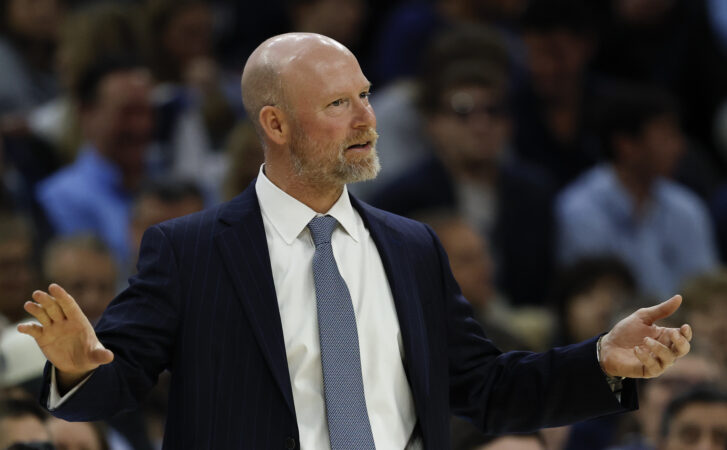

Matt Campbell completed his first recruiting class as the head football coach at Penn State, and the team welcomed 55 newcomers, including 15 recruits in the class of 2026, four of whom put pen to paper on national signing day.

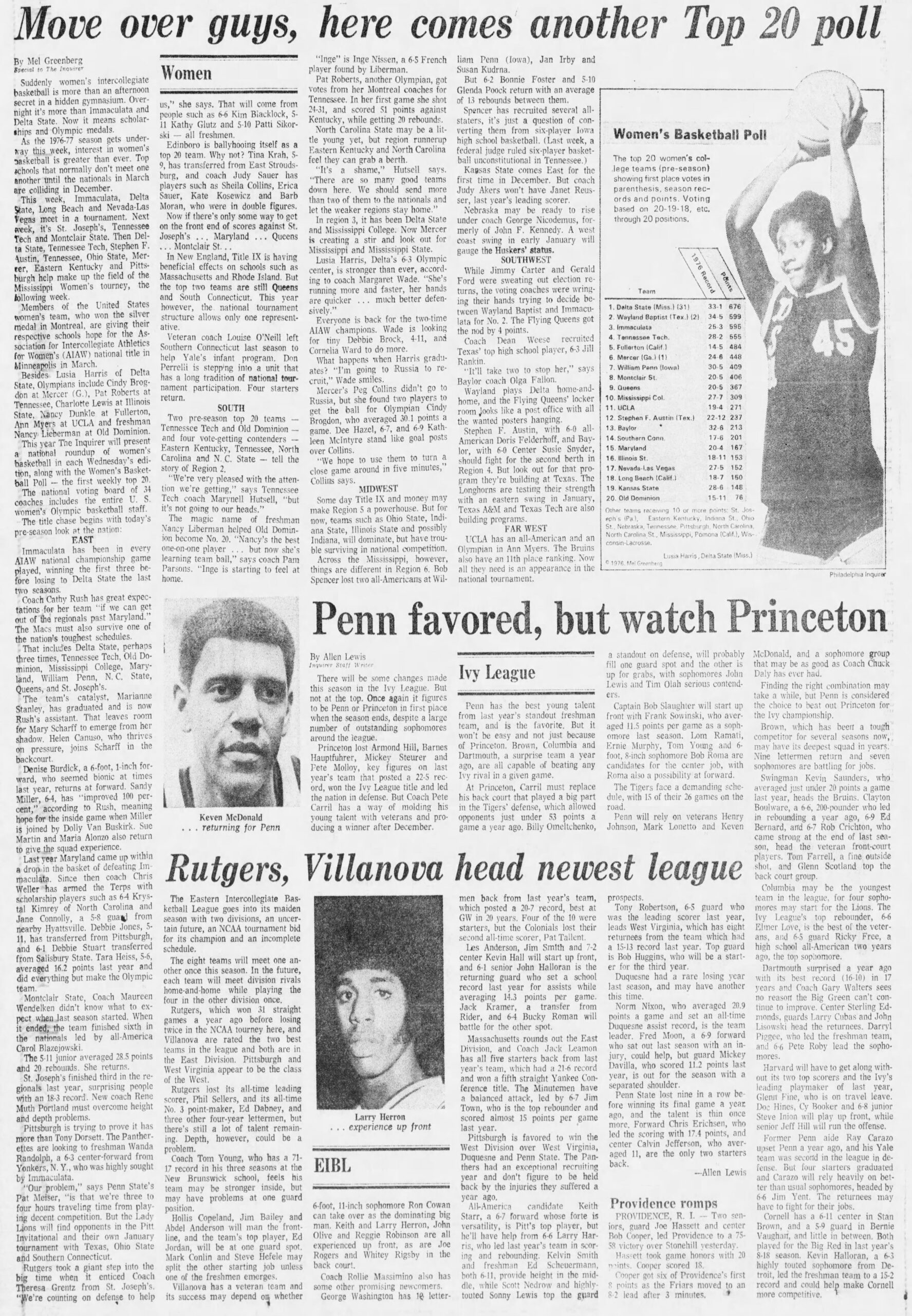

Penn State’s class is ranked No. 41 nationally and No. 10 in the Big Ten, according to 247Sports. Many of the players in Campbell’s class were signed before Wednesday’s national signing day. He landed 40 players from the transfer portal, 24 of whom came from Iowa State.

“I feel like we went with a mentality of not wavering from who we want this football team to be,” Campbell said at a news conference. “Young men that love the sport of football, young men that love Penn State, and I would say, most importantly, young men also that know, they understand the value of an education from this institution. Those core values were really critical for us to kind of build this football team forward.”

2026 class

Penn State’s class took a hit during the early signing period while the program continued its search for a head coach. Eleven pledges flipped to Virginia Tech to join James Franklin. Malvern Prep edge rusher Jackson Ford and Nazareth’s Peyton Falzone, a three-star quarterback, were the only two to sign early with the Nittany Lions.

Since then, Penn State had an additional nine recruits sign, and each of Wednesday’s signees, which included Elijah Reeder, Keian Kaiser, Pete Eglitis, and Lucas Tenbrock, were originally committed to play for Campbell at Iowa State.

Reeder, a Bayville, N.J., native, is a four-star edge rusher and the fourth-best prospect in New Jersey, according to 247Sports. In his senior season at Central Regional High School, Reeder recorded 50 tackles and eight sacks. Reeder is listed at 6-foot-6 and 210 pounds.

The defensive lineman’s other FBS offers came from Iowa State and Missouri.

Eglitis, an offensive lineman, is from Columbus, Ohio. The three-star 6-7 prospect earned all-Ohio honors in 2024 and 2025, as he helped lead Bishop Watterson High School to back-to-back state championships. In addition to flipping from Iowa State, Eglitis also chose Penn State over Louisville, Georgia Tech, Kentucky, and Missouri, among others.

Kaiser is a linebacker from Sidney, Neb. The three-star recruit was a multisport athlete at Sidney High School, participating in the high jump and the discus. In his junior year, the 6-4 Kaiser recorded 127 tackles and two interceptions.

A native of St. Charles, Ill., Tenbrock is the sixth-best punter in this year’s recruiting class, according to the composite rankings of ESPN, Rivals.com, and 247Sports. Tenbrock’s only offer came from Campbell at Iowa State.

While most of the four- and five-star recruits are already committed to schools by national signing day, Penn State was on the losing end of one recruiting battle on Wednesday. The Nittany Lions made a late push to persuade Samson Gash to come to Happy Valley instead of Michigan State, but the four-star wideout and Michigan native chose to stay closer to home.

Ford is the only Philadelphia-area talent in the class of 2026.

Transfers

The majority of Penn State’s roster in 2026 will be transfers.

Campbell signed 40 players from the portal. The Nittany Lions likely will need the veteran presence, as they lost 47 members of last year’s team to the portal after finishing 7-6 and firing Franklin in the middle of the season.

Ethan Grunkemeyer perhaps was the most impactful of the outgoing transfers. Grunkemeyer took over after starting quarterback after Drew Allar suffered a season-ending ankle injury in October. Grunkemeyer, who passed for 1,339 yards and eight touchdowns in 2025, followed Franklin to Virginia Tech.

Campbell turned to a familiar player to fill the hole at quarterback in Rocco Becht.

Becht spent three seasons as the starter under Campbell at Iowa State. He logged two 3,000 passing-yard seasons and chose to follow his old coach for his final year of eligibility.

“What I believe Penn State football is — integrity, character, class, excellence, grit — [Becht] embodies every one of those traits,” Campbell said. “And so to me, I just felt like that was such a critical opportunity for him to finish his career with us.”

Becht is not the only former Cyclone expected to have a major impact.

Benjamin Brahmer, a 6-7 tight end who led the Cyclones with 37 catches and six touchdowns last season, will spend his senior season at Penn State. The Nittany Lions also will get Brett Eskildsen and Chase Sowell, last year’s leading receivers at Iowa State. They finished with 526 and 500 yards, respectively. Campbell added the Cyclones’ leading rusher, Carson Hansen (952 yards on 188 carries), to the roster as well.

The Nittany Lions hope the veteran Cyclones can replace the offensive production they lost after running backs Kaytron Allen and Nick Singleton declared for the NFL draft.

“[Hansen is] durable, he’s tough, he’s physical,” Campbell said. “He’s got great vision. He’s got the ability that if you need him to carry the ball 40 times in a game, he can do it. … And so I think what you’ll get from Carson is a guy that’s about as trusted as you’re going to find.”

Former Cyclones will also impact the defensive side. Campbell landed Iowa State’s leading tacklers in Marcus Neal, a junior defensive back, and Kooper Ebel, a senior linebacker. Both finished last season with 77 tackles, with Neal adding a team-high 11 tackles for loss and two interceptions.

Caleb Bacon, a redshirt senior linebacker who led Iowa State with three sacks last season, also will join Penn State.

While the number of transfers who followed Campbell to Penn State from Iowa State should provide Campbell some proven talent, the first-year coach noted that players will still have to navigate change to be successful in Happy Valley.

“I think there’s competition and there’s the ability to grow, but we’ve got to go grow,” Campbell said. “Every coach in America is going to tell you how great their team is. I’m saying the opposite. We’ve got really great talent, but we’ve got to grow forward. We’re all going through change. We have to figure out who can do it the most consistently.”