Police found the body of the woman with the crystal pendant necklace stuffed beneath a wooden pallet in an overgrown lot in Frankford one night last June. She had been shot once between the eyes, and wore only a sports bra, with her pants and underwear tangled around her ankles.

Days in the stifling heat had left her face unrecognizable, nearly mummified.

Still, Homicide Detective Richard Bova could see traces of the beautiful young woman she had been. She was small, about 100 pounds, with long dark hair tinted red at the ends. Her nails were painted pale pink. She wore small gold hoops in her ears.

But he didn’t know her name. And for 90 days, the absence of that essential fact stalled everything.

A victim’s identity is the foundation on which a homicide case is built. Without it, detectives cannot retrace a person’s final moments or home in on who might have wanted them dead and why. For three months, Bova and his partner scoured surveillance footage, checked missing-persons reports, and ran down every faint lead, eager to put a name to the woman beneath the pallet.

At the same time, in a small house in Northeast Philadelphia, a family was searching, too.

Olga Sarancha hadn’t heard from her 22-year-old daughter, Anastasiya Stangret, in weeks and was growing worried. Stangret had struggled with an opioid addiction in recent months, but never went more than a few days without speaking to her mother or sister.

Through July and August that summer, Sarancha and her youngest daughter, Dasha, tried to report Stangret missing, but they said they were repeatedly rebuffed by police who turned them away and urged them to search Kensington instead.

So they kept checking hospitals, calling Stangret’s boyfriend, and driving through the dark streets of Kensington — looking for any sign that she was still alive.

It was not until mid-September that the family was able to file a missing-persons report. Only then did Bova learn the name of his victim.

But by then, he said, the crucial early window in the investigation had closed — critical surveillance footage, which resets every 30 days, was gone. Cell phone data and physical evidence were harder to trace.

Still, for 18 months, Bova has worked to solve the case, and for 18 months, Stangret’s mother and younger sister have grieved silently, haunted by the horrors of her final moments and the fear that her killer might never be caught.

Philadelphia’s homicide detectives this year are experiencing unprecedented twin phenomena: The city is on pace to record its fewest killings in 60 years, and detectives are solving new cases at a near-record high.

But those gains do not erase the reality that hundreds of killings in recent years remain unresolved — each one leaving families suspended in despair, and detectives asking themselves what more they could have done.

In this case, extensive interviews with Bova and Stangret’s family offer a window into how a case can stall even when a detective puts dozens of hours into an investigation — and what that stall costs.

Bova has a suspect: a 58-year-old man with a lengthy criminal record who he believes had grown infatuated with Stangret as he traded drugs for suboxone and sex with her. But the evidence is largely circumstantial. He needs a witness.

And Stangret’s family needs closure — and reassurance that the life of the young woman, despite her struggles, mattered.

“Everybody has something going on in their life,” said Dasha Stangret, 23. “It doesn’t make her a bad person, and it’s not what she deserved.”

Becoming Anna

Anastasiya Stangret was born in Lviv, Ukraine, on Nov. 15, 2001. Her family immigrated to Northeast Philadelphia when she was 8 and Dasha was 7.

The sisters were inseparable for most of their childhood. They cuddled under weighted blankets with cups of tea. They put on fluffy robes and did each other’s eyebrows and nails.

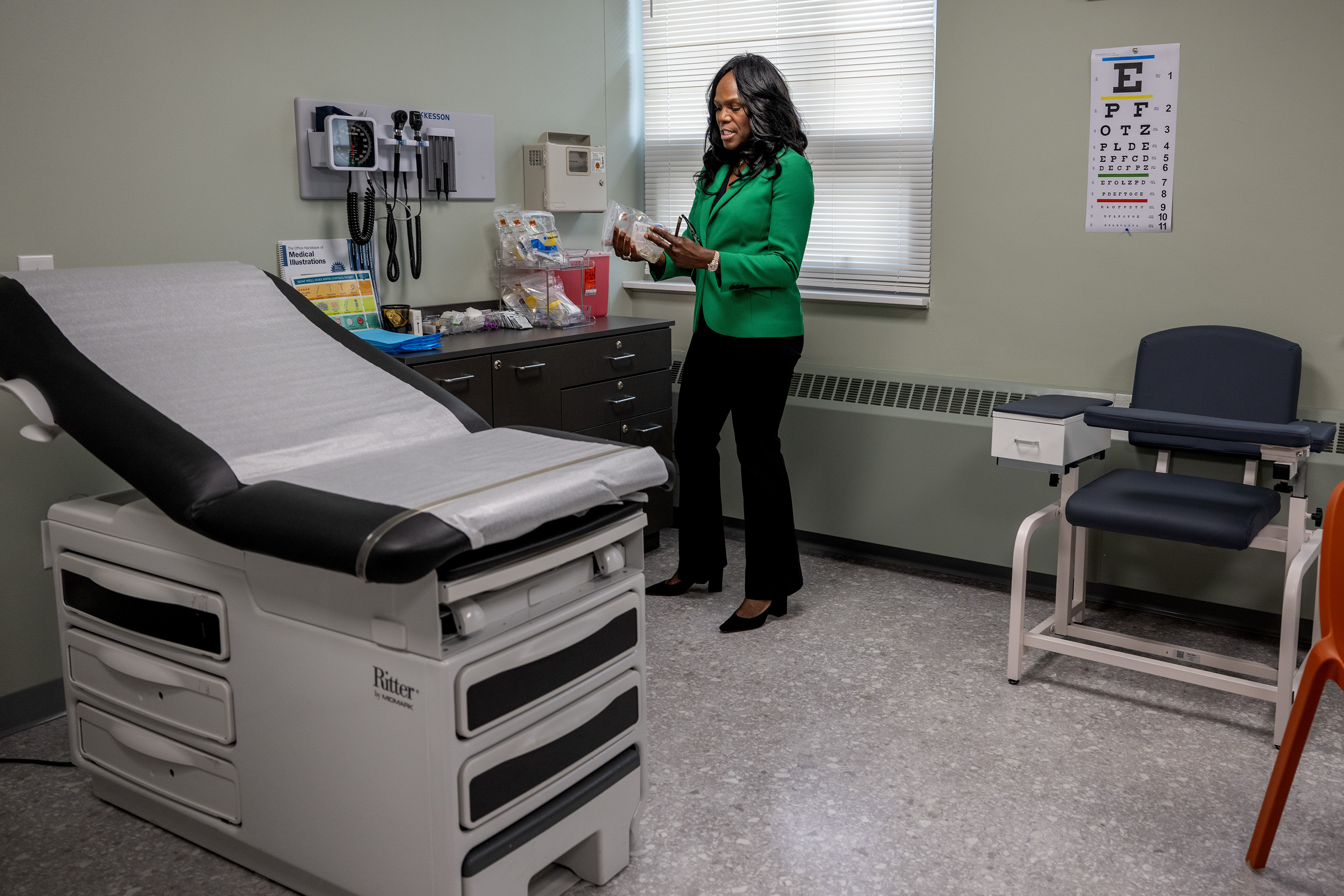

Anna was bubbly, polite, and gentle, her family said. She enjoyed working with the elderly, and after graduating from George Washington High School, she earned certifications in phlebotomy and cardiology care. She volunteered at a nearby food bank, translated for Ukrainian and Russian immigrants, and later worked at a rehabilitation facility, where she gave patients manicures in her free time.

“Anna always worked really hard,” Dasha Stangret said. “I looked up to her.”

But her sister was also quietly struggling with a drug addiction.

Her challenges began when she was 12, her mother said, after she was hit by a car while crossing the street to catch the school bus. She suffered a serious concussion, Sarancha said, and afterward struggled with PTSD, anxiety, and depression.

About a year later, as her anxiety worsened, a doctor prescribed her Xanax, her mother said. Not long after, she started experimenting with drugs with friends, her sister said — first weed, then Percocet.

She hid her drug use from her family until her early 20s, when she became addicted to opioids.

She sought help in January 2024 and began drug treatment. But her progress was fleeting. She returned to living with her boyfriend of a few years, who they later learned also used drugs, and she became harder to get in touch with, her mother said.

When Sarancha’s birthday, June 18, came and passed in 2024 without word from her daughter, the family grew increasingly concerned.

They checked in with Stangret’s boyfriend, they said, but for weeks, he made excuses for her absence. He told them that she was at a friend’s house and had lost her phone, that she was in rehab, that she was at the hospital.

On July 27, Sarancha and her daughter visited the 7th Police District in Northeast Philly to report Anna missing, but they said an officer told them to go home and call 911 to file a report.

Two officers responded to their home that day. The family explained their concerns — Stangret was not returning calls or texts, and her boyfriend was acting strange. But the officers, they said, told them they could not take the missing-persons report because Stangret no longer lived with them. They recommended that the family go to Kensington and look for her.

Through August, the family visited a nearby hospital looking for Stangret, only to be turned away. Sarancha, 46, and her husband drove through the streets of Kensington without success. They continued to contact the boyfriend, but received no information.

They wanted to believe that she was OK.

On Sept. 12, they visited Northeast Detectives to try to file a missing-persons report again, but they said an officer said that was not the right place to make the report. They left confused. Dasha Stangret called the district again that day, but she said the officer on the phone again told her that she should go to Kensington and look for her sister.

That the family was discouraged from filing a report — or that they were turned away — is a violation of Philadelphia police policy.

“When in doubt, the report will be taken,” the department’s directive reads.

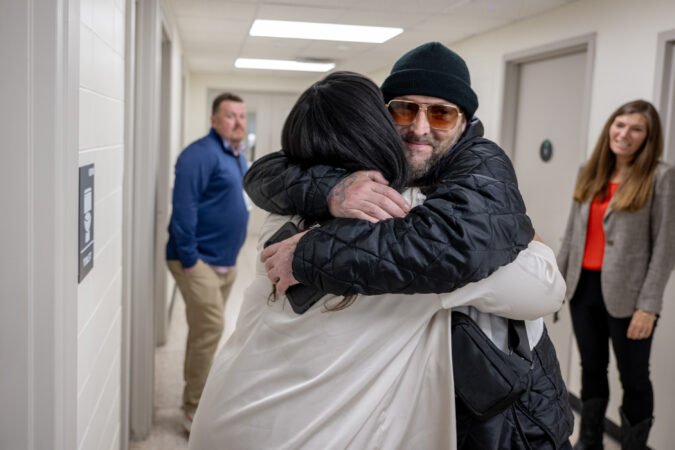

Finally, on the night of Sept. 12, Dasha Stangret again called 911, and an officer came to the house and took the missing-persons report. For the first time, they said, they felt like they were being taken seriously.

A few days later, Dasha Stangret called the detective assigned to the case and asked if there was any information. He asked her to open her laptop and visit a website for missing and unidentified persons.

Scroll down, he told her, and look at the photos under case No. 124809.

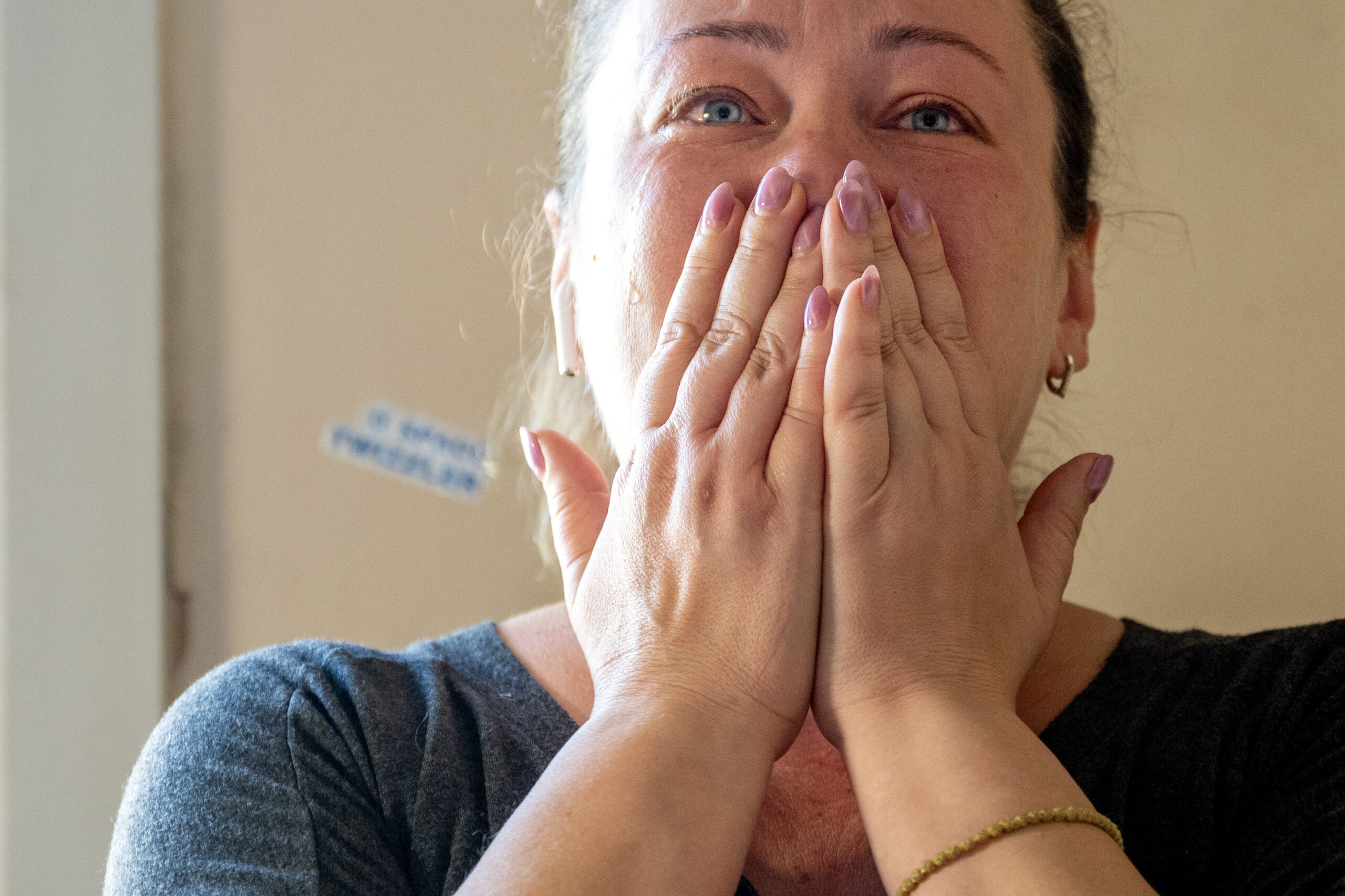

On the screen was her sister’s jewelry.

A detective’s hunch

Three months into Bova’s quest to identify the woman under the pallet — of watching hundreds of hours of surveillance footage and chasing fleeting missing-persons leads — dental records confirmed that the victim was Stangret.

After meeting with her family, Bova questioned the young woman’s boyfriend.

He told the detective he and Stangret had met a man under the El at the Arrott Transit Center in Frankford sometime in June, Bova said, and that the man gave them drugs in exchange for suboxone and, later, sex with Stangret.

But the man had grown infatuated with Stangret, he said, and after she left his house, he started threatening her in Facebook messages, ordering her to return and saying that if anybody got in his way, he would hurt them.

The man lived in a rooming house on Penn Street — almost directly in front of the overgrown lot where Stangret’s body was found. Surveillance video showed Stangret walking inside the rowhouse with him just before 7 p.m. on June 18, Bova said, but video never showed her coming back out.

Police searched the man’s apartment but found nothing to link him to the crime — no blood, no gun, no forensic evidence that Stangret had ever been inside. The suspect had deleted most of the texts and calls in his phone from June, July, and August, Bova said, and because nearly four months had passed, they could no longer get precise phone location data.

He said that, at this point, he does not believe the boyfriend was involved with her death, and that he came up with excuses because he was afraid to face her family.

Surveillance cameras facing the lot where Stangret was found didn’t show anyone entering the brush with a body. Neighbors and residents of the rooming house said they didn’t know or hear anything, he said. And a woman seen on camera pacing the block and talking with the suspect the night they believed Stangret was killed also said she had no information.

The detective is stuck, he said.

“Is it enough for an arrest? Sure,” Bova said of the circumstantial evidence against the suspect. “But our focus is securing a conviction.”

Bova’s theory is that the man, angry that Stangret wanted to leave, shot her in the head. Because the house has no back door, he believes the man then lowered her body out of the second-floor window, used cardboard to drag her through the brush, and then hid her under a pallet.

He is sure that someone has information that could help the case — that the suspect may have bragged about what happened, that a neighbor heard a gunshot or saw Stangret’s body being taken into the lot.

There is a $20,000 reward for anyone who has information that leads to an arrest and conviction.

“The hardest part is patience,” he said. “I’m looking for any tips, any information.”

Bova has worked in homicide for five years. As with all detectives, he said, some cases stick with him more than others. Stangret’s is one of them.

“Anna means a lot,” he said. “This is a young girl. We all have children. I have daughters. For her to be thrown in an empty lot and left, to see her life not matter like that, it’s horrifying to me and to us as a unit.”

“It eats me alive,” he said, “that I don’t have answers for them and I’m not finishing what was started.”

‘I love you. I miss you’

Stangret’s family suffers every day — the guilt of wondering whether they could have done more to get her help, the anger that her boyfriend didn’t raise his concerns sooner, the fear of knowing the man who killed her is still out there.

Dasha Stangret, a graphic design student at Community College of Philadelphia, finds it difficult to talk about her sister at length without trembling. It’s as if the grief has sunk into her bones.

In July, she asked a police officer to drive her to the lot where her sister’s body was found. She sat for almost an hour, crying, placing flowers, searching for a way to feel closer to her.

Sarancha struggles to sleep. She wakes up early in the mornings and rereads old text messages with her daughter. She pulls herself together to care for her 6-year-old son, Max, whose memories of his oldest sister fade daily.

On a recent day, Dasha Stangret and her mother visited her sister’s grave at William Penn Cemetery. They fluffed up the fresh roses, rearranged the tiny fairy garden around her headstone, and lit a candle.

Stangret began to cry — and shake. Her mother took her arm.

“I love you. I miss you,” Stangret told her sister. “I hope you’re happy, wherever you are.”

And nearly 20 miles south, inside the homicide unit, Bova continues to review the files of the case, waiting for the results of another DNA test, hoping for a witness who may never come.

If you have information about this crime, contact the Homicide Unit at 215-686-3334 or submit a confidential tip by texting 773847 or emailing tips@phillypolice.com.