in place.”

A former Brith Shalom resident had no complaints with The Dane and praised PHA for the improvements in his life.

“I have no problem with them. I’m happy,” said Barry Brahn, who is blind and has AIDS. “They’re slow at getting things fixed, but they can only do so much and they’ll eventually get on it.”

What comes next?

Some aspects of the rocky transition from Cross Properties to PHA have eased. Since October, tenants were able to pay their rent online and submit maintenance requests. Washington says she does not see obviously distressed elderly residents any longer.

But tensions remain.

“The transition to PHA has been challenging, and their communication has been sorely lacking,” said Lanese Rogers, who has lived in The Dane for two years. “As someone who pays unsubsidized rent, they deal with us in a condescending manner.”

Jeremiah says he believes some of the pushback against PHA is due to class prejudice and bias against subsidized tenants.

“I don’t believe that there is anywhere any Philadelphian, whether or not they’re high income, middle income, low income, shouldn’t be permitted to live,” Jeremiah said.

He is committed to providing accessibility and affordability throughout the city, he said, and he hopes to retain mixed-income residency in newly acquired buildings with existing tenants.

So far at The Dane, many of the market-rate tenants are leaving.

“If I could pick up my apartment and move it to another location, I would,” Rogers said. “The building is changing, and I don’t like the direction it’s moving in.”