Hi, Greater Media! 👋

Happy Thanksgiving! With one holiday here and several others fast approaching, we’ve rounded up over a dozen events you’ll want to add to your calendar. Also this week, the Delco-set HBO series Task will return for a second season, SEPTA is getting additional funding for Regional Rail car repairs, plus a gift guide with a very Philly twist.

If someone forwarded you this email, sign up for free here.

Over a dozen holiday events you won’t want to miss this season

The holiday season is officially upon us and with it, a slew of festive events. Whether you’re looking to snag a picture with Santa Claus or be dazzled by light displays, there’s no shortage of things to do in and around Media.

We’ve rounded up more than a dozen holiday festivities this season, including shopping pop-ups, holiday parades, cookie swaps, and more.

See the full list of holiday events here.

💡 Community News

- Trash and recycling pickups are operating on an altered schedule this week for the holiday. For more information on pickups, check the Media, Middletown Township, or Swarthmore websites, or for Nether Providence Township residents, check with your private trash collector.

- Heads up for drivers: Valley Road between Darlington and New Darlington Roads will be closed from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. next Wednesday through Friday for water main work.

- Good news for Task fans: The Delco-set HBO series has been picked up for a second season. The show has been awarded a record $49.8 million tax credit, the largest amount Pennsylvania has granted to a single production. While we don’t know when the crew will be back in town for filming or when the new season will debut, expect plenty more local scenes from creator and Berwyn native Brad Ingelsby.

- Gov. Josh Shapiro is sending $220 million to SEPTA, funds that will help the transit agency with repairs to its Regional Rail cars. Problems that arose while SEPTA inspected its Silverliner IV fleet caused a painstaking return to service and commuter delays. With the fresh capital, SEPTA aims to return service to normal capacity in the next few weeks.

- A pair of Swarthmore residents last week were accused of causing $130,000 in losses to a company after allegedly stealing and using corporate credit cards for their own purchases. They were arrested last week before being released on unsecured bail. (Patch)

- Swarthmore College will continue its test-optional admission policy for up to five more years as many schools continue to de-emphasize SAT or ACT scores in admissions decisions. (The Phoenix)

- Need a little help tackling your holiday gift list? We’ve put together a guide to over 70 very Philadelphia ideas, complete with a quiz to find the perfect one for yourself or your hard-to-shop for friends and family. Or check out columnist Stephanie Farr’s gift guide of the most Philly things around, including a Wawa snow globe.

- Speaking of shopping, 6abc recently visited Swarthmore thrift store Heart & Soul’d to chat with owners Terry Crossan and Kristen Mancini about their mission. The sisters’ shop, which sells an array of donated goods, helps benefit foster and adoptive services in the county, something close to their hearts given both have adopted daughters themselves. Watch the segment here.

- Those shopping in Swarthmore’s town center will get free parking on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays starting this weekend and running through the end of the year. In Media, the borough will have free daily parking at the Baltimore Avenue garage today through New Year’s Day.

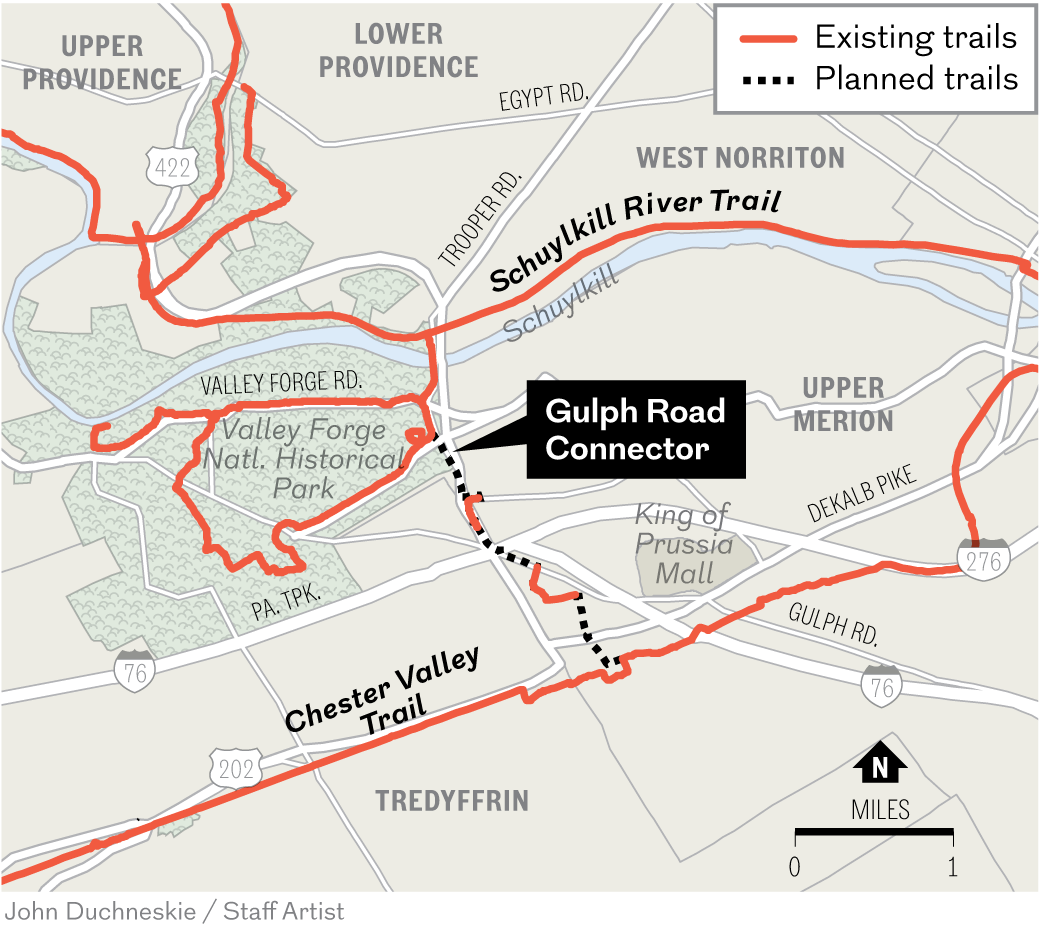

- Looking to avoid the crowds on Black Friday? Here’s a guide to some of the region’s walking and hiking trails.

🏫 Schools Briefing

- RTMSD is closed today and tomorrow for Thanksgiving.

- WSSD is closed today and tomorrow for Thanksgiving. Keystone testing dates begin Wednesday.

🍽️ On our Plate

- In case you missed it, Media is getting a new Mexican BYOB. Taquero features authentic dishes from around the country, including street foods and tacos, and is now planning to open on Monday.

- That’s not the only dining news in Media. Maris, a Mediterranean restaurant from Loïc Barnieu, has opened at the former Two Fourteen space on West State Street.

🎳 Things to Do

🎭 Annie: The Media Theatre kicks off its run of the beloved Broadway hit about an orphan who finds an unlikely champion in a billionaire. ⏰ Friday, Nov. 28-Sunday, Jan. 4, days and times vary 💵 $27-$47 📍 The Media Theatre

🎶 The Whitewalls: The nine-piece horn Philadelphia party band specializes in R&B, funk, pop, disco, and Top 40 tunes. ⏰ Saturday, Nov. 29, 8:30 p.m. 💵 Free 📍 Shere-e-Punjab

🏡 On the Market

A brick ranch with a three-season room

Built in 1957, this updated brick ranch offers single-floor living with a living room, dining room, kitchen, and four bedrooms all situated on the ground level. It also has an enclosed rear porch leading to a fenced backyard, where there’s an above-ground pool. There’s also a finished basement. There are open houses this Friday, Saturday, and Sunday from 1 to 3 p.m.

See more photos of the property here.

Price: $675,000 | Size: 3,300 SF | Acreage: 0.27

🗞️ What other Greater Media residents are reading this week:

- Trump accuses Democratic vets in Congress of sedition ‘punishable by death,’ including two lawmakers from Pa.

- Stephen Starr’s Borromini should be a showstopper. Instead, it’s a shrug.

- One of Philly’s most acclaimed bakeries has permanently closed

By submitting your written, visual, and/or audio contributions, you agree to The Inquirer’s Terms of Use, including the grant of rights in Section 10.

This suburban content is produced with support from the Leslie Miller and Richard Worley Foundation and The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Editorial content is created independently of the project donors. Gifts to support The Inquirer’s high-impact journalism can be made at inquirer.com/donate. A list of Lenfest Institute donors can be found at lenfestinstitute.org/supporters.