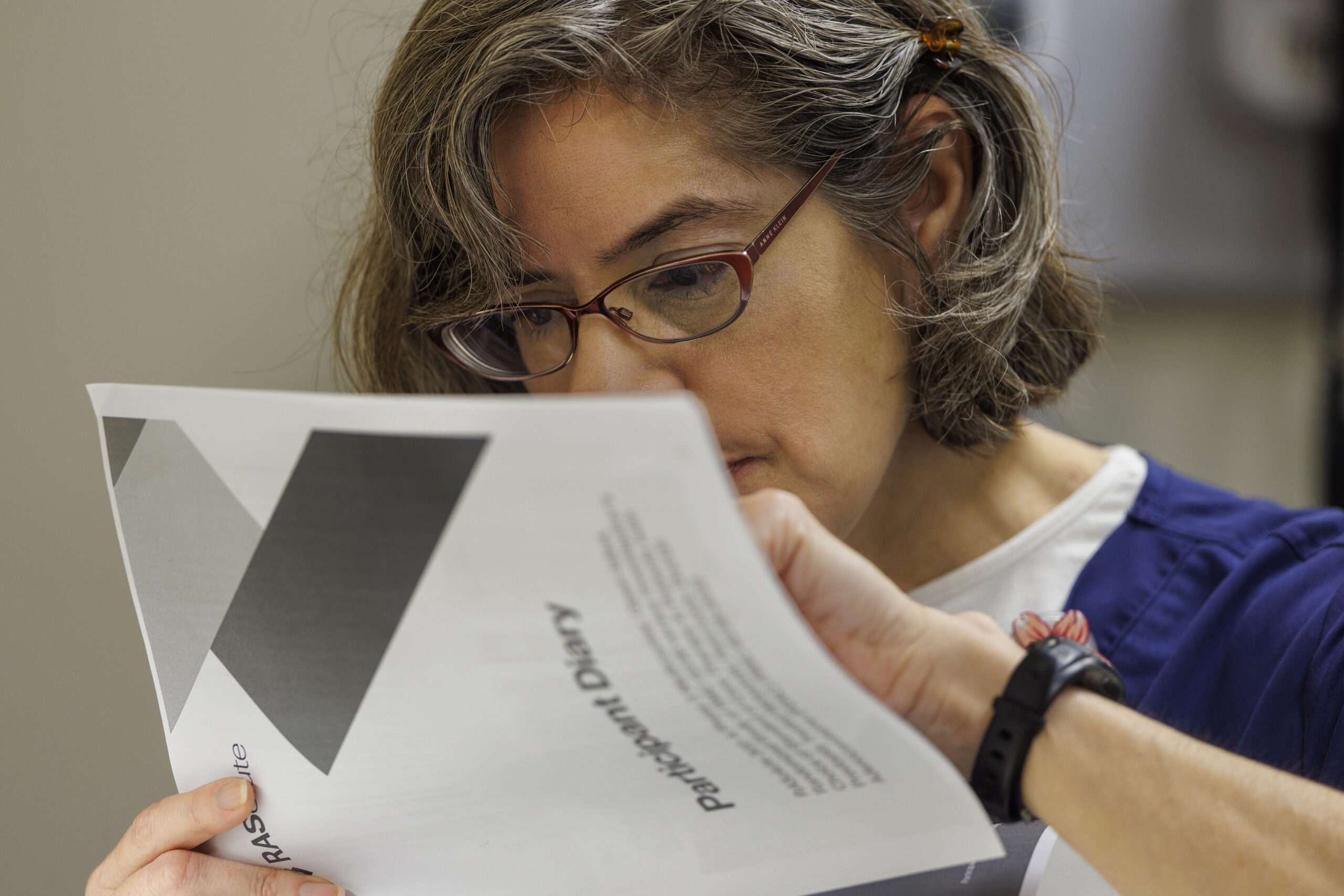

At Penn Medicine’s clinic where adults receive genetic counseling and testing, about 9% of patients are Black.

By contrast, one in four patients at the cardiology and endocrinology clinics located in the same facility in West Philadelphia are Black, while nearly 40% of city residents are. Those from low-income neighborhoods are also less likely to be seen at the genetics clinic, yet more likely to have positive results when tested, a recent Penn study found.

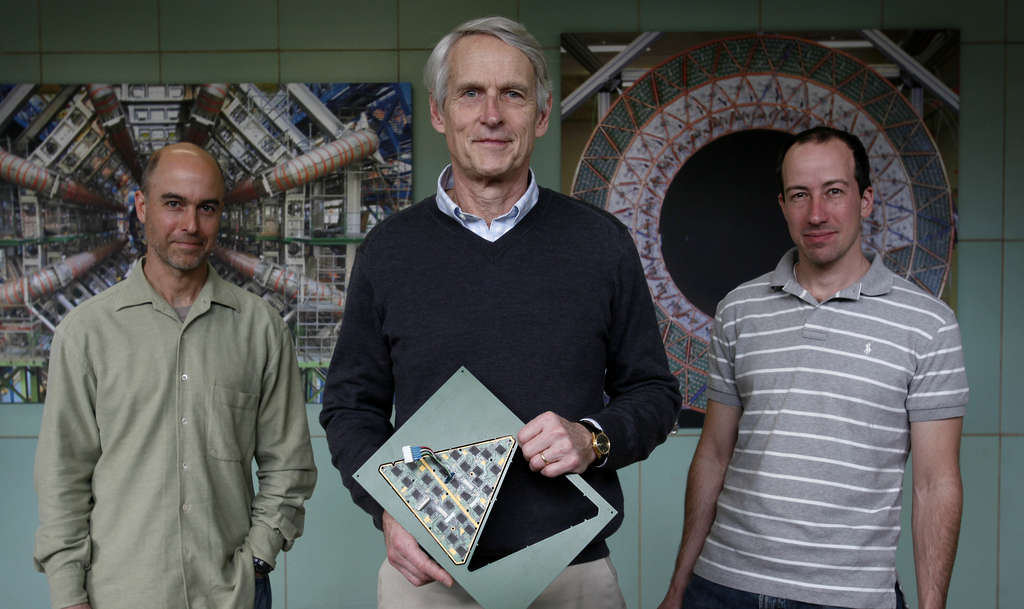

These findings line up with what Theodore Drivas, a clinical geneticist and the study’s senior author, had long suspected about the impact of racial disparities based on his own experience seeing patients at Penn’s clinic.

The study, published this month in the American Journal of Human Genetics, found that Black patients were also less likely to be represented at adult genetics clinics at Mass General Brigham, a Harvard-affiliated health system in Massachusetts.

There’s no biological reason why rates of testing should differ, Drivas said. The overall rate of genetic disease should be similar regardless of race, even though certain diseases are more prevalent in some populations.

“Genetic disease doesn’t favor one group or another,” he said.

That means if one group isn’t getting tested as much, they’re probably missing out on key diagnoses.

Racial disparities are an ongoing concern in medicine and have been attributed to a wide range of causes, including socioeconomic factors, unequal access to care, implicit bias, and medical mistrust due to historic injustices.

In a study published last August, Drivas’ team found that the chances of a genetic condition being caught varied widely by race. Among patients admitted to intensive care units across the Penn health system, 63% of white patients knew about their genetic condition, compared to only 22.7% of Black patients.

To address these disparities, Drivas is calling for changes to how the medical field approaches genetic testing, such as by integrating testing into standard protocols and improving national guidelines.

“It’s not just a Penn problem or a Harvard problem. It’s a genetics problem in general,” Drivas said.

Diving into the disparities

Drivas’ team analyzed data from 14,669 patients who showed up at adult genetics clinics at Penn and Mass General Brigham between 2016 and 2021. The findings are limited to the two major academic centers on the East Coast, which tend to see sicker patients compared to community medical centers.

Black patients were 58% less likely to be seen at Penn’s genetics clinic than would be expected based on the overall University of Pennsylvania Health System patient population.

At Mass General Brigham, Black patients were 55% less likely than would be expected based on that system’s population.

Some literature has suggested that Black patients and others from minority groups are less likely to agree to genetic testing because of an inherent distrust in the medical system due to historic injustices. “But we don’t see that in our data,” Drivas said.

Once evaluated at Penn’s clinic, Black patients were 35% more likely to have testing ordered than white individuals.

His team also found disparities affecting lower-income individuals. Each $10,000 increase in the median household income of a person’s neighborhood was associated with a 2% to 5% higher likelihood of evaluation at a genetics clinic.

Meanwhile, patients from neighborhoods with lower median socioeconomic status were more likely to get positive results from testing than those from wealthier neighborhoods.

“We’re relatively over-testing the people from higher socioeconomic brackets and under-testing the people from lower socioeconomic brackets,” Drivas said.

The solution is not to stop testing the wealthier people, he clarified, but to improve access to testing for others.

Undoing disparities

People who want to get a genetic diagnosis often have to go to major medical centers.

The University of Pennsylvania health system comprises seven hospitals across Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Its Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine, adjacent to the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in West Philadelphia, is the only one that has an adult genetics clinic.

Drivas has many patients who drive two or three hours to be seen for genetic testing.

The current wait time at his clinic is around three or four months, which he said is “pretty good” compared to others.

He thinks part of the solution to reducing disparities requires expanding the size and diversity of the genetics workforce so more patients can be seen.

Geneticists also need to better educate doctors in other fields about when to refer patients, he said. Creating better guidelines would help.

Notably, Black patients in the study were more likely to be evaluated than white individuals for genetic risk factors of cancer — an area where there are clear clinical practice guidelines recommending genetic testing.

They need to come up with similar guidelines for other conditions, such as cardiovascular and kidney diseases, he said.

Another idea he had was to make genetic testing more integrated into standard care in the hospital.

His earlier study found a surprising number of adults in ICUs at Penn had undiagnosed genetic conditions. Such testing is now widely available and often costs as little as a few hundred dollars.

“It costs money, but I think there are cost savings and life-saving interventions that can come from it,” Drivas said.