In Kensington, a program to mitigate street violence was hitting its stride.

After joining the New Kensington Community Development Corporation in 2023, outreach coordinators with Cure Violence began responding to shootings in the neighborhood, connecting folks with mental health services and other wellness resources.

They hosted men’s therapy groups, safe spaces to open up about the experience of poverty and trauma, and organized a recreational basketball league at residents’ request. Their team of violence interrupters even intervened in an argument that they said could have led to a shooting.

Cure Violence Kensington was funded by a $1.5 million federal grant from the Department of Justice, part of a Biden-era initiative to combat the nation’s gun violence epidemic by awarding funds to community-based anti-violence programs rather than law enforcement agencies.

One year after a political shift in Washington, however, federal grants that Philadelphia’s anti-violence nonprofits say allowed them to flourish are disappearing.

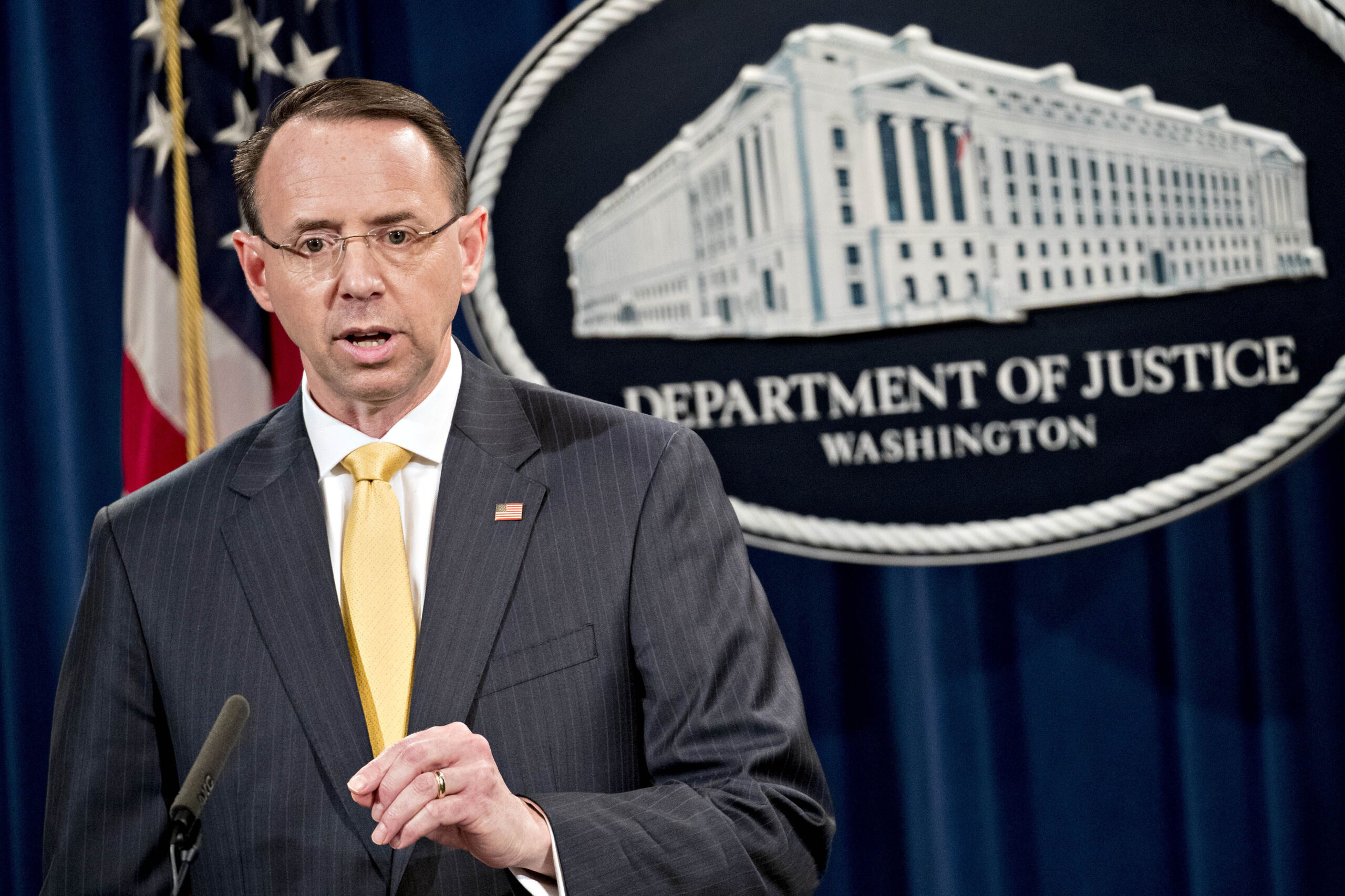

In the spring, New Kensington CDC received a letter from the Justice Department, saying that under the leadership of Attorney General Pam Bondi it had terminated the grant that would have funded Cure Violence for the next three years.

The work, the letter said, “no longer effectuates the program goals or agency priorities.” In the future, it said, the department would offer such grants exclusively to local law enforcement efforts.

“It was a heavy hit,” said Bill McKinney, the nonprofit’s executive director.

The cuts come amid a Trump administration crackdown on nonprofits and other organizations it views as either wasteful or focused on diversity and DEI.

It spent 2025 slashing funds for programs that supplied aid abroad, conducted scientific research, and monitored climate change. At the Justice Department, cuts came for groups like McKinney’s, which aim to target the root causes of violence by offering mental health services, job programs, conflict mediation, and other alternatives to traditional policing.

In Philadelphia, organizations like the Antiviolence Partnership of Philadelphia and the E.M.I.R. Healing Center say they, too, lost federal funding last year and expect to see further reductions in 2026 as they scramble to cover shortfalls.

A Justice Department spokesperson said changes to the grant program reflect the office’s commitment to law enforcement and victims of crime, and that they would ensure an “efficient use of taxpayer dollars.”

“The Department has full faith that local law enforcement can effectively utilize these resources to restore public safety in cities across America,” the spokesperson said in an email.

Nonprofits may appeal the decisions, the spokesperson said, and New Kensington CDC has done so.

Philadelphia city officials, for their part, say they remain committed to anti-violence programs, in which they have invested tens of millions of dollars in recent years.

“There are always going to be things that happen externally that we have no control over as a city,” said Adam Geer, director of the Office of Public Safety.

The reversal in federal support comes at a time when officials like Geer say the efforts of anti-violence programs are beginning to show results.

Violent crime in Philadelphia fell to historic lows in 2025, a welcome relief after the sharp upturn in shootings and homicides that befell the city at the height of the pandemic.

A variety of factors have contributed, from shifting policing tactics in Kensington to investigators solving homicides at record rates, putting more violent offenders behind bars. But advocates say local, state, and federal investments in anti-violence programs have played a significant role.

In 2021, the city announced a large-scale campaign to combat gun violence that, in the past year, included nearly $24 million for anti-violence programs.

That was on top of the Biden administration’s Community Based Violence Intervention and Prevention Initiative. Since launching in 2022, the DOJ program awarded more than $300 million to more than 120 anti-violence organizations nationwide.

In April, many of those groups, including New Kensington CDC, lost funds. And in September, a larger swath learned they were now barred from applying for other Justice Department grants that would have arrived this spring.

“We’ve seen enormous dividends” from the work of such groups, said Adam Garber, executive director of CeaseFirePA, a leading gun violence prevention group in the state. “Pulling back now puts that progress at risk — and puts lives on the line.”

Philadelphia feels the squeeze

Federal grants helped Natasha McGlynn’s nonprofit thrive.

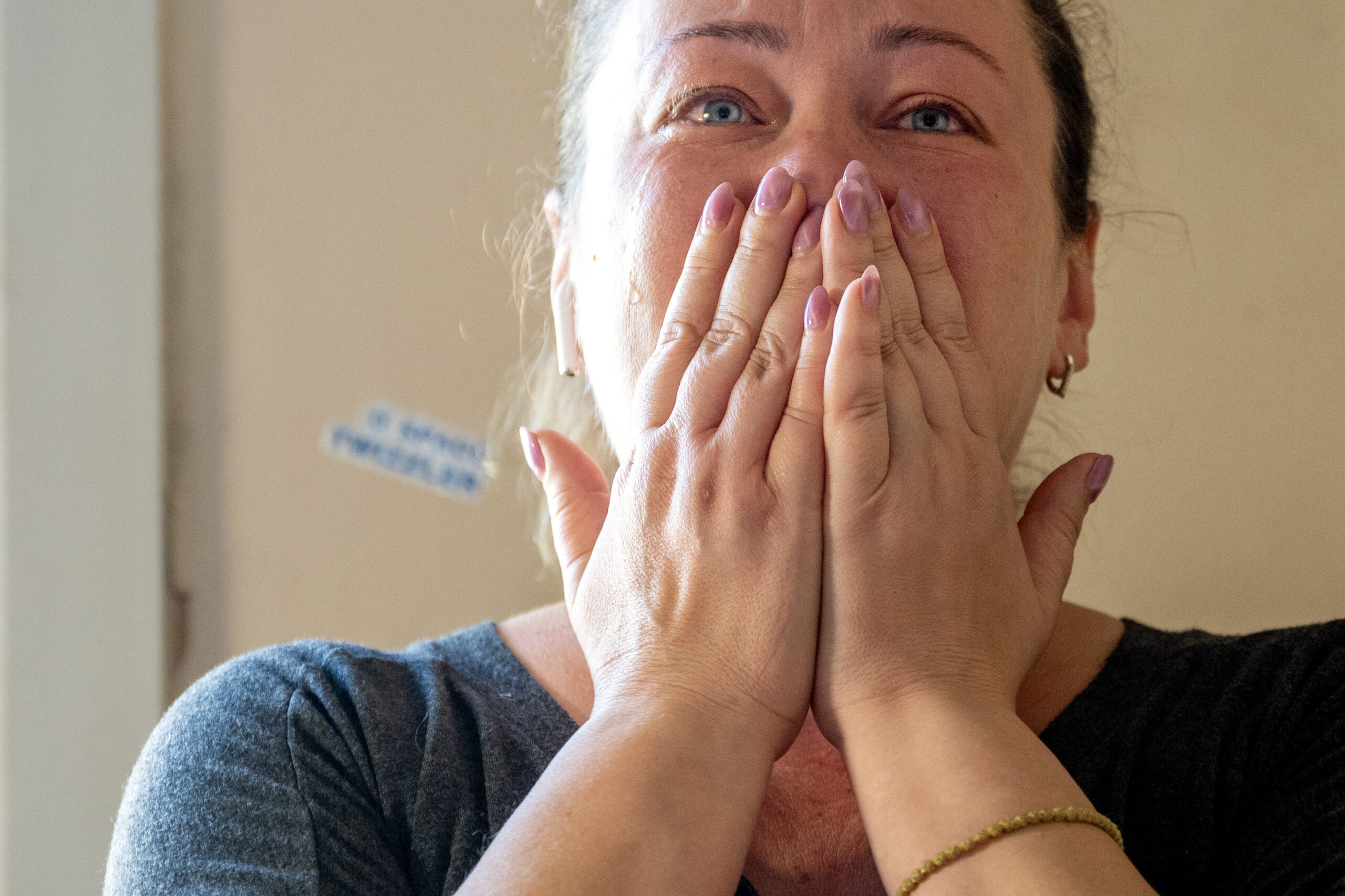

McGlynn, executive director of the Antiviolence Partnership of Philadelphia, said a DOJ grant called STOP School Violence allowed her organization to launch a counseling program for young people who had been victims of violence or otherwise exposed to it in some of the city’s most violent neighborhoods.

The nonprofit used the grant to hire therapists to help students develop healthier attitudes around conflict and trauma, she said.

The $997,000 grant was cut in April, and when McGlynn went to apply for another round of funding in the fall, she learned that nonprofits were no longer eligible. The lost funding means some services, like counseling, could now be eliminated, she said.

“I would say several positions are in question,” McGlynn said. “I would say the program is in question.”

Chantay Love, the director of Every Murder is Real, said her Germantown-based victim services nonprofit also lost Justice Department funding in 2025.

Federal grants are not the nonprofit’s only source of income, Love said, but she along with other nonprofit leaders in the city are considering whether they’ll need to cut back on programs this year.

Record-setting investment

The decade before the pandemic saw gun-related deaths in the state climb steadily, spiking during the lockdown as social isolation, school closures, shuttered community services, and higher levels of stress contributed to a spate of gun homicides and shootings that began to ease only in 2024.

Two years earlier, the state began dispersing more than $100 million to community-based anti-violence programs, much of the money coming from the American Rescue Plan, a sweeping Biden administration pandemic recovery package that also sought to reduce rising gun violence. And when those funds expired, state lawmakers continued to invest millions each year, as did Philadelphia city officials.

Garber, of CeaseFirePA, said those efforts “get a lot of heavy-lifting credit” for Philadelphia’s historic decrease in violence.

A report compiled by CeaseFirePA cites studies that found outreach programs like Cure Violence helped reduce shootings around Temple University, as well as in cities like New York and Baltimore, where homicides and shootings in some parts of the city fell by more than 20%.

While it’s too early for data to provide a full picture on how such funding has contributed to overall violence reduction, officials like Geer, the Philadelphia public safety director, agreed that programs like Cure Violence have helped crime reach record lows.

Outreach workers with the city-supported Group Violence Intervention program made more than 300 contacts with at-risk residents in 2025, according to data provided by Geer’s office, either offering support or intervening in conflicts.

And they offered support to members of more than 140 street groups — small, neighborhood-oriented collectives of young people that lack the larger organization of criminal gangs — while more than doubling the amount of service referrals made the previous year.

In practice, a program’s success looks like an incident in Kensington in which Cure Violence workers intervened in a likely shooting, according to members of New Kensington CDC.

In April, a business owner called on the nonprofit after seeing a group of men fighting outside his Frankford Avenue store and leaving to return with guns. Members of the outreach team spoke with both parties, de-escalating the conflict before it potentially turned deadly.

“Each dollar cut is ultimately a potential missed opportunity to stop a shooting,” Garber said.

Cutting off the ‘spigot’

Even as community-based anti-violence programs have risen in popularity, they are not without their critics.

While some officials champion them as innovative solutions to lowering crime, others say the programs can lack oversight and that success is difficult to measure.

In 2023, an Inquirer investigation found that nonprofits with ambitious plans to mitigate gun violence received millions in city funds, but in some cases had no paid staff, no boards of directors, and no offices.

A subsequent review by the Office of the Controller found some programs had not targeted violent areas or had little financial oversight. But by the next round of funding, the city had made improvements to the grant program, the controller’s office found, adding funding benchmarks and enhanced reporting requirements.

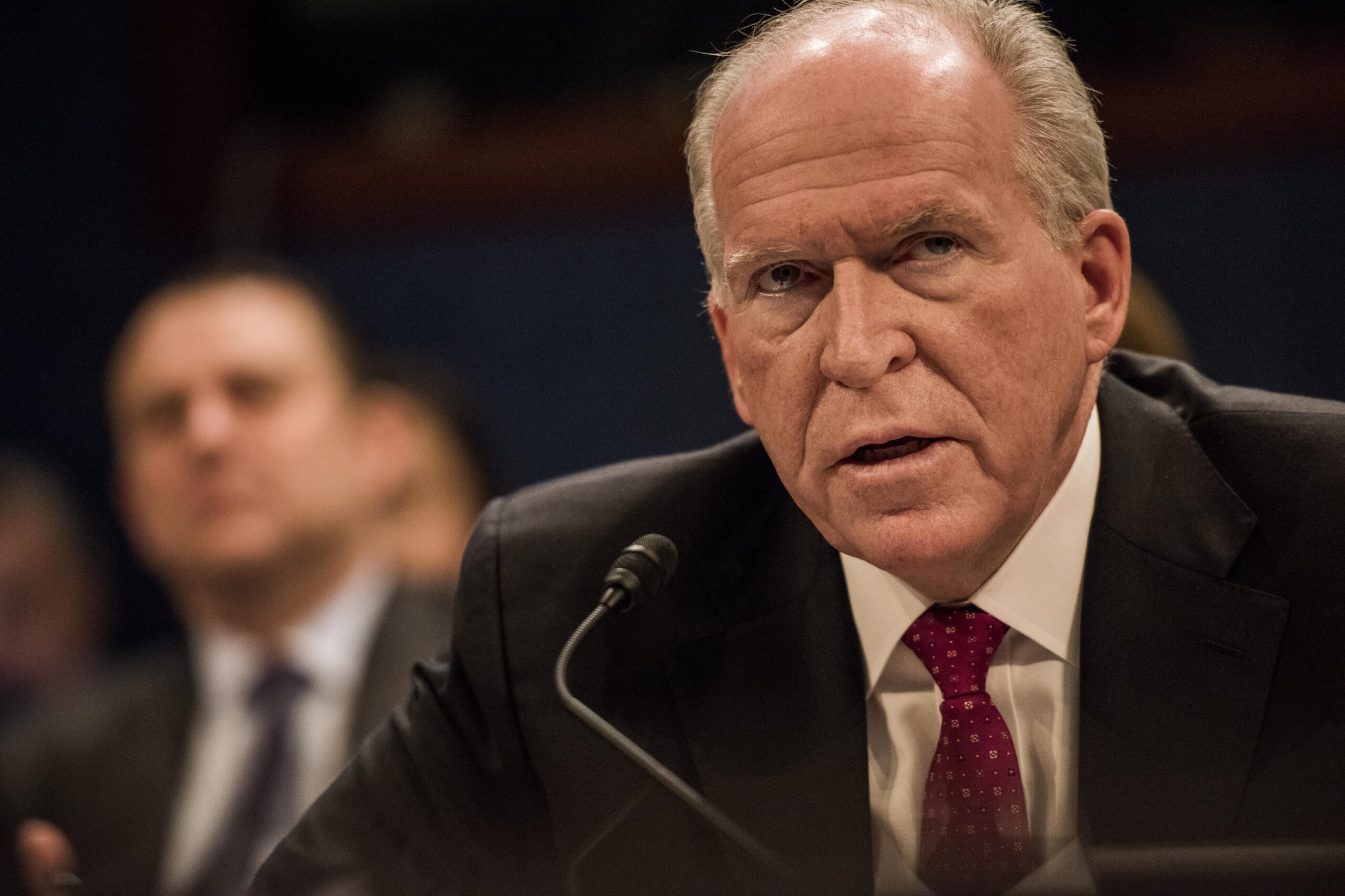

Meanwhile, as Philadelphia continued its support these programs, President Donald Trump’s Justice Department began a review of more than 5,800 grants awarded through its Office of Justice Programs. It ultimately made cuts of more than $800 million that spring.

Among programs that lost funding, 93% were “non-governmental agencies,” including nonprofits, according to a letter DOJ officials sent to the Senate explaining the decision.

The balance of remaining funds in the violence prevention grant program — an estimated $34 million — will be available for law enforcement efforts, according to a DOJ grant report. In addition to fighting crime, the money will help agencies improve “police-community relations,” hire officers, and purchase equipment, the document says.

Agencies conducting immigration enforcement are also eligible for grants, the report says, while groups that violate immigration law, provide legal services to people who entered the country illegally, or “unlawfully favor” people based on race are barred.

One group lauding the cuts is the National Rifle Association, which commended the Trump administration in November for cutting off the “spigot” to anti-violence nonprofits.

‘[T]he changes hopefully mean that nonprofits and community groups associated with advocating gun control will be less likely to do it at the expense of the American taxpayer and that real progress can occur on policing violent criminals,” the NRA’s legislative arm wrote in a blog post that month.

Nate Riley disagrees.

Riley, an outreach worker with Cure Violence Kensington, said the cuts threaten to reverse the progress New Kensington CDC has made since he joined the program early last year.

Cure Violence’s six-person outreach team is made up of people like Riley, who grew up in North Philadelphia and says he is well-versed in the relationship between poverty, trauma, and violence and brings that experience to Kensington.

“This is a community that’s been neglected for decades,” Riley said. “For lack of a better term, you’ve got to help them come in outside of the rain.”

In a recent month, Cure Violence outreach workers responded to 75% of shootings in the Kensington area within three days, a feat Riley is particularly proud of.

He said the program is not meant to supplant the role of police.

Instead, Riley sees street outreach as another outlet for those whose negative experiences with authorities have led them to distrust law enforcement.

Those people may alter their behavior if they know police are present, he added, giving outreach workers embedded in the community a better chance at picking up on cues that someone is struggling.

From Kensington to Washington

McKinney, with New Kensington CDC, said the group was still expecting about $600,000 from the Justice Department when the grant was cut short.

The nonprofit has since secured a patchwork of private donations and state grants that will keep Cure Violence running through much of 2026, he said.

After that, the program’s future is uncertain.

In the wake of the cuts, national organizations like the Community Justice Action Fund are advocating for federal officials to preserve funding for community-based anti-violence programs in future budgets. Adzi Vokhiwa, a federal policy advocate with the fund, said the group has formed a network of anti-violence nonprofits dubbed the “Invest in Us Coalition” to do so.

The group petitioned congressional leadership in December to appropriate $55 million for anti-violence organizations in the next budget — a figure that both Democrats and Republicans in the Senate have previously agreed on and that Vokhiwa views as a sign of bipartisan support for such programs.

McKinney, with New Kensington CDC, said it was impossible to ignore that the nonprofit and others like it provide services to neighborhoods where residents are overwhelmingly Black and brown. In his view, the cuts also reflect the administration’s “war on cities.”

He was bothered that the Justice Department did not seem to evaluate whether New Kensington CDC’s program had made an impact on the neighborhood before making cuts.

“We’re in a situation where the violence isn’t going away,” he said. “Even if there’s been decreases, the reality is that Kensington still leads the way. As those cuts get deeper, we are going to see increases in violence.”