One woman moved back across the country to care for her grandmother, giving up her dreams of sunshine and palm trees. A young mother, overwhelmed caring for two children and her ailing grandmother, finally asked family to help her juggle. And another woman assumed financial responsibility for her grandmother after her home fell into foreclosure.

All three women belong to what aging experts call America’s unseen workforce — the 48 million family caregivers who provide unpaid support that allows millions of adults who are older, ill, or disabled to remain at home. It is a group that is expected to shoulder even more responsibility as the population ages and conditions such as dementia, cancer, and heart disease continue to rise. Within the already stretched community of caregiving, they belong to a group that is even more overlooked and undercounted: grandchildren.

Research shows unpaid caregiving is valued at more than $1 trillion, said Nicole Jorwic, chief program officer at the nonprofit Caring Across Generations.

“Right now, families filling in the gaps is the only option for a lot of people whether they’re grandchildren or not,” said Jorwic, who is in her 40s and helping care for three grandparents in their 90s.

Research suggests race and ethnicity may be the “strongest predictors” of who becomes young adult caregivers, with about a third of caregivers in Asian, Black, or Latino families being 18 to 34 years old. And family caregivers generally are more likely to be women.

Caring for an aging family member is already an emotional, financial, and physical gantlet. Add to that the inexperience of youth, and some aging researchers say the challenges for grandchildren who are caregivers become even harder to navigate.

What this looks like in real life — the exhaustion, the sacrifice, the sense of purpose — comes through in the stories of three women shouldering the weight, not simply out of necessity but also devotion.

A caregiver who built an online community

The average caregiver is 51 years old. But five years ago, Elaine Goncalves stepped into the role at 28. She hadn’t imagined becoming her grandmother’s caregiver. Elaine’s high-paying tech job had just allowed her to relocate to San Diego.

Her grandmother, Adelaide Goncalves, was 90 and living in Massachusetts with one of her daughters and a different grandchild, barely able to manage the stairs of her third-floor home. Before Elaine left for California, she tried in vain to relocate her grandmother, asking all six of Adelaide’s surviving children for help. Elaine’s parents, unsure if their work schedules would accommodate the need, agreed with her plan, and her grandmother did, too — until it was time to go.

“Other family members were telling her not to,” Elaine said.

When the pandemic hit, Elaine was forced to return home. The way she made peace with the move was by finding a way to care for her grandmother. She kept the plan quiet, afraid relatives would talk her grandmother out of it again, and mindful of how it might look for a granddaughter to take on a role traditionally expected of a daughter in her Cape Verdean family. When someone in the house got COVID, no one objected to Adelaide relocating.

The first two years were “pretty humbling,” Elaine said. “I experienced crazy things like walking in my bathroom and it was covered in poop,” she said. “I basically went from ‘She’s so sweet!’ to praying — literally — every day for patience.”

The experience also made Elaine realize she owed her aunt an apology for judging the care she had provided and the frustration her aunt expressed in taking on a formidable task.

What the family didn’t know then was that Adelaide had dementia. Elaine said guilt set in. A caseworker who called unexpectedly to schedule her grandmother’s annual physical helped secure the diagnosis, she said, and connected Elaine with “resources I needed but didn’t know were available.” Home health aides now feed, bathe, and change her grandmother, who goes to an adult day program daily.

In 2020 and 2025, about 18% of family caregivers ages 18 to 49 were caring for their grandparents, according to reports by AARP and the National Alliance for Caregiving. But researchers say it’s hard to know exactly how many young people provide care because the term “caregiver” can be defined in so many ways and national surveys count differently.

Researchers say that many young people aren’t identified because unlike Elaine, they’re not the primary caregiver, but rather pitching in as part of a family network.

“Most of them are disrupting parts of their life to engage in something they may not be counted as doing,” said Karen Fingerman, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin and director of the Texas Aging and Longevity Consortium.

Last year, Adelaide’s heart briefly stopped, a scare that led to hospice care.

“Emotionally, this has been a roller-coaster ride,” Elaine said. “Balancing the family dynamics and their help — or lack thereof — and their opinions and the emotions of her being hospitalized and me thinking she’s dying” forced tough family conversations.

Elaine decided to reflect on her experiences a few months ago, and wound up sharing the lessons online, inadvertently building a community through the social media series. It has drawn 1.6 million views, thousands of comments and shares, and more messages than she can keep up with — and she had posted only 11 of the 15 lessons.

“I didn’t know there were other people my age dealing with this,” she said.

A caregiver who had to give up care

Ramona Reynolds didn’t go away to college, opting instead to stay home and care for the grandmother who raised her. They had never spent more than a weekend apart, including after the 38-year-old got married and started having children. But eventually her 86-year-old grandmother’s health deteriorated beyond Reynolds’s capacity to provide care.

“That was a hard pill to swallow,” she said of sending her grandmother, Thelma McDonald, to live with her aunt.

For years, Reynolds watched dementia transform the woman who once commanded so much respect in their Brooklyn neighborhood that boys on the block carried her groceries upstairs unasked.

Reynolds was in her 20s when her grandmother was first diagnosed with dementia. A friend noticed that her grandmother was repeating herself. A few years later, one of her great-uncles did, too. Even though McDonald has four living children and a host of brothers and sisters, Reynolds never thought to ask them for help.

For years, things were manageable. Then, Reynolds got pregnant with her second child, and the family decided to relocate to Georgia for more space. As they prepared to move, Reynold’s family stayed with her in-laws and was to become a paid family caregiver. What she didn’t know was that moving someone with dementia out of a familiar environment can worsen their symptoms.

“So, when we moved here, I’m like, ‘Oh my god. Why is it so much harder?’” she recalled of her grandmother, who worked as a paid caregiver after emigrating from Jamaica. Reynolds was chasing after a toddler, trying to make sure her son — who is autistic, has ADHD, and in virtual school – stayed on task, all while also caring for her grandmother. “We did everything for her. Cooking, bills, dealing with doctors, social workers, program directors, all that stuff.”

Being a caregiver can be draining mentally, physically, and emotionally, experts say. What ultimately drives caregiver burnout and makes the role heavy is the lack of support, recognition, and resources, and the isolation, more so than the work itself, said Melinda S. Kavanaugh, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee whose research focuses on children and young adult caregivers.

“You can only do something on your own without any support for so long before you break,” she said, noting that older caregivers “might be able to last a little bit longer” because they have life experience to draw on.

Reynolds knew something had to give as her grandmother’s condition progressed and McDonald began unlocking doors trying to leave. She called a family meeting and asked for help. Her aunt stepped in, taking over her grandmother’s care.

“It’s a hard balance,” Reynolds said. “On the one hand, I would be nothing without this woman. But on the other, now I have my own family, and these babies deserve a mother that’s whole, that is not filled with anxiety and grief and a little bit of resentment, too.”

A caregiver shouldering financial responsibilities

Sharita Payton, 45, stepped in to help her sister care for their grandmother about two years ago, when several crises hit at once. Their grandfather died, their grandmother became more forgetful, maintaining the house became unaffordable, and her sister was facing personal struggles.

Payton’s mother was unable to take on the responsibility full time because she’s caring for a husband who has had multiple strokes. Neither could her grandmother’s other children, for different reasons: One is in jail, another struggles with addiction issues, and the third lives far from the family in South Carolina.

“There’s a lot of different nuances involved,” she said. “To look around and see that after everything they have given, there’s really no one that’s available to pour back into her when she needs it. That’s been really hard to navigate. I just had to step up.”

So, on and off for the past two years, Payton’s husband would drive her 89-year-old grandmother, Geneva Madison, between their house in Massachusetts and her mother’s house in Connecticut. Payton became her grandmother’s power of attorney, took over her finances, and began setting aside money for when a move was needed. That move came several months ago when she set her grandmother and sister up in a new apartment.

Caregiving can be financially stressful for families because close to three-quarters of costs are out of pocket, said Sue Peschin, president and CEO of the Alliance for Aging Research. Often families don’t realize this “until they’re up against it,” she said, noting that people tend to think Medicare covers long-term care and it doesn’t.

Part of the misconception is how “we think about retirement in the United States,” Peschin said. “Oftentimes the thinking is, ‘How do we want to live as fully functional human beings?’” But not what happens after a health crisis.

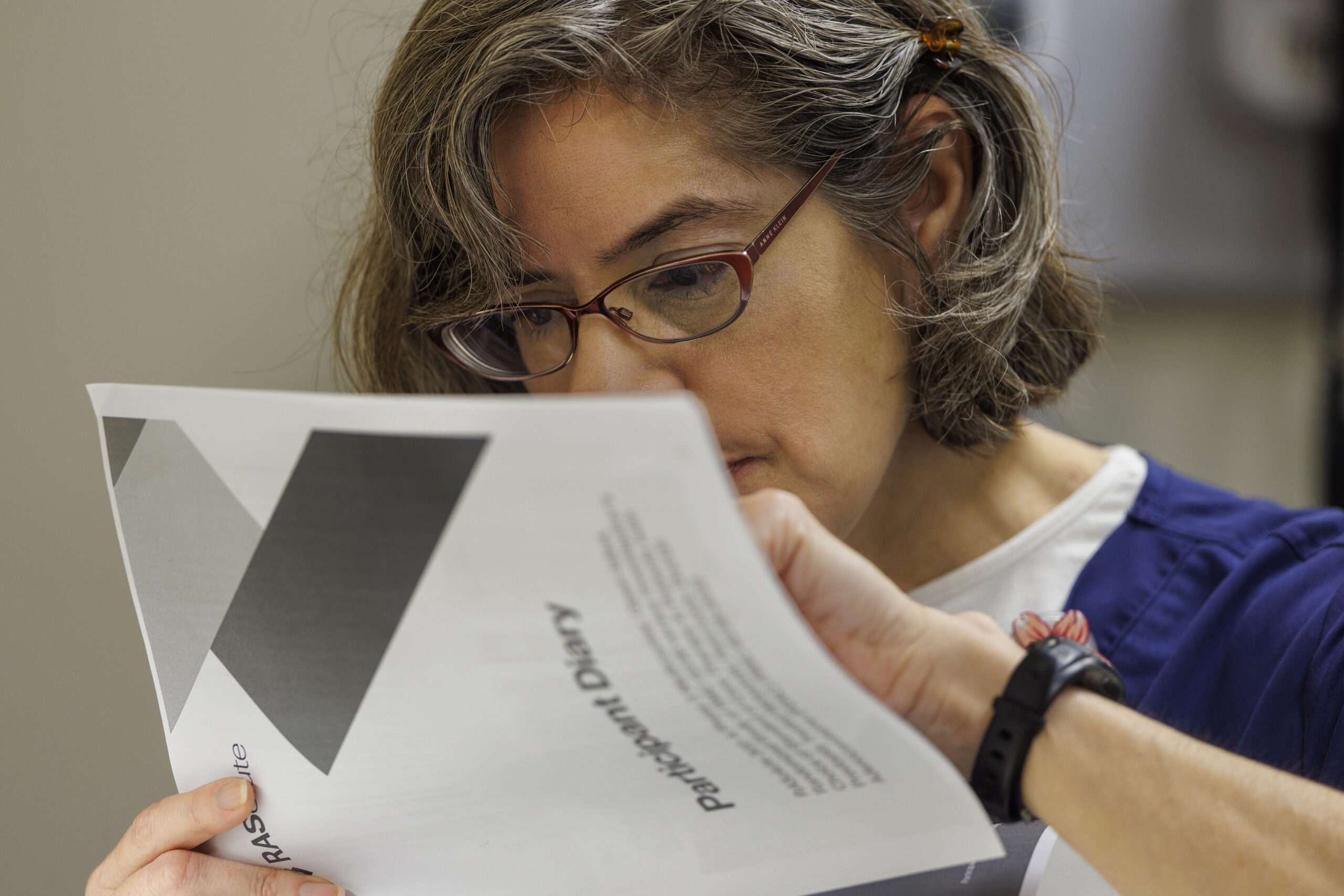

Payton, who owns a hair salon, isn’t certain her grandmother will stay in Connecticut for good. She keeps a close watch in case she needs to bring Madison back to Massachusetts. She talks about the need for more resources often with clients who find themselves in similar situations. “A lot of us are navigating these new things for the first time, and we don’t even know what to do or how to do it,” Payton said. “We just put more on our plate than I think we need to.”

Still, she said, “it’s kind of like a no-brainer. That’s my grandmother.” As a mother of five, Payton said she tries to involve her children in her grandmother’s care in small ways, teaching them to “treasure her because this is something that is not the norm, having your great-grandmother in your presence.”