“Heaven … I’m in heaven … and my heart beats so that I can hardly speak.”

Harry Barlo, in a crisply tailored black suit, bronze tie, and matching pocket square, bopped jauntily to the Fred Astaire standard, his quartet swinging effortlessly behind him, the crowd nodding and foot-tapping.

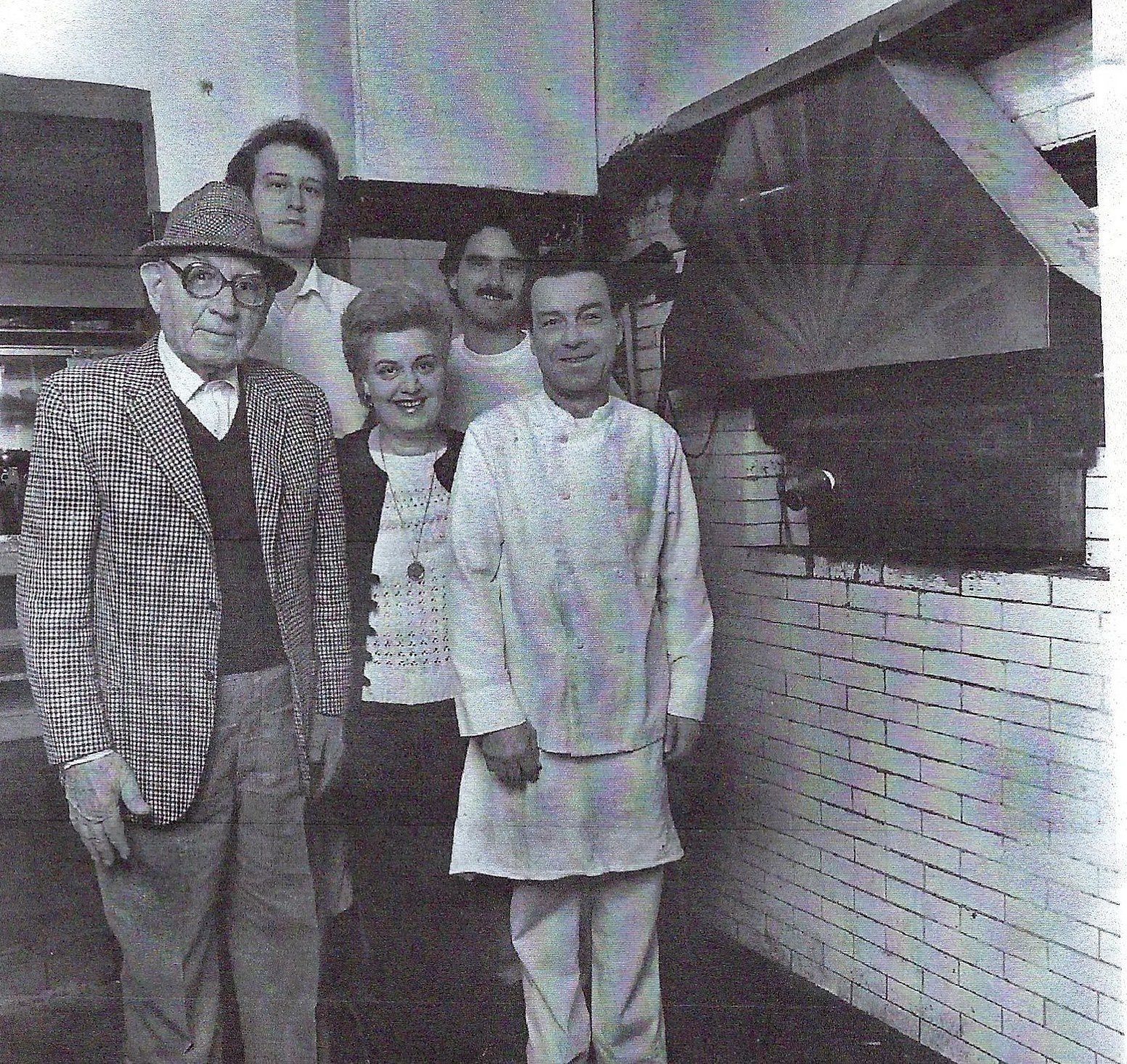

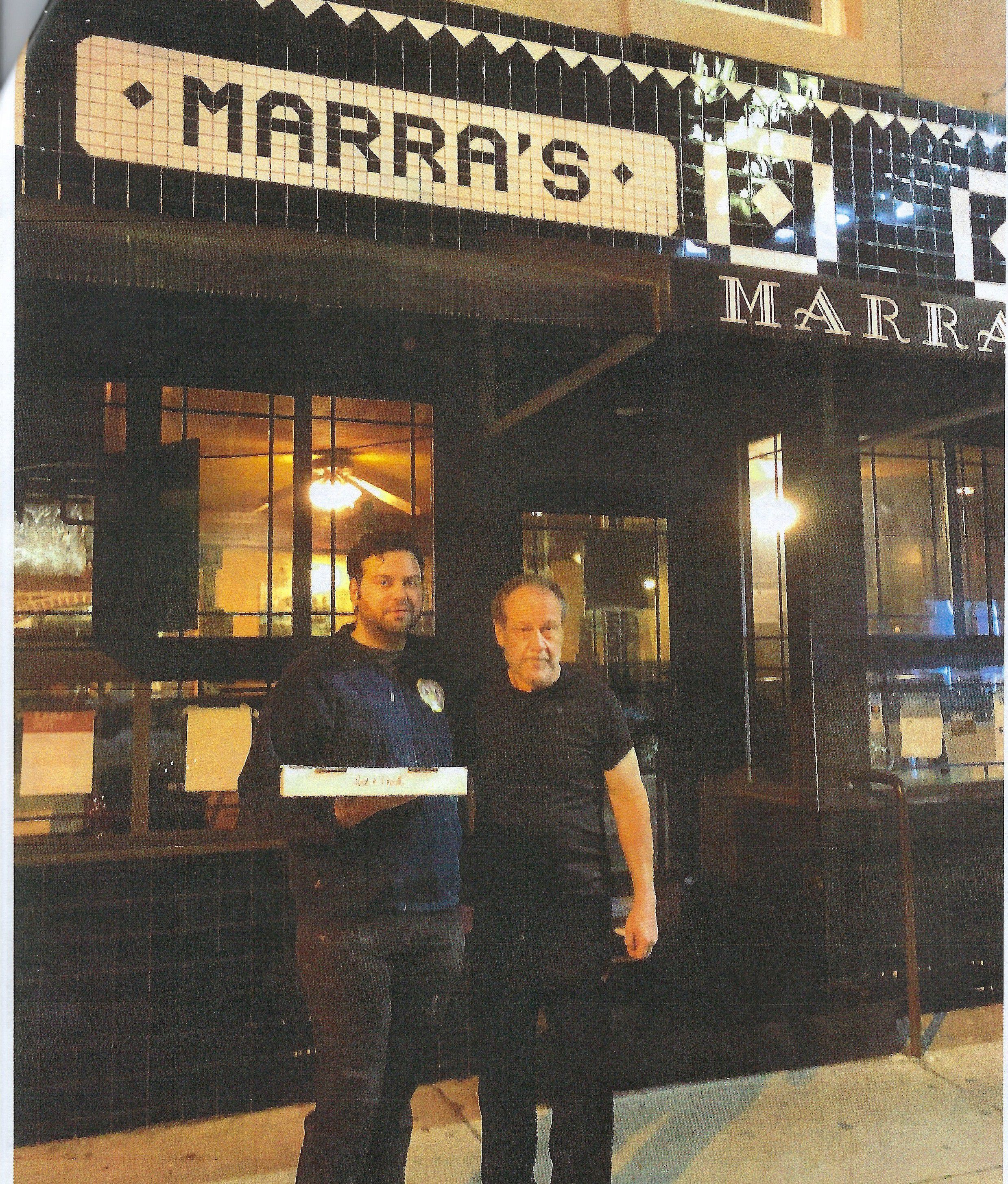

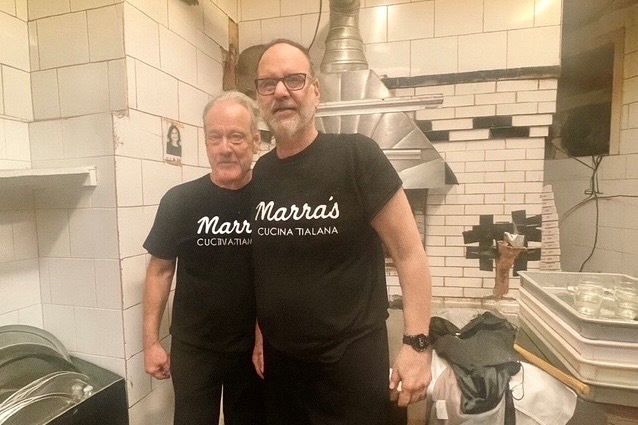

At that moment — for a moment, anyway — Franco Borda’s right knee quit acting up. Beaming from the back of his revived High Note Caffe in South Philadelphia, Borda took it all in: 64 people dressed up for a Saturday night out, sitting in his restaurant, eating his eggplant rollatini and his son Anthony’s pizza, enjoying live music.

“You see this?” he said in amazement.

Borda, 64, wants to create the sort of supper club that barely exists anymore — intimate, aimed at a boomer audience, with drinks and an informal menu.

It’s an all-new act for the High Note — an update on Borda’s previous restaurants at 13th and Tasker over the last 35 years.

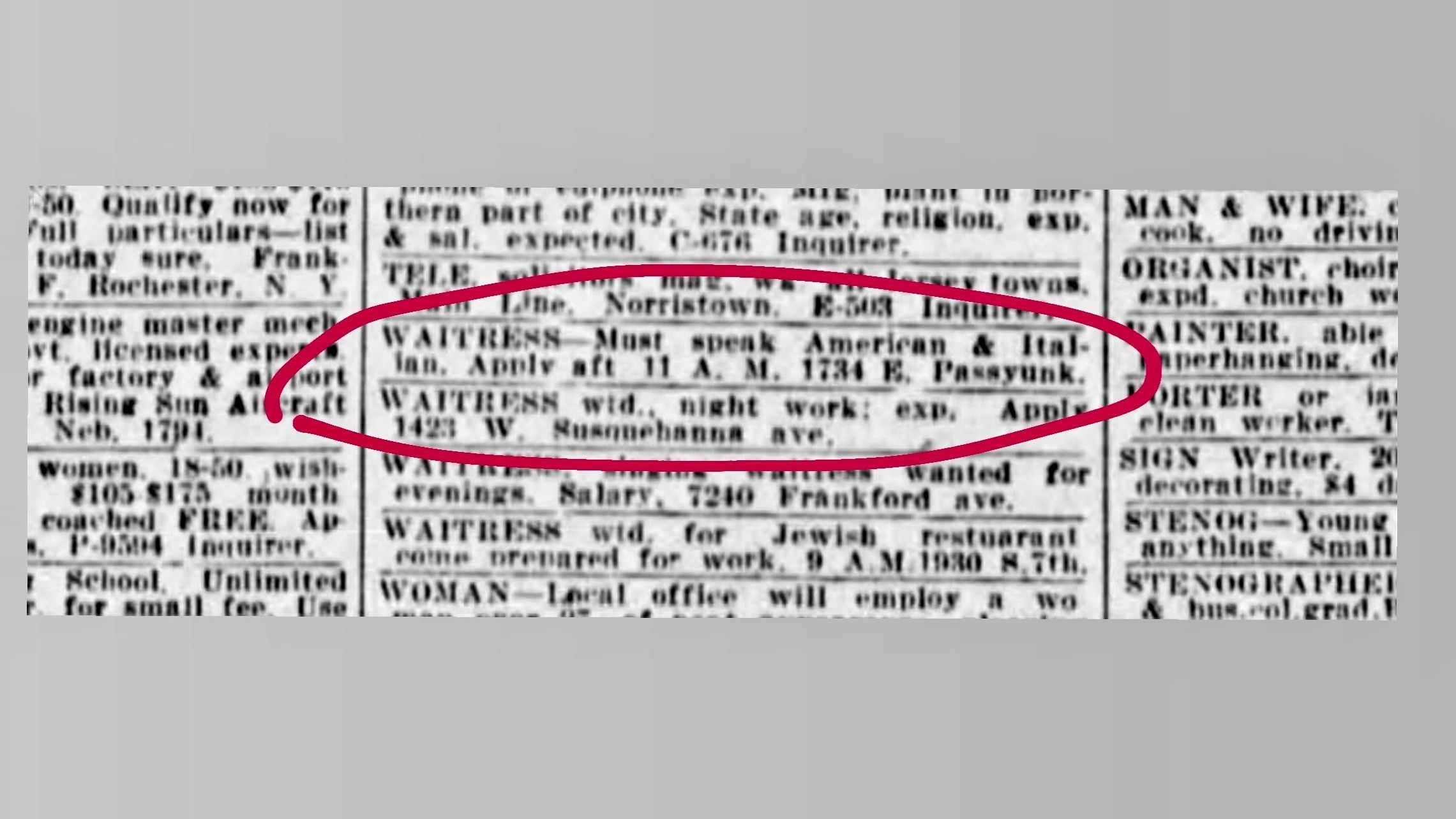

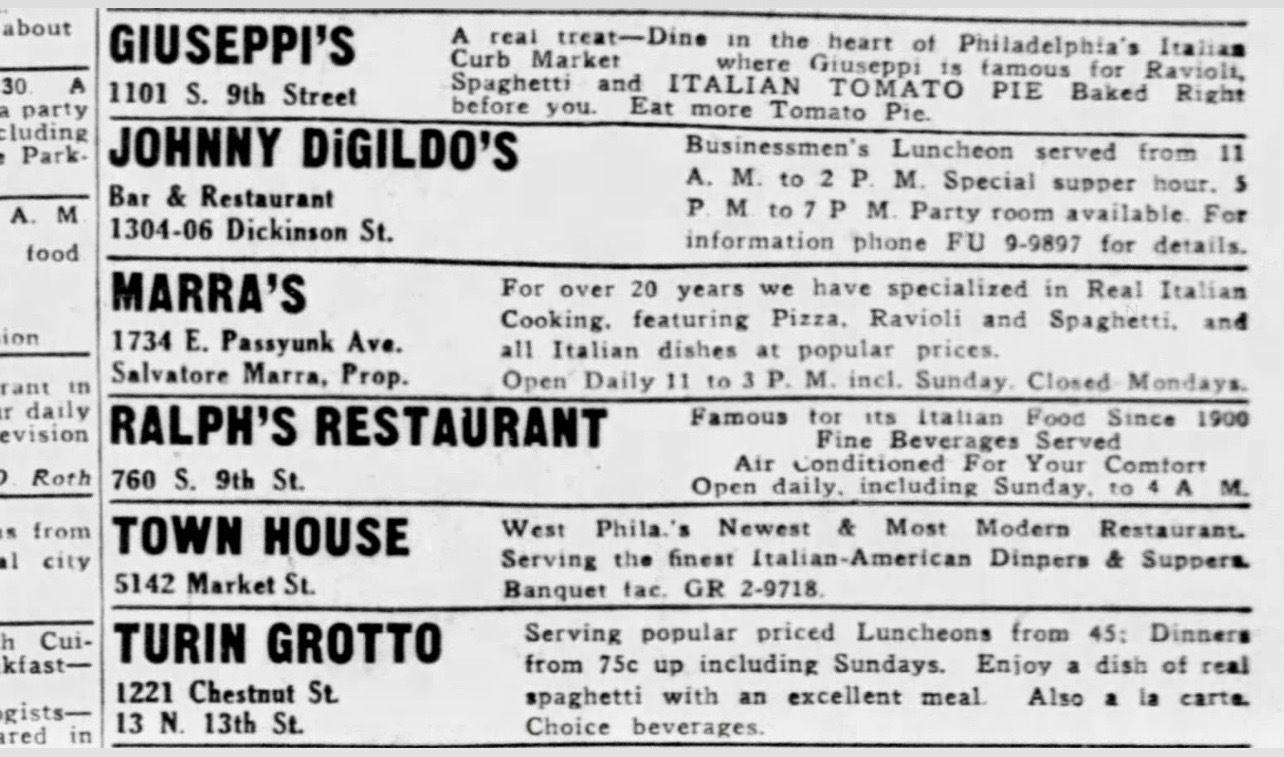

Borda, who grew up three blocks away, has been singing opera all his life. In the days he ran Francoluigi’s with his former business partner, he would pop out from the stove to sing an aria, and he’d bring in other amateur singers. Sometimes, Phil Mancuso, who owned Mancuso’s cheese shop, and Frank Munafo, a nearby butcher, would show up, and they’d bill themselves as the Butcher, the Baker & the Cheesemaker.

Over the years, however, Borda found that younger diners were less interested in opera overtaking their meals. He switched gears at High Note Caffe. Jazz stayed, but opera became occasional.

In March 2020, when the pandemic shut down the High Note and other restaurants at the outset of the pandemic, Borda stepped back altogether. He hired an engineer and an architect, removed a wall, expanded the room, slid the kitchen back, and secured assembly and entertainment licenses.

His wife, Teresa, said she thought he was crazy. “You need knee surgery,” she reminded him.

Borda countered: “I got 10 more years in the kitchen, you know, and I love it.”

In 2022, Borda’s son Anthony — who started making pizzas with his pop while in kindergarten — opened Borda’s Italian Eats, a walk-up shop on the Tasker Street side of the property (now closed). That was a temporary setup until the rest of the place could be finished.

“I really wanted to focus on the entertainment,” Franco Borda said. “We want to give people a place in South Philly where you can sit down and enjoy some jazz and eat a little bit and not get banged over.”

Ticket prices vary but are reasonable. It’s $25 for the Dec. 12 show by the Jack Saint Clair Quartet. All told, you’re looking at a date night for just over $100, with a pizza ($20 or $25), a plate of mussels red ($18.95), $15 cocktails (White Russians! Sloe Gin Fizzes!), and a $7 tiramisu you should not miss.

“I’m not doing this as a business,” Borda said.

That much is clear. For now, he is booking only about two shows a month, with tickets sold online and no walk-ins. After the Jack Saint Clair show, vibraphonist Tony Micelli will perform on Dec. 13. On Jan. 30, George Martorano — who served 32 years in federal prison for a drug conviction before his release in 2015 — will do a one-man show to talk about his time in custody.

Borda said the idea is to not run a conventional restaurant again, rather to provide a venue to musicians who rarely get a platform.

Eventually, when Borda’s knee gets straightened out, he said he wants to get himself back into vocal shape, get up on stage, and do some opera.

For now, he said, “I want to find some tenors and sopranos who want to be exposed and come out and sing their [hearts out].”

People like Harry Barlo.

Barlo — born Harry Schmitt — spent 21 years on the Philadelphia police force before retiring in 1992. All the while, he sang in clubs. “I balanced show business and my other jobs because I had to eat,” he said.

Twenty years ago, in his early 50s, he chased his dream and moved to Las Vegas, where he sang in a doo-wop group in casino lounges before switching to the Great American Songbook under the nom de croon Golden Voice Harry.

“Las Vegas — that was the dream of a lifetime,” he said. ”Show business is a tough business. It only fed me for a while.” After returning to Philadelphia, he got into recording and, later, streaming, he said.

Barlo said he had gigs lined up before COVID-19 dried up live music. Now a casino compliance representative with the Pennsylvania Gaming Control Commission, he said he thought his performing days were over. Then he heard from Benny Marcella, a friend of Borda’s.

Barlo said he was initially unsure about playing at High Note. “Benny said, ‘Go down and look at the place.’ So I met Franco, we talked, and Franco said, ‘Why don’t you stand on the stage and see what you think.’ When I stood on that stage, he had me. That’s the perfect room for me. I like working in an intimate setting.” Marcella helped round up the musicians, and it was showtime.

“Are the stars out tonight? I don’t know if it’s cloudy or bright. I only have eyes for you, dear…”

Ken Moyer nailed his sax solo, backed by Bill Tesser on drums, Marty Mellinger on piano, and Steve Varner on bass. Barlo’s eyes swept the room. His kids were there, watching with their friends. “I first saw him perform when he sang to me for my 16th birthday,” said his stepdaughter Danielle DeAngelis. “And all these years later, it never gets old. He’s still amazing.” He dedicated “I’ve Gotta Be Me” to her.

Barlo, who is booked at the High Note for Valentine’s Day, said High Note reminded him of the rooms at the Sahara and the Stardust. “They were intimate lounges,” he said. “I’m an old-style guy — you get a lot of feedback from the audience when you’re close to them. A friend of mine who was there that night said, ‘Harry, you finally found your niche.’ He’s right. Franco’s got a great idea, and I hope it works.”