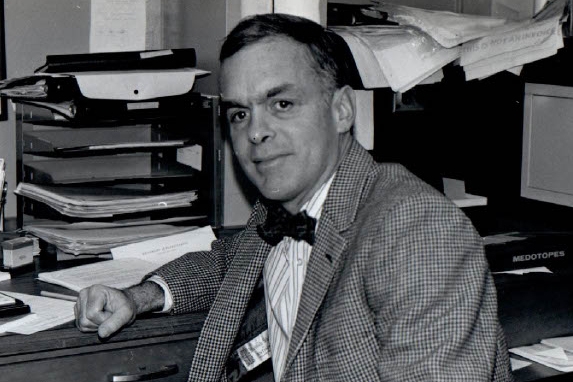

William L. Elkins, 93, of Coatesville, pioneering research immunologist at what is now the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, associate professor emeritus of pathology and laboratory medicine, innovative longtime Angus cattle rancher in Chester County, avid sailor, and veteran, died Tuesday, Nov. 11, of complications from pneumonia at Chester County Hospital.

The great-great-grandson of Philadelphia business tycoon William Lukens Elkins, Dr. Elkins fashioned his own distinguished career as a scientist, medical researcher, and professor at Penn from 1965 to 1985, and owner of the Buck Run Farm cattle ranch in Coatesville for the last 39 years.

At Penn, Dr. Elkins conducted pioneering research on how the human immune system fights infection and disease. He collaborated with colleagues in Philadelphia and elsewhere around the country to provide critical new research regarding bone marrow transplants and pediatric oncology.

His work contributed to new and more effective medical procedures at Penn, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and elsewhere, and he instructed students and residents at Penn. But his lifelong love of the fields and rolling hills he roamed as a boy in Chester County never faded, he told Greet Brandywine Valley magazine in 2023.

“Farming is in my blood,” he said. “So even when I went to medical school and all that, the enthusiasm never left, and I wanted to go back to it.”

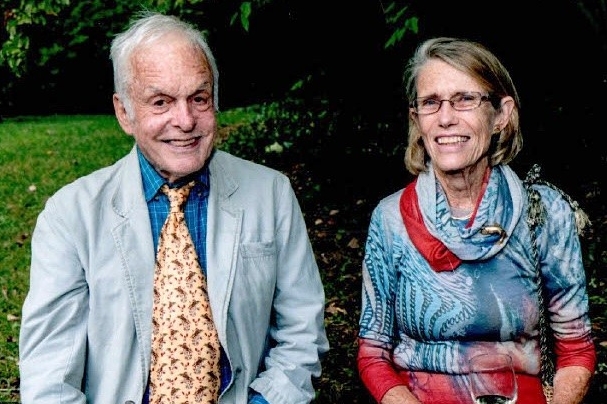

So he retired from medicine at 53, and he and his wife, Helen, bought nearly 300 acres of the old King Ranch on Doe Run Church Road in Coatesville. She kept the books and looked after the business. He became an expert on breeding cattle and growing the high-energy grass they eat.

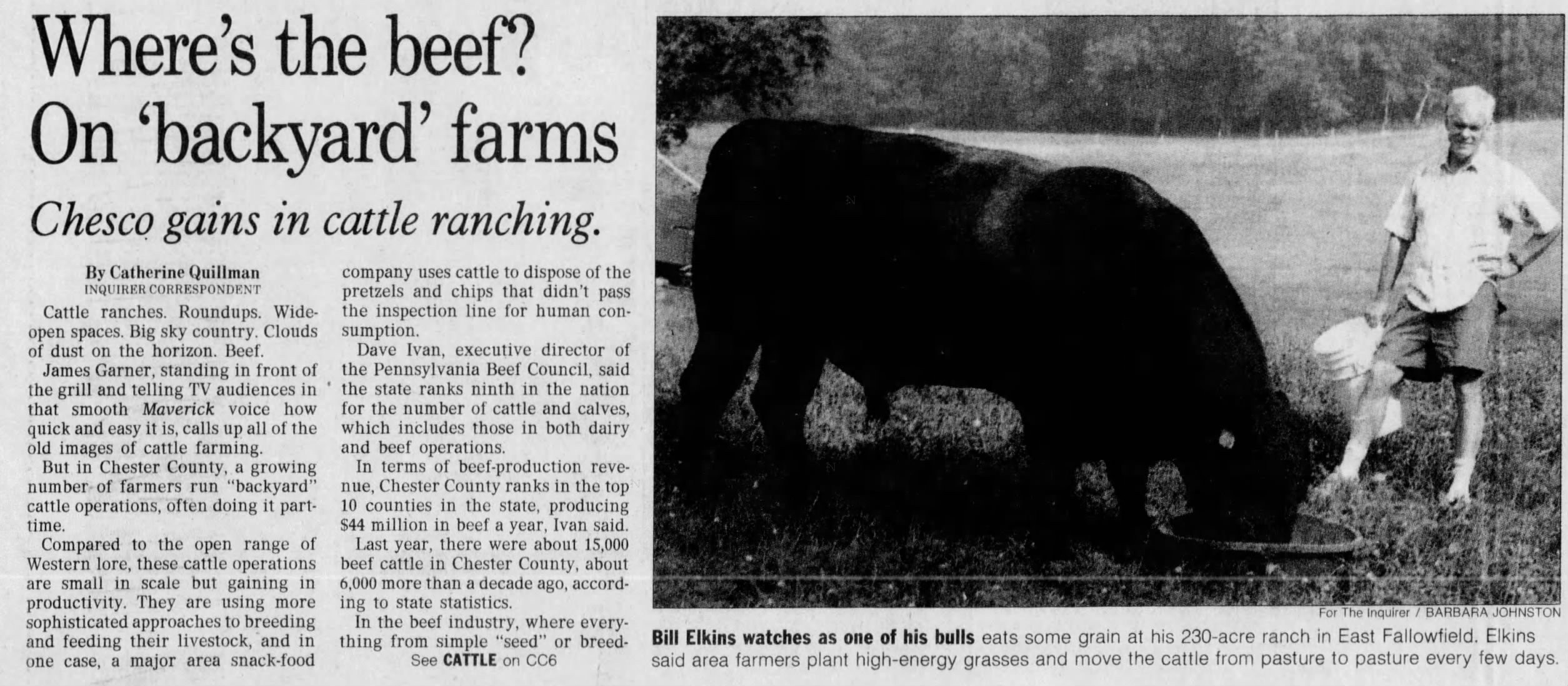

Wearing floppy hats and riding a colorful ATV from field to field, Dr. Elkins worked his land for decades. He mended fences and tended daily to his 120 cows, heifers, and prize bulls.

He championed holistic regenerative farming and used new scientific systems to feed his cattle. He rejected commercial fertilizer and knew all about soil composition, grass growing, and body fat in cattle.

In a 1995 Inquirer story, he said: “Cattle are just like anyone else. If you just turn a few cattle out in a great big field, they will wander around, eat the grass they like best, and leave what they don’t want. That means the less desirable grasses tend to predominate.”

He traveled the country to confer with other cattlemen and helped found the Southeast Regional Cattlemen’s Association in 1994. He sold his beefsteaks, patties, jerky sticks, and kielbasa grillers to private customers online and to butchers and restaurants.

At least one local chef featured an item on the menu called Dr. Elkins’ Angusburger. Lots of folks called him Doc.

He earned his medical degree at Harvard University in 1958 and served two years in the Navy at the hospital in Bethesda, Md. He was a surgical intern in New York and discovered that he preferred the research lab. Before Penn, he worked at the Wistar Institute of biomedical research.

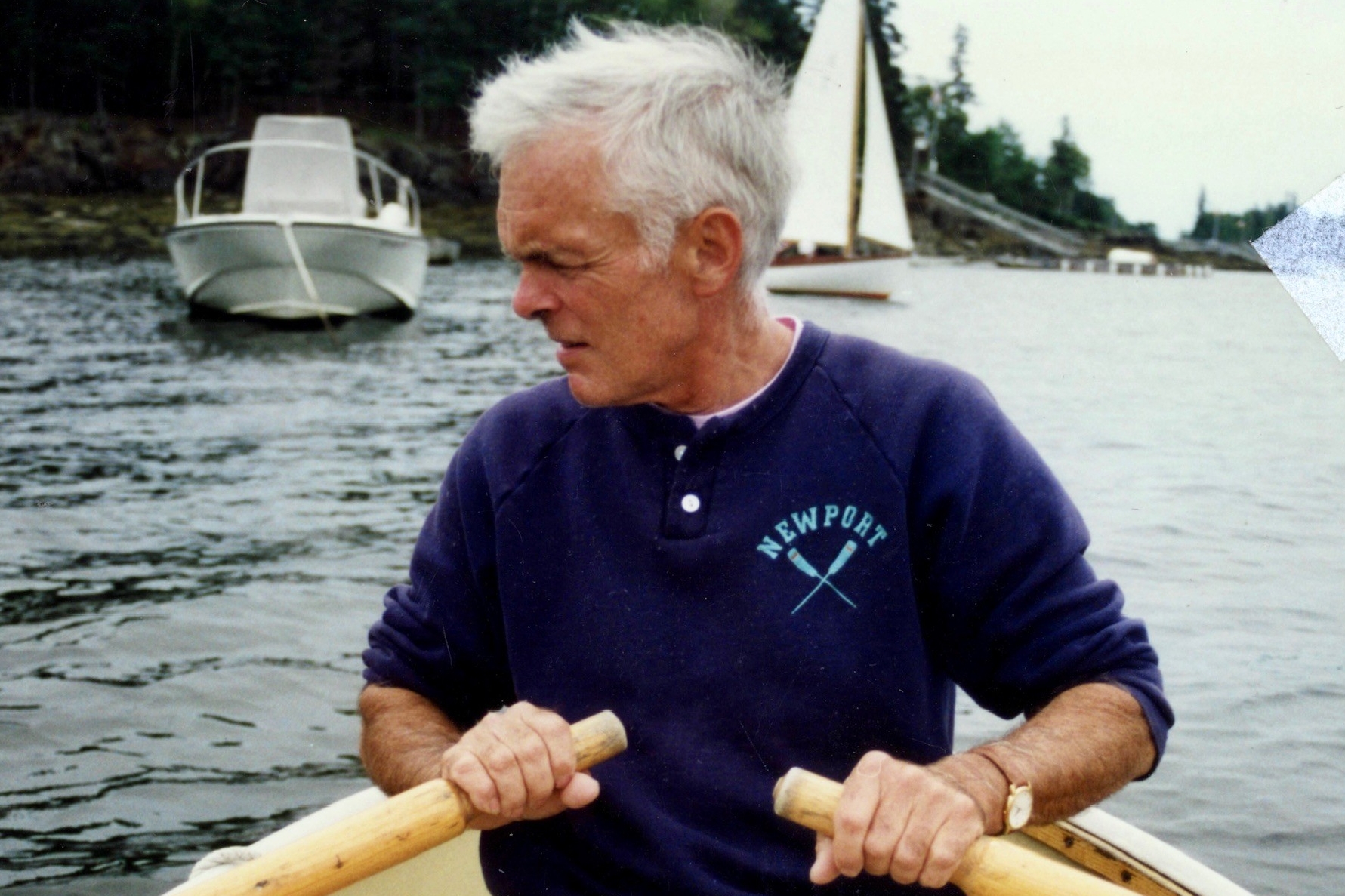

Away from the lab, Dr. Elkins was an ocean sailor, expert navigator, and former boat club commodore. He was active with the Brandywine Conservancy, Natural Lands, and other groups, and was lauded by national organizations for his wide-ranging conservation and wildlife efforts.

He made his farm a haven again for the bobolink grassland songbird and other migratory birds and butterflies that had dwindled. “Buck Run Farm is more about growing grass and trees than beef,” he told Greet Brandywine Valley. “We’re blessed by the land.”

William Lukens Elkins was born Aug. 2, 1932, in Boston. He lived on the family dairy farm in Pocopson, Chester County, when he was young, went to boarding school in Massachusetts for four years, and earned a bachelor’s degree in biology at Princeton University.

He met Helen MacLeod at a party in Washington, and they married in 1966 and had a daughter, Sheila, and a son, Jake. They lived in Center City, Society Hill, and Villanova before moving to the farm. “He was easy to be with,” his wife said.

Dr. Elkins loved nature, fishing, and baseball, and he followed the Phillies, the Flyers, and other sports teams. “He had a wonderful bedside manner,” his daughter said. “He was a great listener. He really knew how to support people.”

His son said: “He was unassuming and direct. He spoke his mind. He connected with so many different people. He was curious about the world around him.”

His wife said: “He was thoughtful and always concerned about people. He had good humor. He was fun.”

In addition to his wife and children, Dr. Elkins is survived by five grandchildren and other relatives. A sister died earlier.

A celebration of his life is to be held later.

Donations is his name may be made to the Stroud Water Research Center, 970 Spencer Rd., Avondale, Pa. 19311.