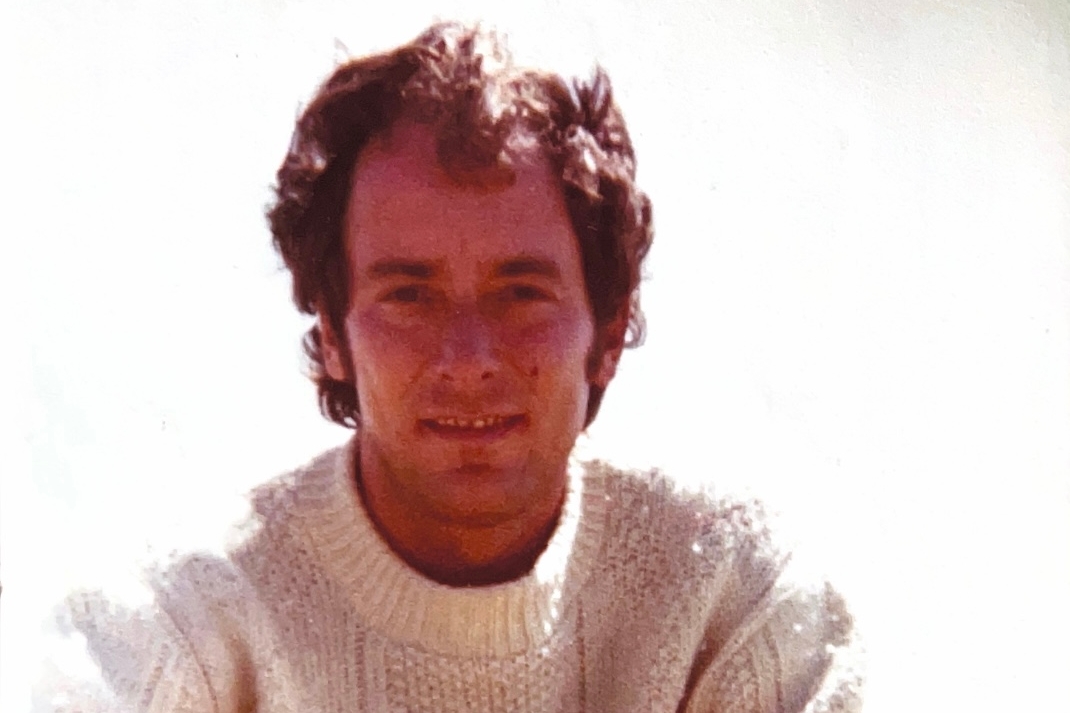

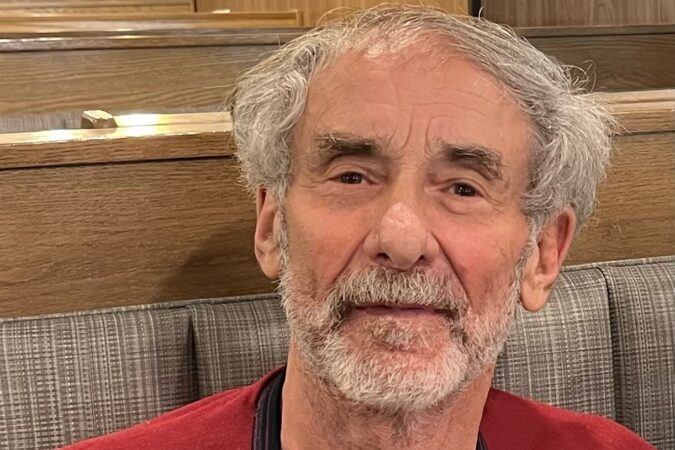

Craig Kellem, 82, of Philadelphia, former talent agent, celebrated TV producer, show developer, writer, longtime script consultant, author, and “comedic genius,” died Monday, Nov. 24, of complications from dementia at Saunders House assisted living in Wynnewood.

Born in Philadelphia, Mr. Kellem moved to New York as a teenager and, at 22, burst onto the entertainment scene in 1965 as a talent scout and agent for what was then called Creative Management Associates. He rose to vice president of the company’s TV Department and, over the next 30 years, served as director of development for late night, syndication, and daytime TV at 20th Century Fox Television, vice president of comedy development at Universal Television, and executive vice president of the Arthur Co. at Universal Studios.

He worked with fellow TV producer Lorne Michaels at Above Average Productions in the 1970s and was a popular associate producer for the first season of Saturday Night Live in 1975 and ’76. He was quoted in several books about that chaotic first season, and his death was noted in the show’s closing credits on Dec. 6.

At Universal Studios, he created and produced FBI: The Untold Stories in 1991. At Universal Television in the 1980s, he developed nearly a dozen shows that aired, including Charles in Charge and Domestic Life in 1984. In 1980, he developed Roadshow for 20th Century Fox Television.

“He had a lot of energy and ideas,” said his wife, Vivienne. “He had a creative spirit.”

His producing, creating, developing, and writing credits on IMDb.com also include The Munsters Today, The New Adam-12, Dragnet, and What a Dummy. He produced TV films and specials, and worked on productions with Eric Idle, Gladys Knight, Sammy Davis Jr., and the Beach Boys.

In 1998, he and his daughter, Judy Hammett, cofounded Hollywoodscript.com and, until his retirement in 2021, he consulted for writers and edited and critiqued screenplays. In 2018, they coauthored Get It On the Page: Top Script Consultants Show You How.

“He loved working with writers,” his daughter said. “He was super creative. It was part of his essence.”

As an agent in the 1960s and ’70s, Mr. Kellem represented George Carlin, Lily Tomlin, and other entertainers. His eye for talent, dramatic timing, and sense of humor were legendary.

“My dad’s humor opened hearts, tore down walls, and allowed people to connect with each other’s humanity, vulnerability, and spirit,” said his daughter Joelle. His daughter Judy said: “He was a comedic genius.”

His wife said: “He was a fascinating, funny, loving, and sensitive man.”

Craig Charles Kellem was born Jan. 24, 1943. He grew up with a brother and two sisters in West Mount Airy, played with pals in nearby Carpenter’s Woods, and bought candy in the corner store at Carpenter Lane and Greene Street.

“Craig was like a father to me,” said his brother, Jim. “He helped guide my children and was always there for the whole family.”

He graduated from high school in New York and moved up to senior positions at Creative Management Associates after starting in the mailroom. He married in his 20s and had a daughter, Judy.

After a divorce, he met Vivienne Cohen in London in 1977, and they married in 1980, and had a son, Sean, and a daughter, Joelle. He and his wife lived in California, Washington, New Hampshire, and New Jersey before moving to Fairmount in 2017.

Mr. Kellem enjoyed movies, walking, and daily workouts at the gym. He volunteered at shelters, helped underserved teens, and routinely carried dog treats in his car in case he encountered a stray in need. “That’s the kind of man Craig was,“ his wife said.

His son, Sean, said: “My dad’s personality was big, and he was deeply compassionate toward other human beings.” His daughter Joelle said: “He was an open, sensitive, warm, and passionate human being who believed deeply in the work of bettering oneself and taking care of others.”

His daughter Judy said: “They don’t make people like my dad.”

In addition to his wife, children, and brother, Mr. Kellem is survived by four grandchildren and other relatives. Two sisters died earlier.

Private services are to be held later.

Donations in his name may be made to the Alzheimer’s Association, 399 Market St., No. 250, Philadelphia, Pa. 19106; and Main Line Heath HomeCare and Hospice, 240 N. Radnor Chester Rd., Suite 100, Wayne, Pa. 19087.