By 2019, after a decade of producing dozens of documentaries about Philadelphia history, the filmmakers at History Making Productions realized they had more than just the story of a city.

They had the story of America.

On Friday, the studio released its epic, new telling of that 400-year-old story: In Pursuit: Philadelphia and the Making of America. Directed by documentary filmmaker Andrew Ferrett and written by author and historian Nathaniel Popkin — and mixing modern footage with historical recreation and more than 600 on-camera interviews — the 10-episode series explores the history of America through the lens of Philadelphia, its birthplace.

Timed to coincide with the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence in 2026, known as the Semiquincentennial, the series provocatively grapples with urgent questions, like how did the American experiment actually unfold? And how can it endure?

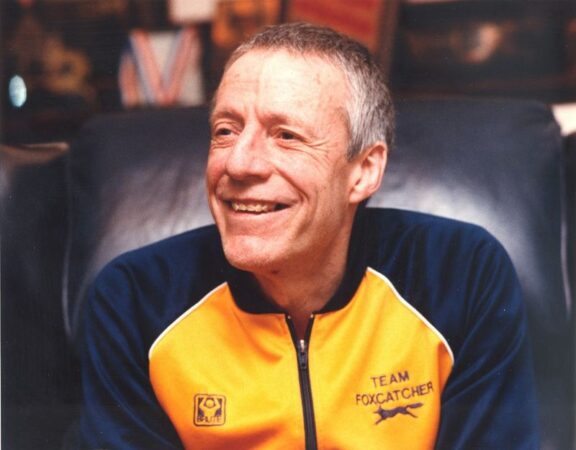

“Philadelphia is not just the birthplace of American democracy — it has been its proving ground,” said Sam Katz, series creator, executive producer, and founder of History Making Productions. “This series looks honestly at how ideals were formed, challenged, expanded, and sometimes betrayed, and why that history matters so urgently.”

‘A national moment’

Spanning 400 years of Philadelphia history, from its indigenous roots to the MOVE Bombing the series is equal parts entertainment and civic project. Funded by Katz and philanthropies like Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, Penn Medicine, and Lindy Communities, the series premiered at the National Constitution Center on Thursday.

Episode One is now streaming online. Katz and the filmmakers will host screenings and community conversations at Pennsbury Manor in Bucks County on Sunday, and another screening Feb. 26 at the Bok Building in South Philadelphia.

Throughout 2026, as the city and country celebrate the national milestone, a citywide “In Pursuit of History Film Festival” will promote each new installment with monthly screenings and public events. 6ABC will also air monthly hourlong shows to highlight new episodes.

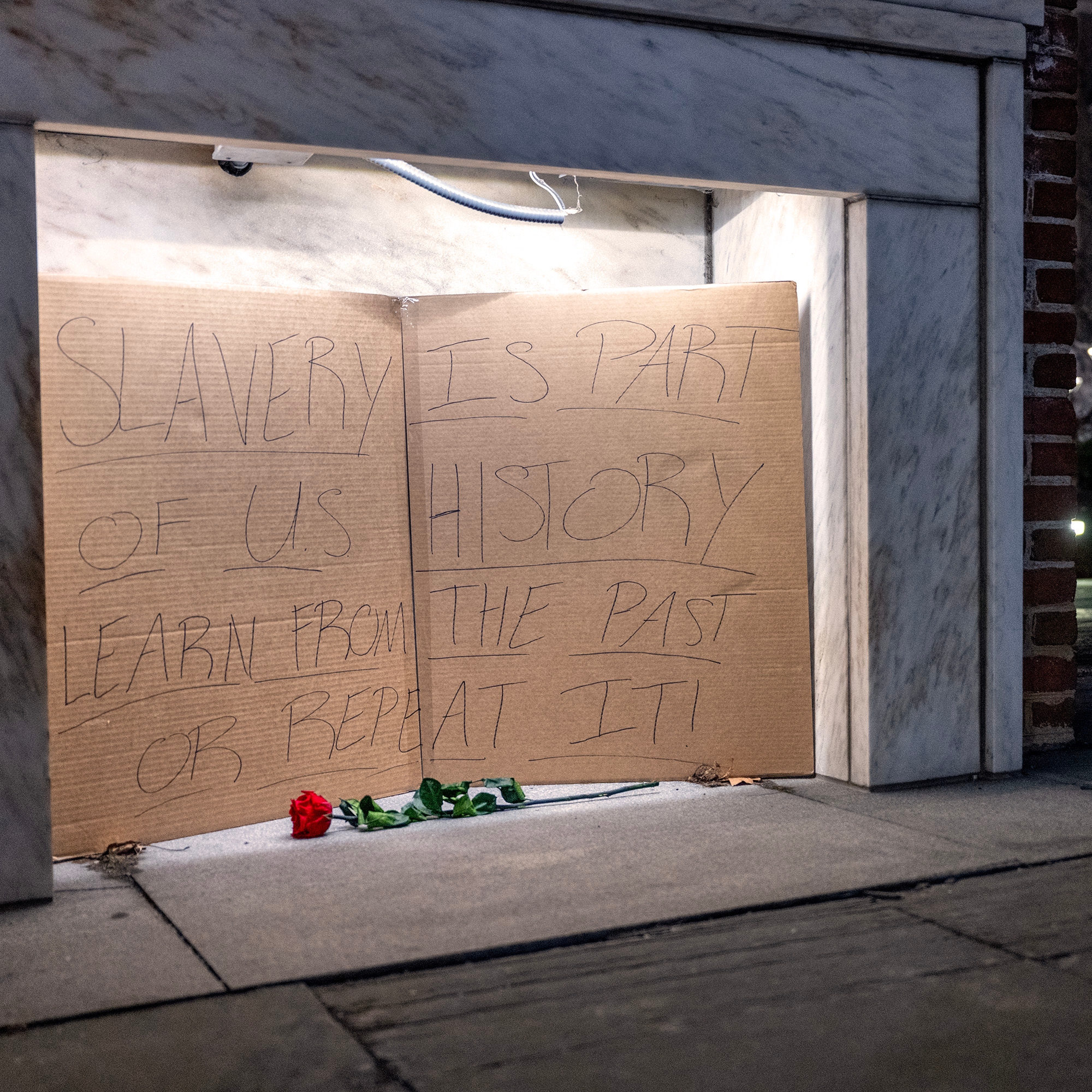

From the beginning, the project was meant to get people talking about the true meaning of the American experience, and those it has left behind.

“We’re going to get partners all over the city, and we’re going to have screenings all over the place,” said Katz, the civic-leader-turned-producer. “We’re going to create opportunities for people to come and meet the filmmakers, or meet a historian or an artist, who will then lead a conversation. It really is an opportunity for Philadelphia to take stock of itself.”

Popkin, who co-founded Hidden City Daily, said the project tells the story of events that shaped a city and a country founded on ideals not yet fully realized — and now divided and tested as they’ve been in decades.

“The timing is perfect,” he said. “I think a film can really launch a lot of conversations. This is a moment for us as a nation.”

Fresh portals

Ferrett, who grew up in Bucks County, and has been directing and producing films at History Making Productions for more than 15 years, said the project revealed itself.

For earlier Philly projects — including The Great Experiment, an Emmy-award winning, 14-part docuseries spanning 500 years of Philly history, and Urban Trinity: The Story of Catholic Philadelphia — the filmmakers had amassed hundreds of unused hours of interviews with local and national historians, artists, and cultural leaders.

Over the years, much of it had to be left on the cutting room floor, including magical moments that he said opened fresh portals to Philly history, said Ferrett.

“We talked to pretty much anyone you can imagine who was either involved with studying Philadelphia history, or in the case of 20th-century history, a lot of witnesses to it,” he said.

Besides, he said, nowhere else could hold a better mirror to America, than the place of its birth.

“It really became obvious to us that what we have here is much more than a local history,” he said. “It’s a history of the whole United States because so many consequential moments that shaped the country’s history went through Philadelphia.”

History that feels alive

Setting out to tell the story anew, Katz raised money to shoot updated interviews and fresh historical recreations.

Meanwhile, history did not slow down, from the COVID-19 pandemic, to the killing of George Floyd, and the Black Lives Matter movements, to Trump, and immigration crackdowns.

“We were asking how do we deal with history while all this is happening,” Katz said. “We were writing about it right now.”

Narrated in a warm, resonant baritone by actor Michael Boatman, known for roles in shows Spin City and The Good Wife, In Pursuit is no dull, black-and-white history. The city feels alive, the stakes serious and undecided.

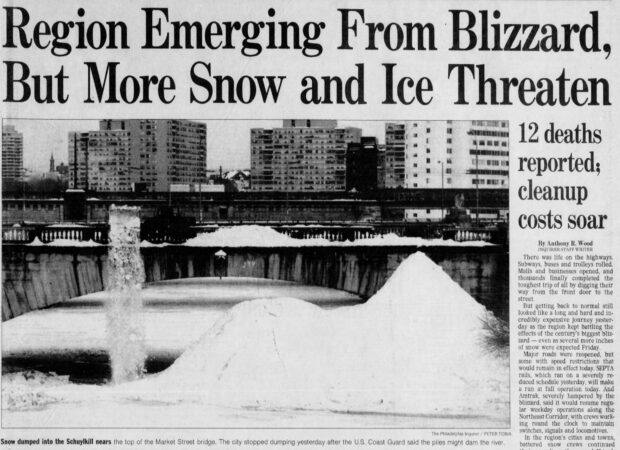

Threading modern day footage of bustling Philly streetscapes and soaring neighborhood shots with commentary and historical recreations imprints the series with a powerful immediacy.

The story stretches far beyond 1776, though the dramatic details of that sweltering summer in Philadelphia are recounted in episode three in gripping scenes of refreshingly believable historical recreations.

“We were able to shoot these lush and full reenactments,” said Ferrett, of all 10 episodes. “Sam was always like, ‘Where’s the dirt? I don’t want to see people with perfect teeth and smiling.’”

The start

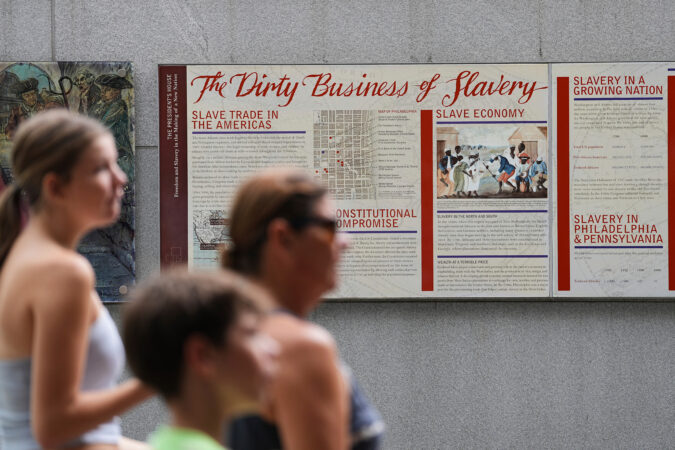

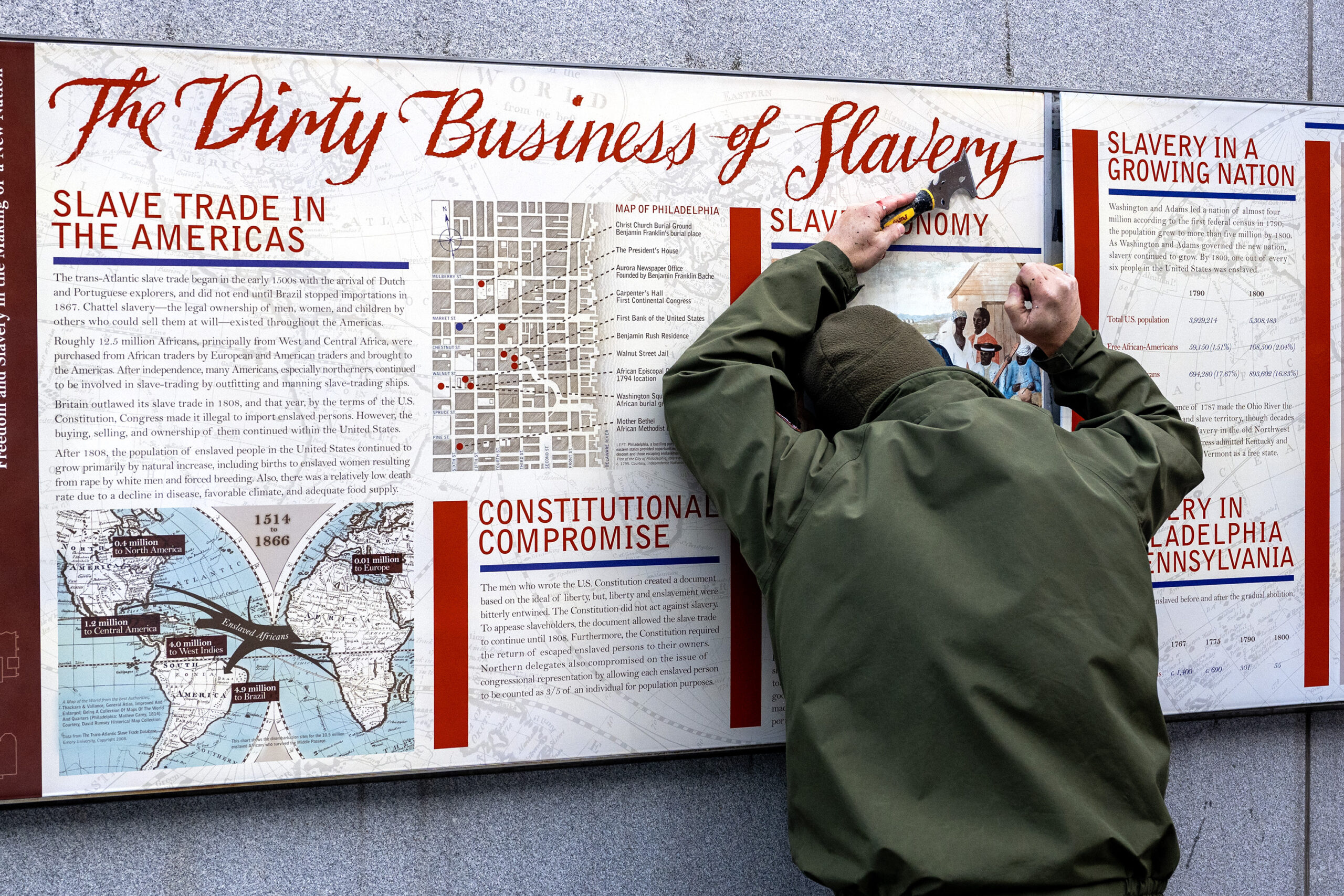

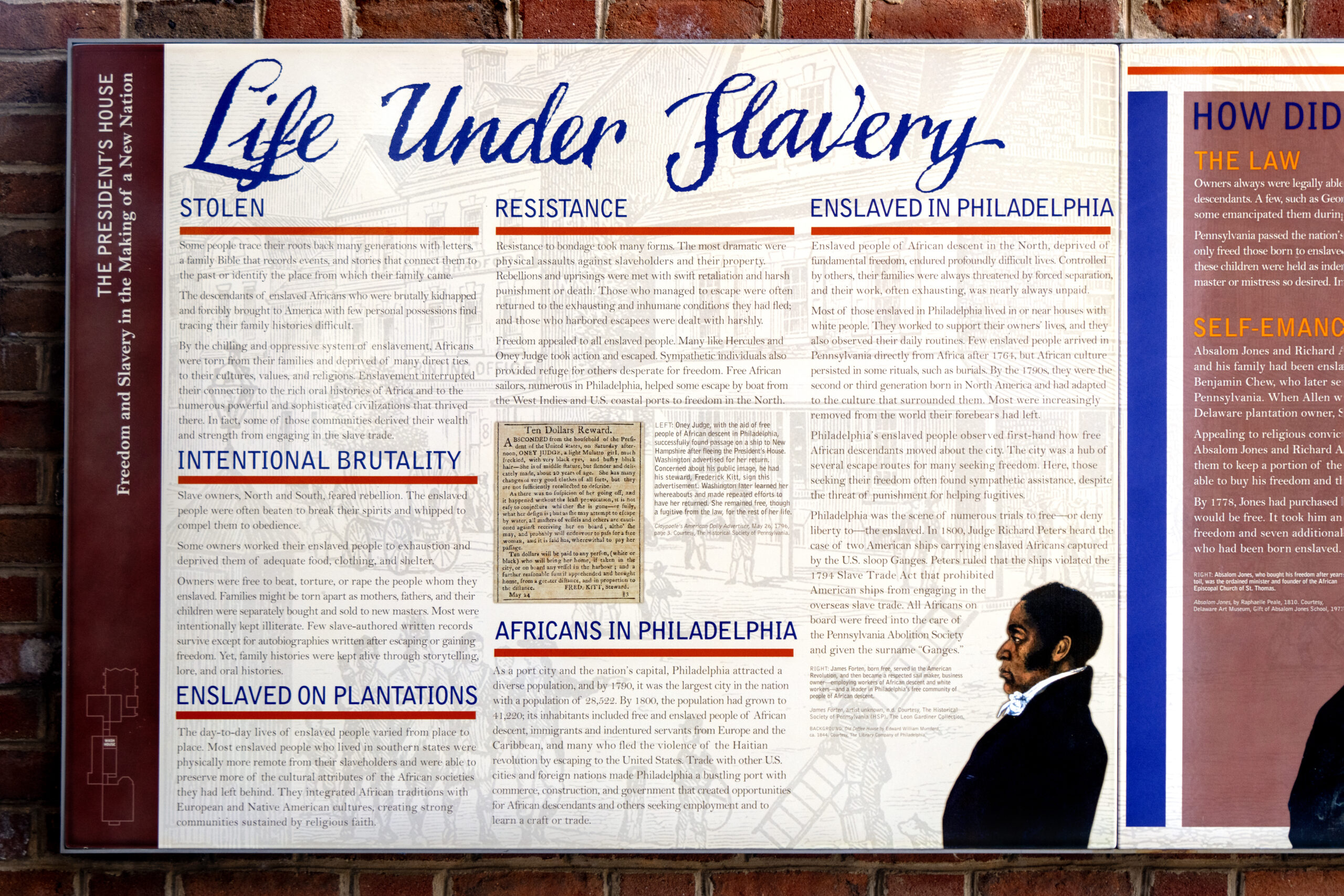

Episode One, “Freedom (to 1700),” begins at the beginning, pulling no punches as it tells the story of the Lenape people, Philadelphia’s earliest Indigenous settlers — and of the generations of Dutch and other European colonists’ efforts to eradicate them through violence and disease.

It surprises even in the telling of William Penn, recounting how the rebellious aristocrat’s non-conformist ways landed him in jail more than once, before he founded a City of Brotherly Love meant to be a better world, and a testing ground of the most advanced ideals in Europe.

The episode also showcases what Ferrett describes as “deepeners,” when the story cuts away from the arc of history for moments of reflection from modern Philly voices.

“We all feel it here … it’s all in our bloodstream,” poet Ursula Rucker says in the episode. “What does this city mean to me? Everything. Everything.”

–>

–>  –>

–>  –>

–>  –>

–>

–>

–>  –>

–>  –>

–>