The bitter and persistent cold of recent weeks was so dangerous that various Philadelphia agencies coalesced around one mission: Get the city’s most vulnerable off the streets.

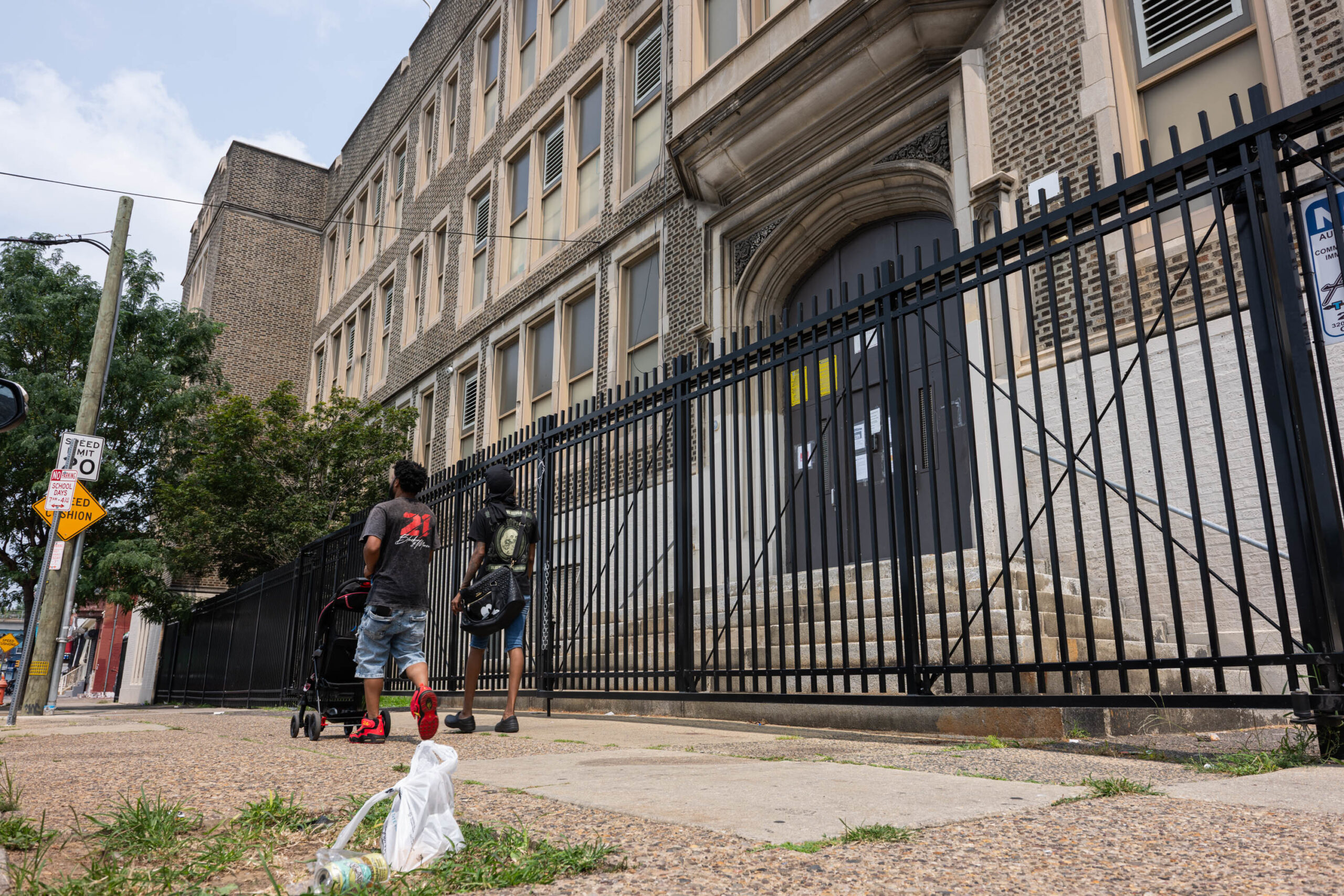

Philadelphia libraries became a key piece in these efforts, with some branches doubling as so-called warming centers for more than 20 days straight in an effort to provide a respite to people who would otherwise be living outside.

The mobilization of what can exceed 10 branches during life-threatening cold snaps is largely, though not universally, welcomed by library staff, the community groups that support the workers, and the people who use the spaces.

As outdoor deaths mount in places like New York City, where at least 18 people have died on the streets since Jan. 19, Philadelphia library workers see the initiative as a way to prevent similar outcomes here, where there have been three cold-related deaths since Jan. 20.

But employees say the warming center initiative, in only its second year as a formalized network, leaves branch staff, from librarians to security, unequipped to help some of the people walking through their doors with complex mental and physical health needs.

“People are feeling tired, feeling very burnt out, the physical, the emotional, and the mental load of not just doing our regular work, but having like this critical service, like lifesaving service, being offered on top of that for 12-plus hours a day has been really, really hard to sustain,” said Liz Gardner, a library worker, speaking as a union steward in the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees District Council 47’s Local 2186, which represents first-level supervisors, including those at libraries.

There’s the “little stuff,” like how an online map sometimes listed the wrong information in December. Last-minute location changes among the South Philly branches made it confusing for even the self-described information professionals to direct people where to go. At one point, a branch that was not Americans with Disabilities Act-accessible was cast as a warming center, to the chagrin of many.

Library workers and community groups described having to lobby the Free Library to crowdsource snacks and water. The transportation that transfers people to nighttime warming centers after the libraries close has often been late, meaning staff have to decide between staying after their shift or leaving people outside, which they don’t want to do.

What’s more, library workers and volunteers say, some people require more than a warm space. People in mental health crises, struggling with substance abuse issues, and requiring wound care need medical support, workers say.

“What [the city is] continuing to do is take advantage of a group of people that care so deeply about the city of Philadelphia and the communities that they serve, and they’ll continue to do it, regardless of if they have the support or not,” said Brett Bessler, business agent for DC 47 Local 2186.

Altogether, the concerns surrounding the warming center system yield existential and moral quandaries: Is this system the best and most humane way to treat some of the city’s most vulnerable people?

Crystal Yates-Gale, the city’s deputy managing director for health and human services, acknowledged some of the challenges described by library staff and volunteers. Many logistical issues, such as location changes, food, and transportation woes, were improving or had been resolved, she said. Some of the concerns regarding staffing might be a matter of miscommunication, she said.

“I think everybody’s exhausted. It’s like Groundhog Day,” Yates-Gale said. “It’s the same thing: Every day you wake up, they’re all just quite exhausted, but everybody’s working toward the same goal.”

Kelly Richards, president and director of the Free Library of Philadelphia, echoed the sentiment that staff have been saving lives. In a statement, he said he appreciated staff efforts and feedback as the Free Library continues “making improvements to better serve our communities.”

‘They need more than a warm building’

Details of who uses the warming centers are limited. Visitors are not asked if they are at a library to escape the cold or for regular library programming.

Three library workers from various corners of the city described some of the daily challenges they have faced at warming centers to The Inquirer under the condition that they remain anonymous, fearing professional repercussions.

One worker who has lived through various iterations of heating and cooling operations involving libraries described a catatonic man being brought into their branch by first responders, left for staff to figure out his care.

“They need more than a warm building,” the worker said. “These are human beings, and we’re the wrong department to help.”

A worker at a different branch described trying to persuade a man with a festering wound to seek medical intervention. In another instance, when staff told a man he could not set up his sleeping bag on the library floor, he began shouting, telling workers they had to accommodate him.

Library staff say one of the biggest challenges is the lack of consistent support for people with complex medical issues.

Yates-Gale said the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services staff focuses support on what are considered “high-volume” warming centers, including the Central Library and the Northeast Regional and Nicetown branches. Mobile teams are available by request.

In other cases, through a partnership with Project HOME, the city’s homeless services office assigns what is called a restroom attendant.

Library workers and volunteers say the current setup is unfair to all involved.

At the South Philadelphia Library on a recent Friday afternoon, a woman yelped in pain as she rubbed a blackened, possibly frostbitten toe. Children played with blocks in a corner as others checked out books.

Library staffers maintain similar scenes have played out at the various warming centers, with workers left to balance the comfort and safety of people there to check out books and use their computers with those of people who might die if kicked out and sent to the streets.

The worker who told of trying to persuade a man to seek medical attention noted that staffers are behind on work and programming has taken a hit.

Kelsey Leon, a harm reductionist who regularly works with homeless Philadelphians with addiction, has been visiting libraries during the cold snap after hearing concerns from librarians, and working to deliver wound care kits to the centers so people there can treat themselves.

Librarians “are so clearly beyond their capacity to handle this,” she said.

The city says it’s listening to feedback

A battle for snacks, workers and volunteers say, has become emblematic of the disconnect between what the Free Library and the city want warming centers to be and what they actually are.

Most people using the service do not bring their own food.

The city initially provided snacks at the overnight warming centers in recreation centers but made no such offerings at the daytime ones at libraries.

When staff and volunteers noted this would mean people going 12 hours without sustenance and offered to fill that gap with crowdsourced snacks and drinks, they faced resistance.

“We were told repeatedly that warming centers at libraries are distinct from shelters, and that is the reason they couldn’t provide food,” said a third library worker, adding the Free Library and the city eventually allowed the outside snacks to come in.

Part of the initial hesitation, according to Yates-Gale, was based on logistical considerations, including protecting library materials and adding cleanup to the plate of security officers who handle maintenance.

The city provided library leadership with lists of food sites, the idea being that people could leave the libraries, get a meal close by, and come back.

Still, Yates-Gale said, the city is listening and adjusting in real time.

Last week, after two weeks of operations, the city brought water and cereal to warming centers. The city says people also have access to water fountains.

The city said it is not giving up on improving warming center conditions. Yates-Gale said that starting Tuesday, the Philadelphia Office of Homeless Services would send reinforcement teams to daytime warming centers to get people to connect to additional services.

The backup cannot come fast enough.

Ibrahim Banch, 26, has been homeless before, but the cold he has experienced recently is something different.

“The air feels solid. It stands your hair up,” he said. He knew he couldn’t stay outside, so he sought out the warming centers as temperatures dropped. Recently released from prison, he said, he is waiting to be placed in an emergency shelter bed. But the warming centers are a last resort.

He said the city should staff all centers with workers equipped to deal with the mental health needs that many clients have.

“People at the library shouldn’t have to take this responsibility,” Banch said. “It’s not a shelter or a caregiving place.”

Volunteers still eager to help

Erme Maula, with the Friends of Whitman Library in South Philadelphia, echoed the challenging conditions described by workers. She believes it doesn’t have to be this way.

The city’s 54 branches are full of supporters who can coalesce around the warming centers with donations, she said. Volunteers continue to collect toiletries and other essential items for people using the branches for warmth.

As an advanced practice community health nurse, she could see healthcare workers organizing to help people and ease the load of librarians. But it is the sort of effort that would need support from the city.

“People are kind and want to be generous, but they didn’t know you have to take care of what they expected the city to be able to take care of,” Maula said.

Maula and others who spoke to The Inquirer emphasized they want the warming centers to be improved — not to go away.

As with the snack issue, Yates-Gale said the city is responding to feedback in real time.

“Now that we know that there needs to be an adjustment for support staff, we’re ready and able to immediately begin staffing the libraries,” she said.

But that might not be felt by library staff until the next warming center activation. With daytime temperatures finally warming up, the city is slated to begin winding down warming center operations at libraries; nighttime centers will remain open until those temperatures similarly rise.

“I’m really hopeful that we see substantial improvements to make this a more sustainable practice that helps more people in a more meaningful way,” Local 2186’s Gardner said.