Wistar Institute scientist Maureen Murphy wants to solve a decades-long mystery: Why is ovarian cancer often resistant to hormone therapy?

In a recently published study, she shared a new theory as to why treatments designed to block or remove hormones, known as hormone therapy, often fail in ovarian cancer — and a potential approach to make them more effective. Such therapies have cut the risk of death from certain breast cancers by a third and reduced the odds of a recurrence by half.

She pinpointed a problem facing hormone therapy — the vast majority of ovarian cancer cases have mutations in a key protein called p53.

Her study, published last month in the medical journal Genes and Development, suggests that mutations in p53, a protein that normally works to stop tumors from growing, drive resistance to hormone therapy and that their effects could be reversed.

Ovarian cancer is notoriously deadly. The most common form of ovarian cancer, high-grade serous ovarian cancer, has an 80% relapse rate after initial treatment and a five-year survival rate of 34%. It’s also highly resistant to immunotherapy.

“There are very few drugs that treat it,” Murphy said.

Her p53 mutation discovery led to her identifying a drug currently in clinical trials that’s promising in a small number of cases. Murphy wants doctors to start testing the combination of the drug and hormone therapy in ovarian cancer.

If the approach makes it into a clinical trial, it would still take years to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the combination. Most treatments tested in clinical trials do not become standard practice.

“For ovarian cancer, the treatment hasn’t changed much in the last 20 years, and so we really do need new treatments,” Murphy said.

How does hormone therapy work?

Hormones are like the body’s mail service.

These chemicals carry messages to cells throughout the body, controlling mood, growth, reproduction, and development.

Tumors can co-opt hormones for their own purposes using proteins called receptors, which act like mailboxes to receive the messages.

Breast cancers, for example, often have estrogen receptors so that they can receive more of a hormone called estrogen. Similar to how bodybuilders use steroids to build muscle, tumors use estrogen to grow and divide.

“Breast and ovarian tumors love estrogen. They grow on it,” Murphy said.

Hormone therapy works by either blocking the receptors from receiving the hormones, or reducing the amount of hormones in the body altogether.

One of the first hormone therapy drugs for cancer, tamoxifen, was approved in the U.S. in 1977 to target the estrogen receptor in metastatic breast cancer.

In this study, Murphy looked at fulvestrant and elacestrant, two anti-estrogen drugs approved for breast cancer.

More than 70% of cases of the most common type of ovarian cancer express estrogen receptors, making them theoretically a good target for hormone therapy, if the p53 problem can be fixed.

Solving the mystery

In her first professor job at Temple’s Fox Chase Cancer Center in 1998, Murphy chose to study the tumor suppressor protein p53, with a focus on genetic variants in women of African and Ashkenazi Jewish descent that put them at risk of cancer.

Decades later, Murphy expanded her focus at Wistar to look at hundreds of genetic variants of the protein found in the general population, in an effort to predict people’s risk of cancer.

Murphy started to wonder whether mutant p53 controlled the function of the estrogen receptor, and how it might affect the response of tumor cells to hormone therapy.

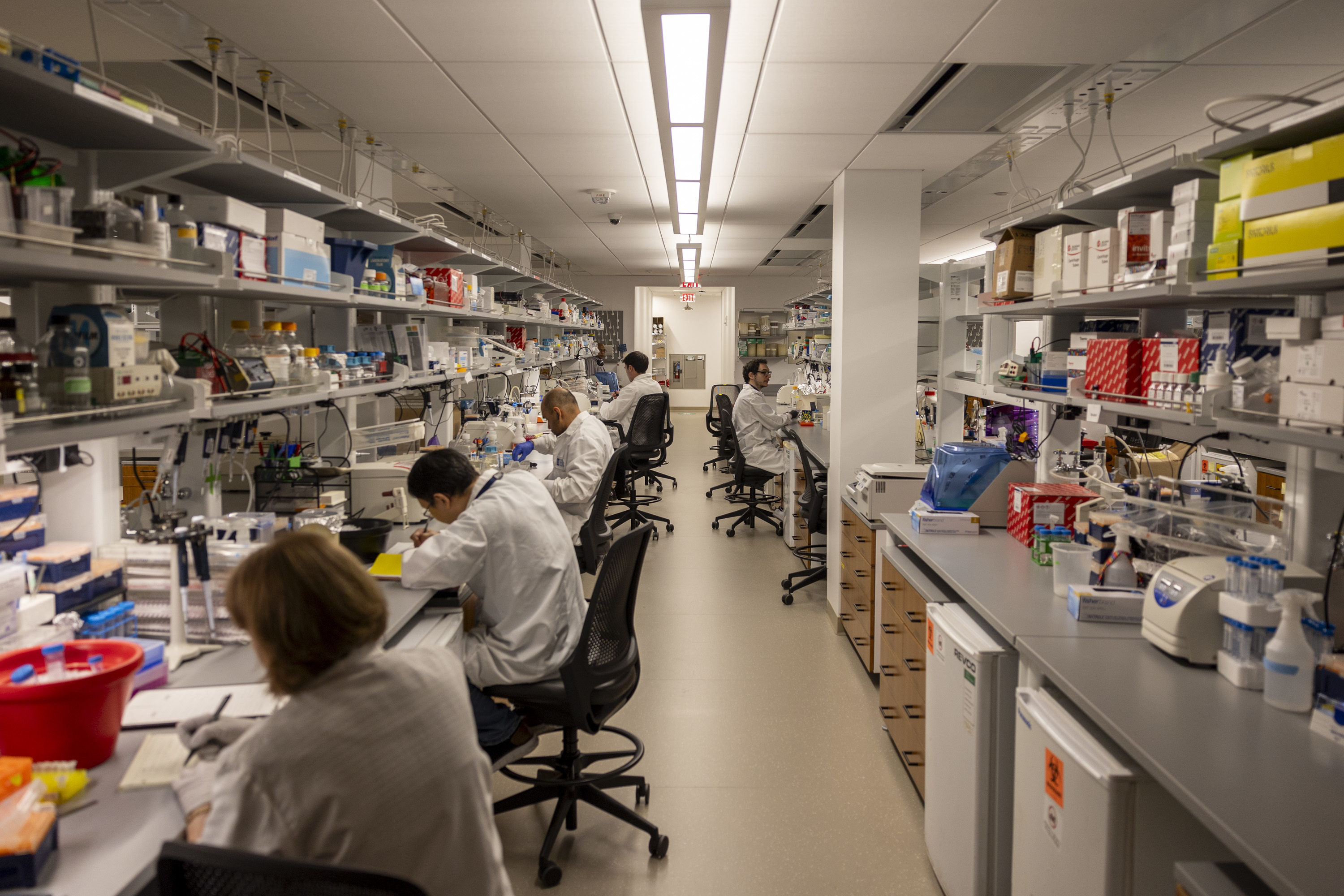

That led her team to look at ovarian cancer because of its high prevalence of p53 mutations. They used cell lines and a lab model to mimic stage 3 and 4 tumors.

The researchers found that when mutant p53 was bound to the estrogen receptor in these models, it inhibited part of the estrogen receptor’s activity, driving resistance to hormone therapy.

By simply removing the mutant protein, tumors “responded great” to the hormone therapy, Murphy said.

Hope for hormone therapy?

While it’s easy to take away p53 in the lab, it’s not as easy in a patient.

There is, however, a promising drug currently being tested in clinical trials. Called rezatapopt, it can convert mutant p53 into a normal-functioning version of the protein.

It works for one particular mutation, Y220C, found in roughly 4% of ovarian cancers.

Murphy’s team found administering rezatapopt alongside hormone therapy led to 75% shrinkage of ovarian tumor models, versus 50% shrinkage when the hormone therapy was given alone.

This finding lined up with rezatapopt’s early data from clinical trials.

“For reasons we didn’t understand, women with ovarian cancer were responding best to this drug,” Murphy said.

Nineteen out of 44 women treated with rezatapopt alone saw their tumors shrink, with one even having a complete response, according to recent interim results from a phase 2 trial.

Murphy hopes this paper will prompt clinical trials to test rezatapopt in combination with anti-estrogen therapy.

However, since rezatapopt only targets one p53 mutation, this approach is limited to a small subset of patients. Murphy hopes that more drugs can be developed that fix other mutant forms of p53 seen in ovarian cancer.

Murphy’s findings make sense conceptually and present a “promising avenue for future clinical trials,” said Tian-Li Wang, the head of the Molecular Genetics Laboratory of Female Reproductive Cancer at Johns Hopkins University, who was not involved in the Wistar study.

A caveat is that the study looked at a limited number of cell lines, she said.

She thinks the results should be confirmed in cases of ovarian cancer that have other types of p53 mutations to see if it could be applied more broadly.

“[I’m] really interested to see if the approach can benefit patients,” Wang said.