Talk to most nonprofit chief executives, and they’ll be able, on cue, to recite a heartwarming story about someone their organizations helped.

And the Rev. Luis Cortés Jr., Esperanza’s founder and chief executive, can do it, too.

But he’d rather talk about a sin he committed as a little boy — a sin that impacted his thinking for a lifetime and allowed him to understand how to build a $111.6 million organization with 800 employees that educates, develops, uplifts, and houses 35,000 people a year in the heart of North Philadelphia’s predominantly Hispanic Hunting Park neighborhood.

When Cortés was 12, he stole a Snickers candy bar from the bodega his father owned in New York City’s Spanish Harlem.

Oh, his father figured it out, and quickly, too, because he began to ask little Luis some important questions:

Did the 12-year-old know how many Snickers bars the bodega would have to sell to break even — not only on the box of Snickers, but on the taxes and utilities for the entire store? More importantly, how many Snickers bars would be required to turn a profit — a profit that could be reinvested?

“You need to understand finance, whether it’s a box of Snickers or a multimillion-dollar bond to build a school. Where is the money coming from, and what’s the repayment structure?” Cortés said.

Outside, as he spoke, a crane moved materials in what will soon become a new culinary school.

“Understanding finance is important, and understanding culture is important, and you have to understand the relationship between the two.”

So, yes, Cortés can and did tell the story about the mother who came to Esperanza to learn English skills, who got help to get a job and a house, who sent her daughter to Esperanza’s charter school and to Esperanza’s college, and now that same daughter is getting a house thanks to Esperanza’s mortgage counseling help.

All good. But this is what Cortés really wants people to know:

“If people trust us with their funds,” he said, “we’re putting the money into institutions, and institutions build culture.”

That’s why Esperanza has a K-12 charter school, a cyber school, a two-year college that’s a branch campus of Eastern University, a 320-seat theater, an art gallery, computer labs, an immigration law practice, a neighborhood revitalization office, a CareerLink office for workforce development and job placement, a music program, a youth leadership institute, housing and benefit assistance, and a state-of-the-art broadcasting facility.

Cortés even likes to brag about the basketball court. “Three inches of concrete, maple wood flooring, fiberglass backboards — NBA standards.”

“Think about Paoli. It has a hospital, a public school, a theater. Paoli has all of that, and it’s understood that that’s the quality of life. We have to have access to those same things at a different price point,” he said. “Notice I didn’t say different quality. I said different price point.

“We want to create an opportunity community, where people can have a good life — with arts, housing, healthcare, financial literacy, education, all those pieces — regardless of your family income,” he said.

“What’s important here and what’s different is that in all our places, all our facilities are first class,” Cortés said.

“I grew up in a low-income community where people were always telling you to step up, but step up to what?” he asked. “Where is the vision? What is possible to even have? How can anyone know unless they can see it?”

So, when people from the community visit Esperanza, “you can see that you can have the best facilities with state-of-the-art equipment. As a provider of services, we have to step up,” he said, in turn always giving people the tools and resources they need to step up.

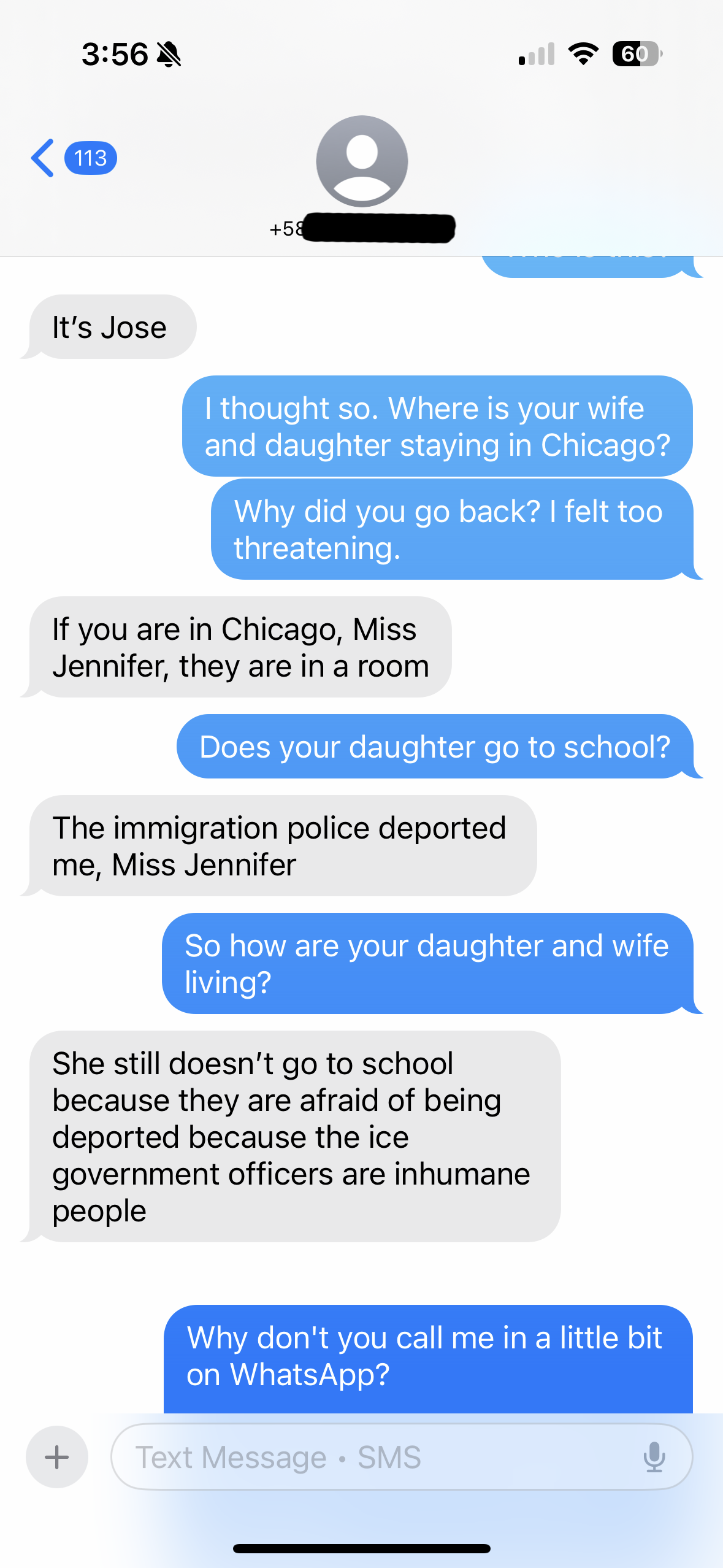

For example, on Citizenship Day, Sept. 20, Anu Thomas, an attorney and executive director of Esperanza’s Immigration Legal Services, trained a dozen volunteer lawyers and law students on the fine points and recent pitfalls in the process of applying for citizenship.

Soon, the room was crowded with people coming for help.

Watching from the sidelines was Charlie Ellison, executive director of the city’s Office of Immigrant Affairs, who noted that an estimated 60,000 legal residents of Philadelphia are eligible to apply for citizenship.

“Clinics like these are critically important to helping people who might be facing barriers,” including the cost of getting legal help. “This bridges a lot of gaps. It’s a vital mission, now more than ever,” he said.

For Neury “Tito” Caba, a men’s fashion designer, tailor, and director of green space at Historic Fair Hill, citizenship help from Esperanza was a family affair. Through Esperanza, he, his grandmother, and his mother all became citizens.

“Now I can vote, and that’s the most positive thing I can do,” he said. “And also, things being the way they are, it gives me some sort of protection.”

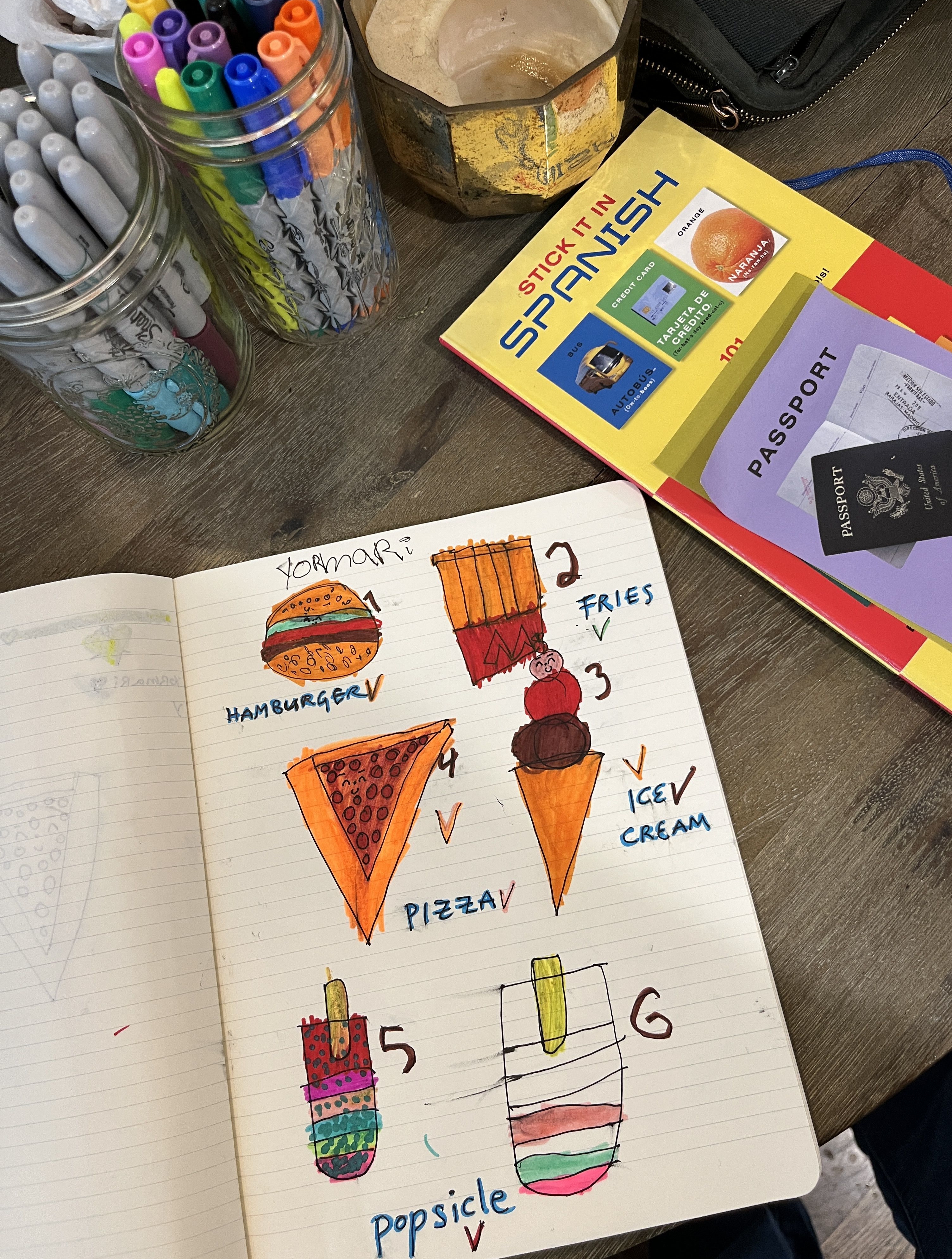

Earlier this fall at Esperanza’s CareerLink branch, counselor Sylvia Carabillo helped Luis Rubio on the computer. He was trying to extend his unemployment benefits and looking for a job as a security guard. Agueda Mojica was being tutored in Esperanza’s most popular workforce class: Introduction to Computers.

“I want to become more independent to be able to do anything on a computer,” she said in Spanish, speaking through a translator. “I was always working and never had time to learn.”

Much of Esperanza’s staff is bilingual in Spanish, but to help people from the neighborhood, Esperanza also hired counselors who speak Ukrainian and Kreyòl for Haitians who live nearby.

In Esperanza College classrooms a few weeks ago, Esperanza Academy high schoolers enrolled as college students had just finished a chemistry exam. When they graduate from high school, they’ll already have associate degrees on their résumés.

For them, Esperanza represents a future.

There’s Oryulie Andujar, 18, who wants to study sonography because an ultrasound technician found a cyst in her mother’s uterus. “We could have lost her. That was very impactful for me.”

Jayliani Casiano, 17, wants to go into anesthesiology. The oldest of seven, she witnessed her mother giving birth to several younger siblings. “She was in a lot of pain. It was interesting. I want to do everything after seeing her through that process.”

Derek Medina, 18, said the opportunity to go to college “made me rethink my whole life.” He had been getting into trouble in school, but now wants to combine a love of mathematics and a desire to help people by going into the field of biomedical engineering.

Recently, on Nov. 14, Esperanza College hosted its Ninth Annual Minorities in Health Sciences Symposium, designed to acquaint high schoolers with medical careers.

Construction will soon begin to convert a former warehouse space into a center to teach welding and HVAC in an apprenticeship program.

Next month, it’ll be time for “Christmas En El Barrio” with music, food, and community in Teatro Esperanza — admission is free. In January, the Philadelphia Ballet will perform there. Tickets are $15 and free for senior citizens and students.

“My worst seat — in Row 13 — would be $250 at the Academy of Music,” Cortés said. He wants to offer the arts at a price and a time available to a mother of three, who may not be able to afford even the cheapest seats in downtown venues, plus bus fare, “and heaven forbid the child wants a soda,” Cortés said.

All this adds up to culture, which brings him back to the Snickers bar, and not just breaking even, but investing.

Other groups, Cortés said, had to build their own institutions when mainstream organizations put up barriers. Howard University helped Black people, Brandeis served Jewish people, and Notre Dame provided education to the Irish.

Building an institution is his investment goal with Esperanza, and he takes as his mentors famous Philadelphia pastors such as the Rev. Leon Sullivan, who founded Progress Plaza in North Philadelphia, and the Rev. Russell Conwell, the Baptist minister who founded Temple University.

“Philadelphia has a tradition that its clergy don’t just do clergy things,” he said, admitting that he doesn’t have the patience for a more traditional pastor’s role. “As clergy here, it’s understood that we snoop around everything.”

Cities sometimes brag that their poverty rates have declined, he said, when in reality, rates have declined because people with low incomes were forced to move away.

Philadelphia, he said, has a chance to be different — to lower the poverty level both by raising people’s incomes and improving their standards of living. “There should be Esperanzas in every neighborhood,” he said.

“How can we focus on helping the people who just need a break?” Cortés said, referencing Jesus’ admonishment to “help the least of these.”

“This city has the opportunity to make this a win-win,” he said, “to show the rest of the country and Washington, D.C. — especially Washington, D.C. — that people who are different, and people who are `the other’ can be supported, so that they are not only part of the fabric of the city, but economic drivers of the city.”

This article is part of a series about Philly Gives — a community fund to support nonprofits through end-of-year giving. To learn more about Philly Gives, including how to donate, visit phillygives.org.

About Esperanza

People Served: 35,000

Annual Spending: $111.6 million across all divisions

Point of Pride: Esperanza empowers clients to transform their lives and their community through a diverse array of programs, including K-14 education, job training and placement, neighborhood revitalization and greening, housing and financial counseling, immigration legal services, arts programming, and more.

You Can Help: Esperanza welcomes volunteers for community cleanups, plantings, and other neighborhood events. Some programs also need volunteers with specific skills (lawyers, translators, etc.).

Support: phillygives.org

What Your Esperanza Donation Can Do

- $25 covers the cost of one private music lesson for a young student through our Artístas y Músicos Latinoamericanos program.

- $50 provides printing and distribution of 30 “Know Your Rights” brochures to immigrant families.

- $100 pays for five hours of training for a new mentor fellow at the Esperanza Arts Center, preparing a young person for a career in arts production through hands-on learning.

- $275 funds the planting of one street tree in a neighborhood that desperately needs additional tree cover to address extreme heat.

- $350 covers tuition and books for one English as a second language student at the Esperanza English Institute.

- $550 supports the cost of the initial work authorization for an asylum-seeker.